Earlier this month, Jennifer Jason Leigh turned fifty-four. That’s middle-aged by any standards, not just at-thirty-she’s-over-the-hill Hollywood’s. Yet she’s knee-deep in a renaissance that may transform into a bona-fide career high, if it hasn’t already. On the heels of her much-touted voice work in “Anomalisa,” Charlie Kaufman’s animated feature, she’s received her first-ever Oscar nod for playing fugitive Daisy in Quentin Tarantino’s “The Hateful Eight.” What’s even more noteworthy: It’s her first major role since 2007’s “Margot at the Wedding.”

Earlier this month, Jennifer Jason Leigh turned fifty-four. That’s middle-aged by any standards, not just at-thirty-she’s-over-the-hill Hollywood’s. Yet she’s knee-deep in a renaissance that may transform into a bona-fide career high, if it hasn’t already. On the heels of her much-touted voice work in “Anomalisa,” Charlie Kaufman’s animated feature, she’s received her first-ever Oscar nod for playing fugitive Daisy in Quentin Tarantino’s “The Hateful Eight.” What’s even more noteworthy: It’s her first major role since 2007’s “Margot at the Wedding.”

“I feel like the door was closed, and I had made my peace with it,” the actress told The Guardian last month, crediting Tarantino for her return to the limelight. Though that comment is gracious – and though the writer/director does have a knack for resuscitating actors’ careers (see: John Travolta and Pam Grier) – Leigh’s current success may have more to do with a tenacity that’s enabled her to survive in the film industry since she was a tween. It’s a tenacity that often takes the form of a ragged self-possession, and it’s arguably the only good thing about “Eight,” in which her black-eyed gang leader Daisy reads as a silent film actress amid a babbling brook of men. (She’s the only female lead in the film.) Watchful, wrathful, and impossibly comic, Daisy’s like a grown-up Katzenjammer Kid – if those cartoon characters were out for genuine blood.

Though her grit has lurked even in the biggest naïfs she’s played (witness the wide-eyed prostitute of 1990’s “Miami Blues”), what’s new is JJL is leading with it. In 1991, Entertainment Weekly referred to her as the “Meryl Streep of bimbos.” Though you’d hope a major publication would no longer indulge in such anti-female vitriol, it’s true that Leigh’s resume is studded with “slattern” roles: the street whore of “Last Exit to Brooklyn,” the adaptation of Hubert Selby Jr.’s novel; the phone sex operator of “Short Cuts,” Robert Altman’s adaptation of Raymond Carver’s short stories; the lethally susceptible sister of “In the Cut,” Jane Campion’s adaptation of Susanna Moore’s psychological mystery; the psychotic stalker of “Single White Female,” the adaptation of John Lutz’s eponymous novel. But more than their grasping sexuality, what defines these characters is their pain. Even as a suburban teen trying to shed her virginity in the 1982 landmark comedy “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” Leigh nursed a despair that seemed to belong in a different film entirely. Lest this not seem deliberate, she most effectively – and harrowingly – mines this desperation in projects she’s developed herself, despite the fact that she’s worked with most of North American cinema’s living masters. (The list also includes the Coen Brothers and David Cronenberg.)

