Without a doubt, this is the Summer of Amy Schumer. Her Comedy Central show lights up social media feeds like a Christmas tree every week, her speeches are the stuff of which female empowerment dreams are made, and her tweets are analyzed as if they were the National Debt. Now, with “Trainwreck,” she’s starring in a Judd Apatow-directed feature film that she also wrote, at least partly based on her own experiences.

Without a doubt, this is the Summer of Amy Schumer. Her Comedy Central show lights up social media feeds like a Christmas tree every week, her speeches are the stuff of which female empowerment dreams are made, and her tweets are analyzed as if they were the National Debt. Now, with “Trainwreck,” she’s starring in a Judd Apatow-directed feature film that she also wrote, at least partly based on her own experiences.

Case in point: thirtysomething New Yorker Amy stars as thirtysomething New Yorker Amy, though she is a writer for a Maxim-style magazine rather than a stand-up comic. The film begins as her father, played by the perpetually indignant Colin Quinn, is explaining to his tweens Amy and Kim why he’s divorcing their mother: “Repeat after me, girls: Monogamy is unrealistic.” Cut to a present-day montage in which obedient daughter Amy behaves promiscuously, gets wasted, and wakes up in a stranger’s bed in Staten Island. On her ferry ride of shame, clad in a gold micro-mini, she splays her arms at the bow of the ship in the wannest of homages to “The Titanic.” Roll the opening credits!

It’s a brilliant beginning – everything we’d hope for in Schumer’s first feature – and if the rest of this film followed suit, she’d be king of the world. But while “Trainwreck” is hardly true to its title, it suffers from an identity crisis that dulls the acuity that makes the comedian the toast of water coolers everywhere. Chalk it up to an uneasy marriage between Schumer’s glass-ceiling-shattering riffs, which may be best suited to stand-up and short skits, and the “Apatow Agenda” – that is, family values delivered via boot shoot.

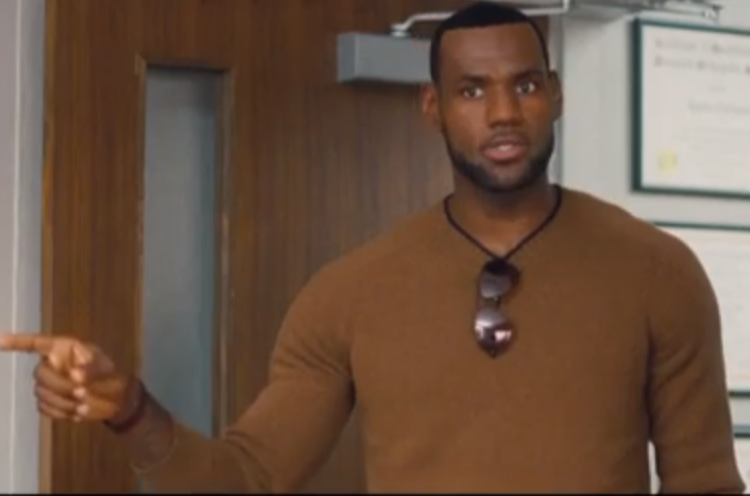

This is not to suggest there aren’t wickedly funny bits galore. A true daddy’s girl, Amy has the libido and dating ethics of your basic frat boy, and she and Apatow glory in exploring the attendant comic possibilities. A scene in which a meathead trainer (wrestler John Cena, really giving it his all) attempts to talk dirty is one for the ages. “I’m going to fill you with protein! Betacarotene!” he barks while Amy shifts uncomfortably beneath him. In general, the supporting cast is this film’s greatest strength, especially Tilda Swinton, barely recognizable in a maelstrom of bronzer and brass balls as Amy’s editor, and LeBron James as a tightwad, gleefully earnest version of himself. (Is there anything LeBron can’t do?) Only the great Brie Larson, playing Debbie Downer sister Kim, is seriously underutilized though scenes with her sap husband (Mike Birbiglia) and stepson (Evan Brinkman) are sweet.

This is not to suggest there aren’t wickedly funny bits galore. A true daddy’s girl, Amy has the libido and dating ethics of your basic frat boy, and she and Apatow glory in exploring the attendant comic possibilities. A scene in which a meathead trainer (wrestler John Cena, really giving it his all) attempts to talk dirty is one for the ages. “I’m going to fill you with protein! Betacarotene!” he barks while Amy shifts uncomfortably beneath him. In general, the supporting cast is this film’s greatest strength, especially Tilda Swinton, barely recognizable in a maelstrom of bronzer and brass balls as Amy’s editor, and LeBron James as a tightwad, gleefully earnest version of himself. (Is there anything LeBron can’t do?) Only the great Brie Larson, playing Debbie Downer sister Kim, is seriously underutilized though scenes with her sap husband (Mike Birbiglia) and stepson (Evan Brinkman) are sweet.

