All stories end in death if you want to tell the truth.–David Simon

All stories end in death if you want to tell the truth.–David Simon

I’m afraid of endings, always have been. I am not alone in this fear, of course; many of us fear endings. Not just death but departures, demises, denouements–the invariable deflation of crossing a finish line. But my fear is acute, to the point that I privately view success as dangerous, possibly even fatal, because it will end life as I know it. (Glamourously underachieving is pretty core to my current existence.)

I’ve had so much time to acknowledge this fear since last month’s hunter’s full moon, which was the night my back went out. A catalog of the reasons why it did: loose joints; a rigorous, not entirely mindful exercise practice; shame about my middle-aged midriff; the 10-year anniversary of an acute neck and back injury.

All those contributing factors are real. But if there weren’t a deeper reason, I think I’d be better by now. After all, my list of treatments reads like a 1970s self-help saga: I’ve done acupuncture, astrological readings, Alexander Technique, reiki, physical therapy, and so many herbs and homeopathics. (I”m not really a painkiller girl except for the occasional whiskey.) I’ve meditated, prayed, danced under the light of the (next) full moon. And it’s all helped.

But though I’ve improved– can walk a few miles, tote my laundry (though I probably shouldn’t)– the pain and stiffness malingers.

Understand I’m already gentler because of this pain. Already moving with more heart and less harshness toward myself and others.

And the reactivation of my loving-kindness is a huge boon. Because for years I’ve been aware of others’ pain without allowing myself to worry about it. Don’t get me wrong: Radical empathy requires significant boundaries lest I be walloped by others’ emotional baggage, which is especially heavy when they don’t acknowledge it.

Most people only touch base with their truest selves when they’re hurtling between destinations. I see it on the NYC subways, when passengers put down their phones and settle into their real feelings–disappointment, rage, fear, and, yes, love. Once upon a time, I felt so inundated by all that emotional energy that I only could ride a subway once a day lest I drain my battery entirely.

Eventually I learned to erect psychic shields–establishing a formal intuitive practice helped me do so–and these days travel in relative peace, clocking the parade without being felled by its sis-boom-bahs.

But this calcifying back injury has revealed that, somewhere along the (subway) line, I stopped feeling invested.

It’s an occupational hazard, I suppose. When you observe the whole freaking timeline of any given person’s life, everything smoothes into one endless horizon. You start to recognize death as part and parcel with life, joy as part and parcel with sorrow.

But ultimately that kairos consciousness precludes being fully present. It’s beautiful but also bullshit. You stop fearing anything because you stop feeling anything.

Now I am present as can be, because pain has a way of yanking you into the moment. It’s hard to dissociate while an electrical current shoots throughout the right side of the body– sometimes into the jaw, sometimes down to the big toe.

Of course it’s the yin side, the proactivity side. The get-your-ladybuns-in-the-air side.

Yes, anatomically this pain emanates from a pinched nerve. But more and more I grok that it’s no coincidence where that nerve is pinched. I sing the body electric, because we’re all energy as well as matter. No either/or in this equation of living as incarnated spirit.

Anyway. I know I am leaning hard into the downside of dowager chic by delving so deeply into my middle-aged maladies, but I’ve always written about whatever progresses the soul, and this time (and so many others) it’s about pain as alarm clock.

I’ll leave you with this. In all my decades of exploring healing modalities I never tried craniosacral therapy until yesterday, when I met with J, a specialist recommended by Leslie, my brilliant Pivot Fitness ally. When I walked into J’s sweetly stuffy Union Square office, I immediately registered that too-elusive home feeling, what I call the “there you are!” zing the first time you meet someone who already makes sense.

It wasn’t just that I recognized her as another survivor of downtown 90s NYC bohemia. It was that I could tell she actually saw me–not just my red-lipsticked, high-low mix of dirty and deep, but the empathy, loneliness, and industriousness that only my closest friends know well.

“Let’s get you on the table,” she said, cutting through my chatter immediately. Then, though I’d told her nothing about myself, she laid her hands right where it hurt most and said, “What’s the plan with your book?”

I sat straight up, because she’d gotten to the heart of it within five minutes.

What’s the plan with your book?

“Why?” I said defensively though I knew she’d been guided to ask by the same divine forces that prompted me to write a book in the first place.

Gliding her hand to my heart chakra, she said, “It’s okay to answer.” And I burst into horrible, hacking tears,

“I have no fucking clue,” I said.

