I withhold not my heart from any joy.— Ecclesiastes 2:10, via Anne of Windy Poplars

I withhold not my heart from any joy.— Ecclesiastes 2:10, via Anne of Windy Poplars

It was a beautiful day. Quiet, full of small satisfactions and a private melancholy that’s become a constant companion this year. I woke early—I suppose the headline would be if I had woken late—and sprang into action. Did laundry, fetched supplies at the greenmarket, made jars of iced tea from pineapple weed and mint and chamomile and ginger and hibiscus. Visited my pal at the hardware store and came home with bags of plywood and paint and gorilla tape. Coaxed one more bunch of peony buds into bloom. Organized a cupboard that had been bothering me for months.

Listened to the Hadestown soundtrack all the while—

You, the one I left behind/

If you ever walk this way/

Come find me/

Lying in the bed I made

and moved gently, gently like the beached mermaid I feel myself to be. Fear myself to be. I’m so cautious these days—afraid of reinjuring the back only recently mended through acupunk and good wishes, afraid of my selfishness and the selfishness of others. Afraid of being this ghost, floating through families and flocks of NYC peacocks, eavesdropping on conversations held and not held.

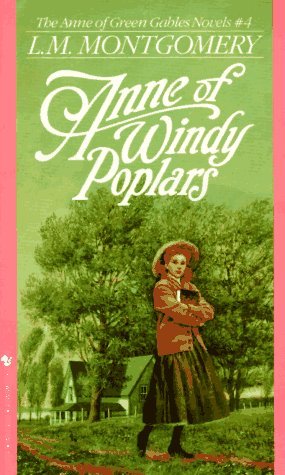

I sat in the park for a long time after finishing my errands, nursing an espresso with ice until it became an Americano, reading Anne of Windy Poplars, the Anne of Green Gables installment in which Anne serves as a school principal in an adjoining town. It’s the oddest book in the series– written last though slipped chronologically in between Anne’s girlhood and marriage, studded with ellipses and redacted passages attributed to Anne’s “scratchy pen.” You sense author L.M. Montgomery sifting through lessons she learned later in life about pettiness and regret and the pointlessness of stony hearts.

It seemed the right selection for the day, and I knew I was right when I finished it in my red dress and red lipstick, on a red blanket beneath the same tree I’d been sitting beneath for 15 years. I felt so moved. Orphan Anne’s faith had not only opened her life but so many others. She had loved many she did not need–it was such an interstitial chapter of her life, so unpopulated by its regular characters. She had loved just the same.

It seemed the right selection for the day, and I knew I was right when I finished it in my red dress and red lipstick, on a red blanket beneath the same tree I’d been sitting beneath for 15 years. I felt so moved. Orphan Anne’s faith had not only opened her life but so many others. She had loved many she did not need–it was such an interstitial chapter of her life, so unpopulated by its regular characters. She had loved just the same.

I closed the book, weeping. One advantage of middle-aged invisibility, I find, is I can weep anywhere I wish. There’s a power in embodying others’ fears. It surrounds you with a forcefield that allows you to feel your feelings in peace. This sounds like self-pity but it’s not. It is more ancient and more soulful. It is accepting rather than running from the human condition. Sorry, but there it is. I’ve got nowhere to go—the universe grounds and grounds and grounds me until I find grace where I am–and this teaches me a lot. Loneliness is the poverty of self, wrote Mae Sarton. Solitude is the richness.

When I climbed the stairs to my shiny apartment—I always clean Friday nights so my weekends feel like a present—I poured myself a glass of water and sat by the kitchen window. Grace climbed next to me companionably, and I scratched her silky chin while we surveyed the darkening city together. After a while I noticed we had two more companions–a pair of doves sitting silently on the fire escape. She was nestled in my flower box, dun feathers ruffled. He was perched above her on the rail, as if on guard. Grace watched them closely, beatifically. When we have mice, I complain about my cat’s pacific nature. I was glad for it now.

We all sat still, looking at each other.

We all sat still, looking at each other.

Then, in one fell swoop, the doves flew off in unison, leaving behind a perfectly plaited nest containing two perfect eggs. Grace looked at me, her green eyes round with questions, and I scratched her some more.

“They’ll be back.”