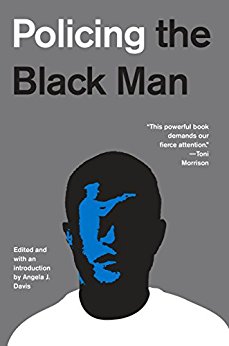

Anyone who has read Freud knows that past is present when it comes to the traumas of our ancestors, especially when we do not consciously heal our family lines. This is also true of nations, which is why so many international wars stem from centuries-old conflicts. It is also why every person living in the United States, regardless of their race, religion, or where their ancestors lived 150 years ago, is impacted by slavery – its unmerited entitlements for white people; its dehumanizing exploitation and abuse of black people. Nowhere is this legacy more evident than in the U.S. criminal justice system’s grave mistreatment of people of color – especially black males. Policing the Black Man, an essay collection edited by activist and academic Angela Davis, lays out how African American men have remained endangered by our law enforcement system since “Juneteenth” – June 19, 1865 – when the slaves in the former Confederacy of the southern United States were officially emancipated.

Anyone who has read Freud knows that past is present when it comes to the traumas of our ancestors, especially when we do not consciously heal our family lines. This is also true of nations, which is why so many international wars stem from centuries-old conflicts. It is also why every person living in the United States, regardless of their race, religion, or where their ancestors lived 150 years ago, is impacted by slavery – its unmerited entitlements for white people; its dehumanizing exploitation and abuse of black people. Nowhere is this legacy more evident than in the U.S. criminal justice system’s grave mistreatment of people of color – especially black males. Policing the Black Man, an essay collection edited by activist and academic Angela Davis, lays out how African American men have remained endangered by our law enforcement system since “Juneteenth” – June 19, 1865 – when the slaves in the former Confederacy of the southern United States were officially emancipated.

A longtime intersectional feminist, Davis is not suggesting that black men are the only people endangered on American soil. In an introduction, she writes:

While acknowledging that other groups have been and continue to be oppressed and discriminated against …. the experience of black men in the criminal justice system is unique …. they are impacted more adversely than any other demographic in the United States at every stage of the process.

Perhaps because each contributor is a specialist in criminal law and justice, this book is about as far as you can get from “fake news.” With meticulous detail and clear, charismatic prose – I’ve never read such fascinating footnotes in my life – each chapter contextualizes a different aspect of how black males are unfairly policed starting on the streets and in schools and through our court system, prisons, and jails. Though some readers may be familiar with the broad strokes, the breadth of perspective here is powerful. Here are just a few of the facts offered that, when assembled, paint a picture that is bone-chilling.

-By the end of 2009, the number of black men on probation, in prison, in jail, or on parole roughly equaled the number enslaved in 1850.

-One in three black men born in 2001 can expect to be incarcerated in their lifetime.

-Of 2,437 elected U.S. prosecutors, 95 percent are white and 79 percent are white men.

In the chapter “A Presumption of Guilt: The Legacy of America’s History of Racial Injustice,” Bryan Stevenson details how the defense of slavery manifested as an ideology of white supremacy that overtly and covertly runs rampant in our culture today, especially because we have yet to confront the history of slavery in a meaningful way. (To date, we have more Confederacy markers than slavery memorials.) He writes:

The narrative of racial difference contaminates the thinking of most Americans. We are burdened by our history of racial injustice in ways that shape the way we think, act, and enforce the law…. As in South Africa, Rwanda, and Germany, America desperately needs to commit itself to a process of truth and reparation.

The book goes on to establish how America didn’t even have a police system until patrol units were created to keep slaves “under control.” It traces how slavery migrated into lynching, which in turn migrated into legal capital punishment and other judicial and law enforcement codes un/consciously predicated on a “white is right” pathology. It parses how the identity of black men as “slaves” evolved into the identity of “criminal” – a template we’ve yet to eradicate. It demonstrates how racial profiling impacts every black male body in this country, and how our laws – even the misinterpretation of key Constitutional amendments – enforce rather that repeal the treatment of black men as “guilty until proven innocent,” especially since the inception of the Drug Wars. We are shown how black men are inequitably pursued, beginning in schools, where a police presence has proven a detriment rather than an aid to the education and guidance of black boys. With a shocking bulk of data, we are shown that prosecutors and grand juries sentence and convict with profound bias and little accountability, and that no governmental agency to date tracks the number of black men assaulted and killed by police officers, though information is amassed about police officers killed by civilians. We are shown how discrimination against minority voters compounds these injustices since it prevents citizens from electing progressive prosecutors and politicians. We are shown how “tough on crime” laws have savaged economically challenged black communities without improving public security. And a final chapter breaks down how American prisons and jails replicate the racial bias of  slavery.

slavery.

To live in this country is to inherit its history of bloodshed as well as its history of positive social change, and educating ourselves about our whole past is more vital than it’s ever been before. Policing the Black Man is not light summer reading. Rather, it is essential reading – a compendium of human rights violations that matter-of-factly questions the reality of American “liberty and justice for all.”

This was originally published at Signature.