Lifting her hand lightly, she said, “My sense is this pain will subside as you write toward the finish line. I keep hearing the phrase, ‘Endings are important and they’re not going to kill you.’”

The freaked-out teenager I carry is not convinced she’s right. Writing my way through the dread and sorrow and fear I felt in 1989– the year I graduated from high school, the year in which I’ve been professionally stuck for six months–does feel like it’s going to kill me. But if my back pain has taught me anything, it’s that not feeling (and not writing through that feeling) also might be the death of me. I may never be fully present again until I confront my fears and rage from that past. But I’m glad to care again. It’s so much worse not to care.

Which seems as good a place as any to end this first post in a dog’s age.

Endings are important and they’re not going to kill you.

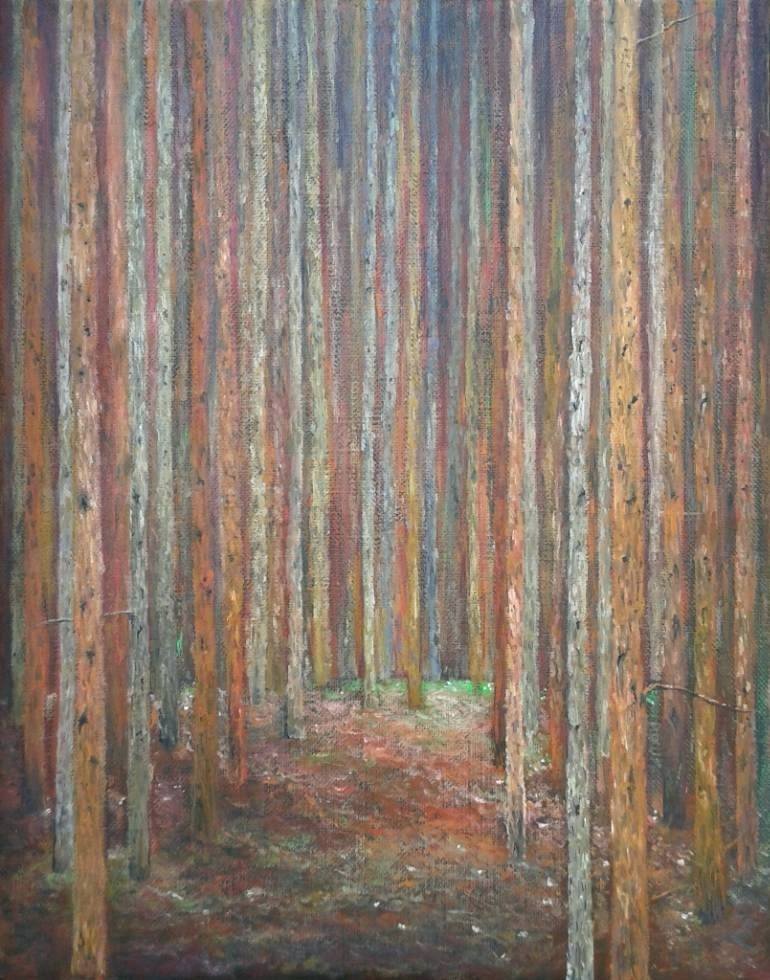

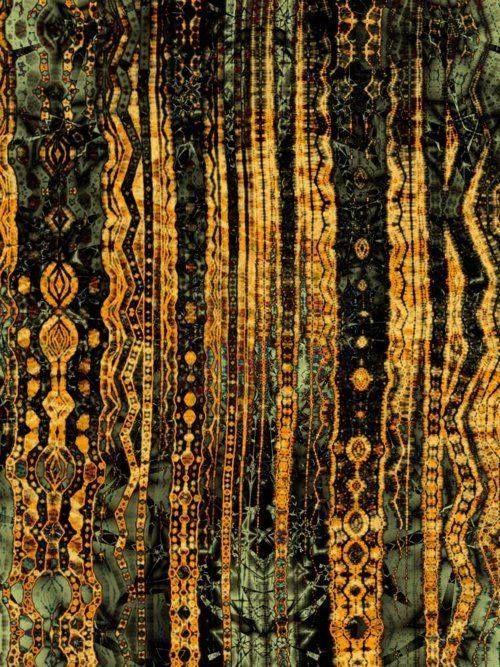

Art: Gustav Klimt