Last weekend I went to Philadelphia for the first time in nearly twenty years. Just writing that sentence fills me with awe. Apparently when you live long enough, you become your own personal time machine.

Last weekend I went to Philadelphia for the first time in nearly twenty years. Just writing that sentence fills me with awe. Apparently when you live long enough, you become your own personal time machine.

It was a good visit if discombulating, especially since I made the trek without my dearly departed auto Sadie. I went to college on Philadelphia’s Main Line and, though I grew fond enough of the city, I never liked my alma mater or Pennsylvania overall. Over the years I stopped going back, venturing instead to other parts of the world on the occasions that I left Brooklyn.

This time I took Amtrak, which I enjoyed once I adjusted to the lack of privacy. It reduced the travel to a glamorous ninety minutes door to door, and afforded me the luxury of intermittently dozing and ogling the scenery. But something about going without my wheels to the place where I began my adulthood felt stark. Every time I turned a corner, I expected to run into stricken nineteen-year-old Lisa, bristling with unharnessed hormones and newly discovered anger and fear. It was a pleasure to offer that ghost assurances that I’d become some of what she’d hoped to be. It was a pleasure to catch up with friends over gorgeous meals and music.

On the way back to New York, my train was halted, and it reminded me of my move to Brooklyn from Pennsylvania decades before. If you have short pockets and all the patience in the world, you can take commuter rails the entire way between the two cities. It’s something I did constantly in the summer after college, when I’d perched in a professor’s house and shuttled to NYC for job interviews.

Right before the weather had gotten crisp, I’d finally found a gig.  It was a dreadful one; I’d been hired as the assistant to a famous book publisher who was notorious for being the first woman to hold such a position and for hating other women. Even in our initial meeting, I could sense what a trial person this person would be. (Her current assistant had nervously lit her another cigarette before she’d finished her first one.) But this beggar couldn’t be choosy. I didn’t even have the money to rent a place for the first few months I’d have the job, so I arranged a couch-surfing schedule and brought only a knapsack to minimize my carbon imprint while on others’ turf.

It was a dreadful one; I’d been hired as the assistant to a famous book publisher who was notorious for being the first woman to hold such a position and for hating other women. Even in our initial meeting, I could sense what a trial person this person would be. (Her current assistant had nervously lit her another cigarette before she’d finished her first one.) But this beggar couldn’t be choosy. I didn’t even have the money to rent a place for the first few months I’d have the job, so I arranged a couch-surfing schedule and brought only a knapsack to minimize my carbon imprint while on others’ turf.

At 5 am of my first day, I packed my most precious possessions, put on nylons (in the ’90s, office girls were still expected to encase their legs in skin-colored plastic), and embarked on the slow, smelly trip between the two cities. Upon arriving in Manhattan, I’d jumped on a subway, which, en route to my eastside office, had screeched to a stop. A woman had thrown herself on the third rail and succeeded in killing herself.

I sat on the traincar and clutched my bag, trembling. Was it a sign? I knew no one well in this vast and terrifying city. I had no cash. I had no Plan B if things went awry. Would I ever find my niche? Or would the city claim my sanity as she seemed to have claimed this poor soul’s?