Apatow is too good a feminist to constrain Amy to a straight-up “taming of the shrew” plot – he consistently upholds strong women on- and off-screen – but his conventionality certainly reins her in. Amy gets assigned a profile on star sports doctor Aaron (Bill Hader, bridging the gap between his SNL comic chops and the gravitas he introduced in last year’s “The Skeleton Twins”), and they commence a relationship despite how uniquely ill-equipped she is for romantic lerve; she even heckles her own “Manhattan”-inflected falling-in-love montage in a truly inspired voiceover. Insert real life, including a subplot in which Amy and Kim negotiate the care of their alcoholic, MS-afflicted father (Apatow is that rare Hollywood helmer who acknowledges class and money issues) and an inevitable if too-perfunctory self-reckoning. (The climactic scene is cringe-worthy.)

But it’s too easy to assign all the party-pooping to Apatow. It is true that, while he is unparalleled as a producer and general curator of talent, his directorial efforts tend to be big-hearted shaggy dogs that fall apart due to an excess of moralizing. “Trainwreck” lags near the end, and its depiction of current-day New York is an unfortunate throwback to the 1990s playground of his youth; what young hipsters voluntarily go drinking in the West 30s and never visit Brooklyn these days? (Ditto for the ultra-’90s take on the media; if you want to take us down, you’ll need to hone your sword, sir.) Still, this is his most shapely and least sitcommy film – partly because he’s working with DP Jody Lee Lipes (“Tiny Furniture,” “Martha Marcy May Marlene”), and partly because Schumer herself wrote the script. Despite the fact that she’s everyone’s darling, though, Schumer herself is a problem.

But it’s too easy to assign all the party-pooping to Apatow. It is true that, while he is unparalleled as a producer and general curator of talent, his directorial efforts tend to be big-hearted shaggy dogs that fall apart due to an excess of moralizing. “Trainwreck” lags near the end, and its depiction of current-day New York is an unfortunate throwback to the 1990s playground of his youth; what young hipsters voluntarily go drinking in the West 30s and never visit Brooklyn these days? (Ditto for the ultra-’90s take on the media; if you want to take us down, you’ll need to hone your sword, sir.) Still, this is his most shapely and least sitcommy film – partly because he’s working with DP Jody Lee Lipes (“Tiny Furniture,” “Martha Marcy May Marlene”), and partly because Schumer herself wrote the script. Despite the fact that she’s everyone’s darling, though, Schumer herself is a problem.

Until now, she’s made her name in stand-up and skit comedy, and both formats are all about the quick punch, about “killing it.” The format of a feature-length narrative requires that she deepen her game and connect with others, and she doesn’t seem entirely up to the task. I don’t buy her love for her sister, and I don’t buy her chemistry with Hader (which is crazy; the man is dreamy). To some degree, that’s the nature of the character, but the consistency and extremity of her disconnect defies the dramatic requirements of the plot. The only person Amy really connects with is Quinn. With their pugnacious manner and features, the two are cut-ups from the same cloth, and their riffing is sheer delight. But Amy only seems comfortable when she’s riffing; all her lines sound like stand-up. This is directly contrary to what’s best about Apatow’s films; he’s willing to hang in there until the humor of a scenario develops naturally. Because she never really acknowledges the humanity of others in her shtick, Amy starts to feel two-dimensional after two-plus hours, except in one remarkably affecting scene. (To reveal its contents would be a spoiler.)

Here I must confess I’ve never wholeheartedly been on the Schumer train – wreck or not. I appreciate her contributions to our cultural lexicon and that she is using her “mean-girl humor” to lampoon sexism. But though she may be a bully batting for the right team, she’s a bully nonetheless. Much has been made of the way political correctness hampers stand-up comics but I say the best  comedy has always been used to subvert the status quo rather than reinforce it. In her stand-up and in her sometimes-questionable plays on race (in this film and elsewhere), Schumer perpetuates the mistakes of so many cultural rebels that have come before her; she tackles the issue that matters to her (sexism) while otherwise falling back on stereotypes and oppositional humor. To be fair, she recently has thrown some mea culpas into the ring. But her spirit of “us versus them” (even if it’s herself she’s battling; I’m sick of Spanx jokes) – of going for the jugular rather than teasing out nuances – remains. Ultimately this may not be best suited to feature-length films, especially when attached to Apatow’s oddball sermonizing. “Trainwreck” still brings plenty of laughs. But having your cake and eating it too may not be the most delicious of renegade humor – at least when served up with our popcorn.

comedy has always been used to subvert the status quo rather than reinforce it. In her stand-up and in her sometimes-questionable plays on race (in this film and elsewhere), Schumer perpetuates the mistakes of so many cultural rebels that have come before her; she tackles the issue that matters to her (sexism) while otherwise falling back on stereotypes and oppositional humor. To be fair, she recently has thrown some mea culpas into the ring. But her spirit of “us versus them” (even if it’s herself she’s battling; I’m sick of Spanx jokes) – of going for the jugular rather than teasing out nuances – remains. Ultimately this may not be best suited to feature-length films, especially when attached to Apatow’s oddball sermonizing. “Trainwreck” still brings plenty of laughs. But having your cake and eating it too may not be the most delicious of renegade humor – at least when served up with our popcorn.

This was originally published in Word and Film.