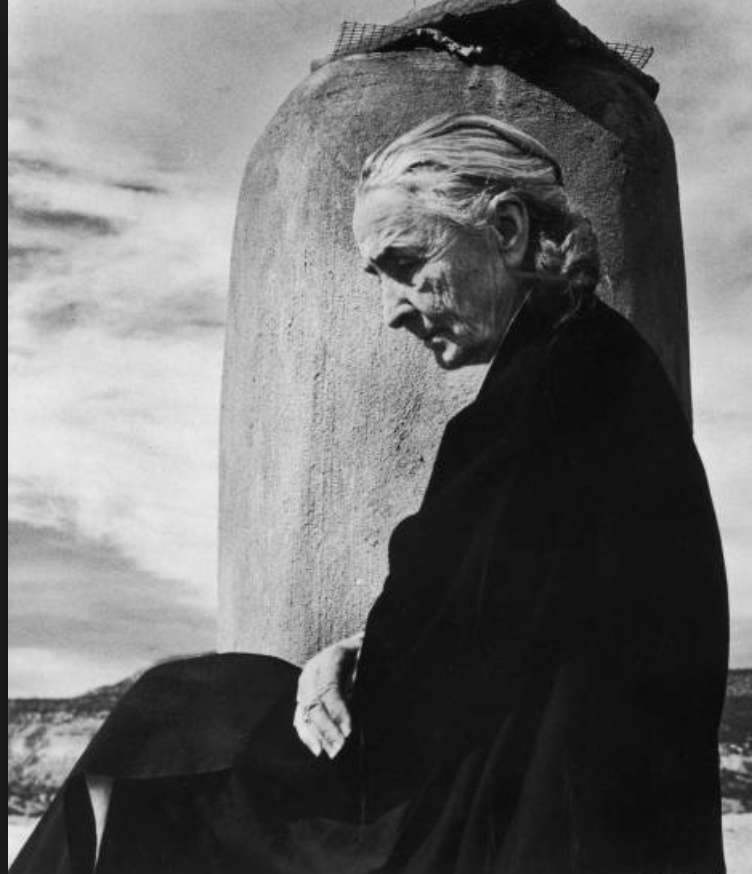

Though the painter Georgia O’Keeffe has been dead for thirty years, she is remembered best as an old woman clad in billowing robes and squinting against a Southwestern sky. This is more unusual than you might think, for once most people die, their oldest self is not what lingers in our memory. Instead, a younger iteration is restored to our consciousness, a la Audrey Hepburn in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” or “Thriller”-era Michael Jackson. Just the fact that it’s not preposterous to compare O’Keeffe to these two pop touchstones says a lot about the iconic status she actively cultivated in her later years. This spring, a Brooklyn Museum of Art exhibit, Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern examines how she subverted conventional tropes of gender, age, and beauty with a dry eye still very much admired today – and how she served as both art and artist long before such a conflation of roles was common.

Though the painter Georgia O’Keeffe has been dead for thirty years, she is remembered best as an old woman clad in billowing robes and squinting against a Southwestern sky. This is more unusual than you might think, for once most people die, their oldest self is not what lingers in our memory. Instead, a younger iteration is restored to our consciousness, a la Audrey Hepburn in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” or “Thriller”-era Michael Jackson. Just the fact that it’s not preposterous to compare O’Keeffe to these two pop touchstones says a lot about the iconic status she actively cultivated in her later years. This spring, a Brooklyn Museum of Art exhibit, Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern examines how she subverted conventional tropes of gender, age, and beauty with a dry eye still very much admired today – and how she served as both art and artist long before such a conflation of roles was common.

Curated by Stanford art historian Wanda M. Corn, the show (which later will travel to the Reynolda House Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts) includes dozens of O’Keeffe paintings and a few of her sculptures, as well as key elements of the artist’s wardrobe, much of which she made herself. (Her boast of being a “wonderful seamstress” in her autobiography is not wrong, if characteristically immodest.) The show also includes nearly a hundred photographs of O’Keeffe by such twentieth-century heavy-hitters as husband Alfred Stieglitz, and Ansel Adams, Cecil Beaton, Andy Warhol, Bruce Weber, and Irving Penn.

I was skeptical when I first heard about this show: “Corn couldn’t score enough of her paintings?” Boy, did I miss the point, for what is highlighted here is a Platonic ideal of O’Keeffe that stubbornly persisted no matter who gazed upon her and what era she inhabited. Her wholly autonomous self-vision was not merely a feminist achievement. It also was a transcendence of the dualities – male versus female, old versus young, subject versus object – that our culture are only beginning to shed decades after her death.