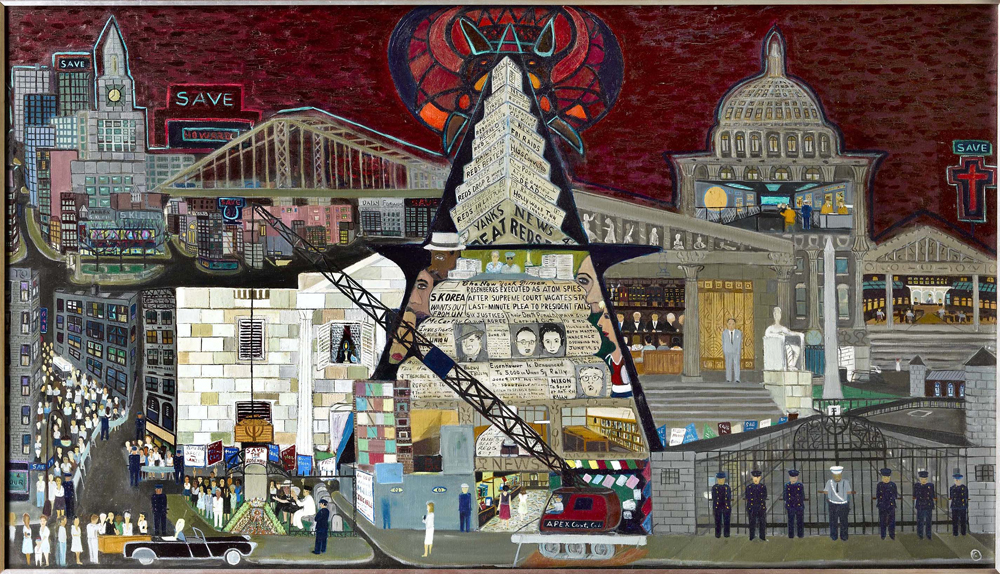

It goes without saying that I stuck it out, and NYC eventually provided all the rewards E.B. White said she might. In my twenties, she helped me figure out how to live in my body: how to feed myself, how to dress, how to embrace my own shadow, how to fuck.  And then, on September 11, 2001, the personal and political entwined in a way that changed my life irrevocably along with the city’s. I fled to Mexico and then upstate, and it was only when my grandfather bought Sadie did I dare return. (I needed an escape pod.) Within a month, my friends began evacuating in droves, freaked by the anthrax threats and the Big Brother-style orange alerts, ready to raise families in the hometowns from which they’d emigrated. Their Holly Golightly years were over.

And then, on September 11, 2001, the personal and political entwined in a way that changed my life irrevocably along with the city’s. I fled to Mexico and then upstate, and it was only when my grandfather bought Sadie did I dare return. (I needed an escape pod.) Within a month, my friends began evacuating in droves, freaked by the anthrax threats and the Big Brother-style orange alerts, ready to raise families in the hometowns from which they’d emigrated. Their Holly Golightly years were over.

But I was ready to transition from Hepburn to Parker, and so I stayed. In the decade that followed I learned how to live in the world: how to write, how to talk, how to be myself on a public platform, and how to get paid for that.

Which brings us to the present, in which another chapter seems to be ending.

As the train malingered this time, I wondered why I never feel like a failure. I am not married. I have no brood. I do not own a home. As of this writing, I do not even own a car. Many of my favorite people and businesses are once again fleeing the city, which is ever less accommodating of artists and thinkers who do not live for a financial bottom line. Bohemian rather than hipster, I still live “on the edge,” which is what my grandfather feared most for me.

So why aren’t I more devastated?

The train slid into Penn Station and I decided to walk down to 14th street rather than take the A train. Just then, the sun came out, and I realized I’d not seen it the entire time I’d been away. The sequence of events reminded me of the bird I’d met right after I’d dropped Sadie off that last time. As I’d walked away from the garage, a pigeon with a bright red head had appeared. I’d never seen one with such markings before, and instantly had flashed on the cardinal that had appeared on my fire escape the day that my grandfather had died, which was also the day that I moved into my current apartment from Poughkeepsie. The cardinal had stayed for the full length of my shivah, and then disappeared on the seventh night.

This pigeon began following me as I walked up the street, and stayed close as I descended down to the subway platform. Passersby stared at us both curiously—me sobbing on a bench, the red-headed pigeon standing guard by my feet. Only when the L arrived did it fly off, and as I watched its departure I felt my grandfather saying goodbye one more time.

This pigeon began following me as I walked up the street, and stayed close as I descended down to the subway platform. Passersby stared at us both curiously—me sobbing on a bench, the red-headed pigeon standing guard by my feet. Only when the L arrived did it fly off, and as I watched its departure I felt my grandfather saying goodbye one more time.

Now back in my finely feathered city, I knew I was in for another phase of evolution. The sun and its emissaries had told me so. I put on my headphones, smiled at the skyscrapers and started shuffling a two-step down the street, just like my grandfather Nathaniel before me. Just like an invisible super-hero, as brave ladies in their middle age are wont to be.

There’s a reason immigrants to the United States of America traditionally came through this island. She is the home for everyone who wishes to birth themselves.

New York, sweet New York, I’m sticking with you.