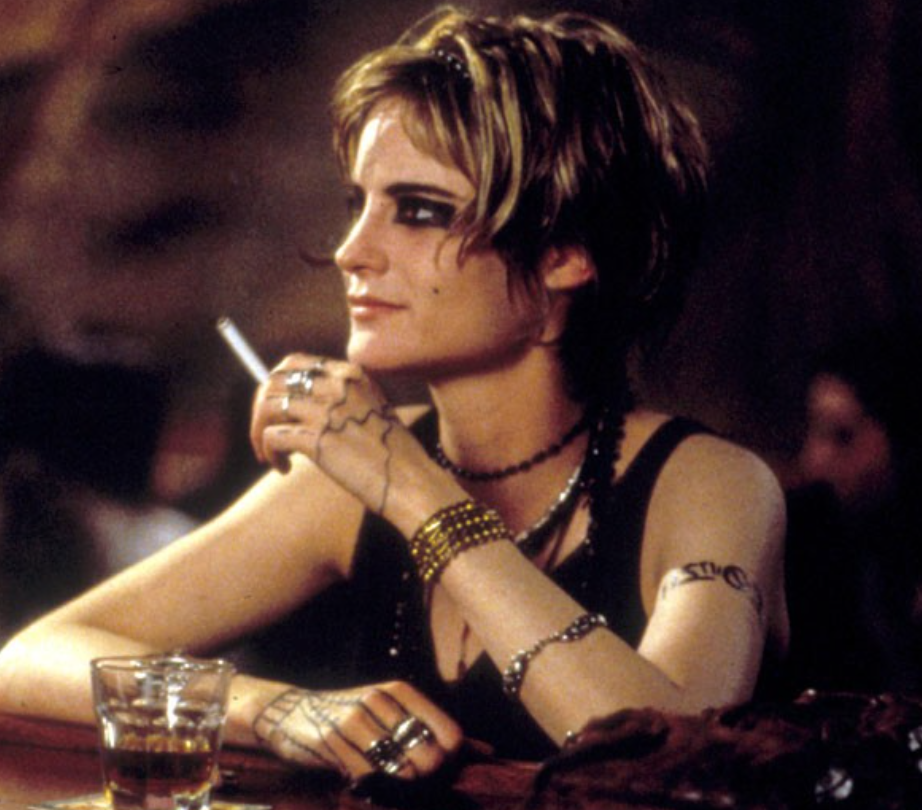

Take “The Anniversary Party,” the ensemble indie she wrote and directed with friend Alan Cumming and peopled with such real-life pals as Jennifer Beals, Kevin Kline, Phoebe Cates, John C. Reilly, and Parker Posey. In it, Leigh plays Sally, a flailing screen actress who doesn’t view herself as a fit wife or potential mother and is described as a “possessive neurotic.” Even as you realize such a title is not false advertising, you can’t look away from her; she is a character who magnetizes us far more than the rest of the film’s glib early-aughts conceits. Or consider the booze-ravaged singer, Sadie, whom Leigh plays in “Georgia” (1995), the indie she produced that was written by her mother, Barbara Turner, and co-starred her camp bestie, Mare Winningham, as the more talented (and titular) sister. When this film came out, I considered it the cinematic equivalent of Sadie’s voice: grating, off-key, unceasing. Yet a few decades later, I’m amazed by what Leigh achieves in it. Her face and scrawny limbs moving in three different directions at once, her kohl-rimmed eyes swelling with a bottomless sorrow, she channels all the qualities of a rock star bent on destruction except the key ingredient of talent. Apart from “Amadeus,” it’s an unparalleled on-screen depiction of the misery of artistic passion ungrounded by ability. It is also so raw that the Academy – under fire once again right now for its inability to recognize brilliance outside its comfort zone – bypassed it entirely, awarding Winningham a nod instead for supporting actress.

“Suffering is a trait you mistake for voice,” Sadie is told at a pivotal moment of the film. For a while, I thought the same of Leigh. Though I admired the honesty of her work, I felt she sometimes held us hostage – that she leaned so readily into her suffering that she blocked out every other element of the human condition. Certainly in her droning Dorothy Parker – all vocal fry and alcoholic nod-outs – little of the author’s enduring appeal can be found. Yet beginning with “Greenberg,” which JJL co-wrote with director (and former husband) Noah Baumbach, she has cultivated a naturalistic no-nonsenseness that boded well. In a small but pivotal role in 2013’s teen drama, “The Spectacular Now,” she exudes defeat and exasperation equally unobtrusively.

She may not take an Oscar this month – up-and-comer Alicia Vikander is the frontrunner in the category of best supporting actress – but I believe Jennifer Jason Leigh has already entered her best phase yet as a film actress. Gone are the baby features that defined her face for decades; gone are the affections that sometimes put even her fiercest defenders on edge. What remains is a radical receptivity that is rarely seen on contemporary screens. For the first time, I can imagine her not just as a Miss Havisham or Lady Macbeth but as an Auntie Mame or even a Mitford Sister. (How are there no films about those British ladies yet?) Unfettered and newly bemused, Leigh has opened the door to a brave new world as a grand dame, something contemporary film has in short supply. Truly, she is a new-millennium model of conscious vulnerability.

This was originally published in Signature.