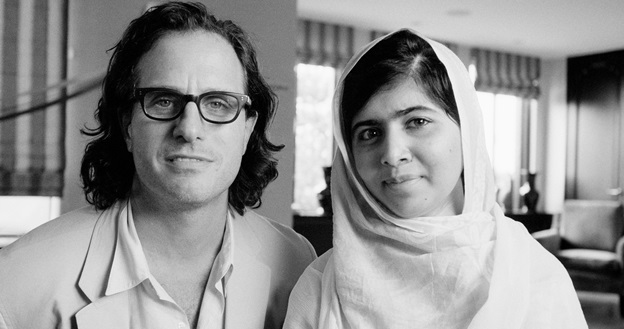

“Just because she has become a P.R. machine doesn’t mean she’s not the real deal,” said director Davis Guggenheim of Malala Yousafzai, the eighteen-year-old education activist who was shot in the head in 2012 and lived to tell her story. We were at New York’s The London hotel, where, along with producers Laurie MacDonald and Walter Parkes, Guggenheim had convened to discuss “He Named Me Malala,” their documentary about the Pakistani teenager who had become a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, opening October 2. At times, the conversation, though polite, became quite charged.

Because he was in a room of mostly American journalists, one of the first questions lobbed at Guggenheim was, “How, as filmmakers, did you navigate the fact that Malala has become a brand?”

“I understand why you have to ask that,” said Guggenheim, with a professorial patience. “But I live in a very nice Hollywood ghetto and my process is to make the stories I want to make, which is very separate from brand-making.” (Among the director’s previous projects is the Academy Award-winning eco-documentary “An Inconvenient Truth.”)

MacDonald said, “When we first met the Yousafzai family, they had just moved to Birmingham from Pakistan and were refugees of sort. She is so well known now but there’s none of that around her, especially where she lives. She was, as she is now, primarily concerned with getting to do her schoolwork. She bonded most with other girls in the world who were being denied an education.”

Although the director and producers said they “very much admired” Yousafzai’s memoir, I Am Malala: The Story of the Girl Who Stood Up for Education and was Shot by the Taliban, they were quick to establish they’d decided to make this documentary long before the book had become a bestseller. “Laurie and I read Malala’s twelve-page book proposal, and immediately saw the cinematic elements,” said Parkes. “That she was named by her father for a martyr in the wars between Pakistan and England suggested there was a destiny involved that had been put in place. What’s the responsibility associated with that? Right away this triggered a sort of excitement in us about hidden thematic elements that, if we did our job correctly, we could bring to light in a way that news organizations could not.”

“When making a film, I usually invoke the Hippocratic Oath,” continued Parkes. “I say, ‘We don’t have to make the world a better place. Just do no harm.’ But every once in a while you can make a movie that may make a positive change, by helping people know Islam better, for one thing.”

“There’s a part of telling Malala’s story that’s about depicting a real, non-fundamentalist Muslim family that is not demonized in the Western press,” agreed Guggenheim.

“But what about the fact that a large population of Pakistan regards her as a puppet of Western culture?” somebody murmured.

“Look, we get it,” said MacDonald. “The equivalent would be if the only story coming out about America was a racial incident. But there’s something about the age Malala was at, and the miracle of her surviving a gunshot to the head only to become even more fearless, more determined to be a leader, more articulate, that captured the world’s attention. She still takes risks by being out there but her cause is clear and there’s not a P.R. machine around that could tell her to behave otherwise.”

“They were an ordinary family living in the Swat Valley [the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of northwest Pakistan, where the local Taliban had banned girls from attending school] and something very precious was taken from them,” said Parkes. “To our Western lens their level of international recognition may make them suspicious since everything here is about getting something for yourself. But for the Yousafzais, telling their story was not natural for them. It was part of their survival and of bringing help to that part of the world, and to other girls in the world who are being denied education.”

“We showed her and her family our rough cut,” he continued. “And they had feedback about how we had portrayed Islam, errors that displayed unconscious biases, like when we did and did not translate the word ‘Allah’ to ‘God.’ We went back in and did our work, and then they were happy with the cut. Enough that Malala’s mother said she wanted to be included in the film, though she’d been taught to perceive appearing on camera as immodest.”

Guggenheim said that he kept “Grizzly Man,” Werner Herzog’s documentary about an idealistic animal rights activist who was killed by a grizzly bear, in mind while making this documentary. “It balanced light and dark elements very effectively, which is something I knew I had to do to reach viewers.” He also referenced the films “Persepolis” and “Wadjda,” both about female tweens navigating Islamic culture, which he said would provide excellent “double feature” viewing material with “Malala.”

Asked why he’d used animation to tell part of this story, the director said, “When I make a movie, I have a specific audience in mind. I made ‘Inconvenient Truth’ for my Republican cousins in Ohio because I really didn’t want to make a movie for people who already were convinced. With this movie, I had my fourteen-year-old daughter in mind. I wanted to visually portray the very childlike personal confessions that Malala shared in early audio interviews so we could capture her humanity. I knew if this film got too heavy into the geopolitics of the issue – issues that Malala covered very well in her book – I might lose my target audience. I wanted my daughter to see this and make her say, ‘If push comes to shove, I also will raise my voice and speak out.'”

This was originally published in Word and Film.