The irony, of course, is that Mz. O’Keeffe was very much a creature of black and white, literally though not figuratively. Selections from her closet are almost all ebony or ivory, and nearly as prim as her visage. There are white silk dresses handmade for her in midcentury New York, black Marimekko gowns, a gaucho hat obtained after her signature move to New Mexico, kimonos inspired by her love of Japanese culture and art, robes and gowns she fashioned herself from bleached-out linens and wools (most of which boast pockets, the ultimate in female liberation wear!), and row after row of black men’s suits. Many of her New York gowns and suits were made by “Knize,” a midtown haberdasher who also made clothes for Marlene Dietrich.

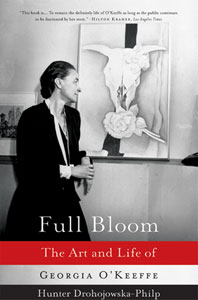

The Dietrich connection does not seem a coincidence, for both women were extraordinary gender innovators (the term “gender-bender” is far too inelegant to apply to either of them)–ones who changed the world rather than letting it change them. In “Full Bloom: The Art and Life of Georgia O’Keeffe,” Hunter Drohojowska-Philp reports that, in their 1905 yearbook, the artist’s high school classmates described her as “A girl who would be different in habit, style, and dress/ A girl who doesn’t give a cent for men – and boys still less.” Like nearly everything else about Georgia, this never changed so much as it evolved.

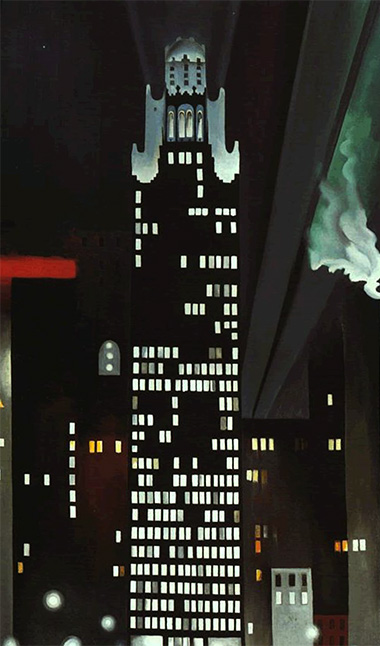

This was especially true of her own art, perhaps because she uniquely gave it room to grow. By clearing out the bulk of societal baggage holding back most women artists – she did not mother (not that this is a bad thing, of course) nor did she conform to most other conventions of female behavior – she distilled not just herself but her world to essences. Even in the mannerly Matisse-style paintings she crafted as a student, you already can see her appreciation of form over function. (“I will only paint what is beautiful!” Drohojowska-Philp reports she declared as a young girl, adding that she rejected social realism as early as her Art Student League days.) In her mid-career cityscapes, she reduced the cacophony of New York skylines to a spectacularly spare geometry, and in her enlarged flowers, tree trunks, skulls, and terra-cotta hills – arguably her signature work – her meticulous sense of detail grounded out the explosion of color reserved for her canvas. Indeed, by keeping her physical being so relentlessly austere, O’Keeffe established she was no one’s fancy – not even her own. She may have painted extravagant odes to female organs, but she herself was clad in beautifully severe uniforms. She was always the person holding the reins.

already can see her appreciation of form over function. (“I will only paint what is beautiful!” Drohojowska-Philp reports she declared as a young girl, adding that she rejected social realism as early as her Art Student League days.) In her mid-career cityscapes, she reduced the cacophony of New York skylines to a spectacularly spare geometry, and in her enlarged flowers, tree trunks, skulls, and terra-cotta hills – arguably her signature work – her meticulous sense of detail grounded out the explosion of color reserved for her canvas. Indeed, by keeping her physical being so relentlessly austere, O’Keeffe established she was no one’s fancy – not even her own. She may have painted extravagant odes to female organs, but she herself was clad in beautifully severe uniforms. She was always the person holding the reins.

The exhibition suggests that O’Keeffe, who lived until age ninety-eight, controlled every aspect of her person – her monkish homes and robes, her nature-based art, even her deadpan presence in other’s photographs, both as an older woman and as a sly-eyed sylph who, let’s face it, nabbed Stieglitz from his wife. Long before most Americans obsessively projected their public image, Georgia O’Keeffe seamed every aspect of herself. The ultimate in modernity, she merged who she wanted to be with how the world saw her. To this day, we continue to ogle.

This originally was published on Signature.