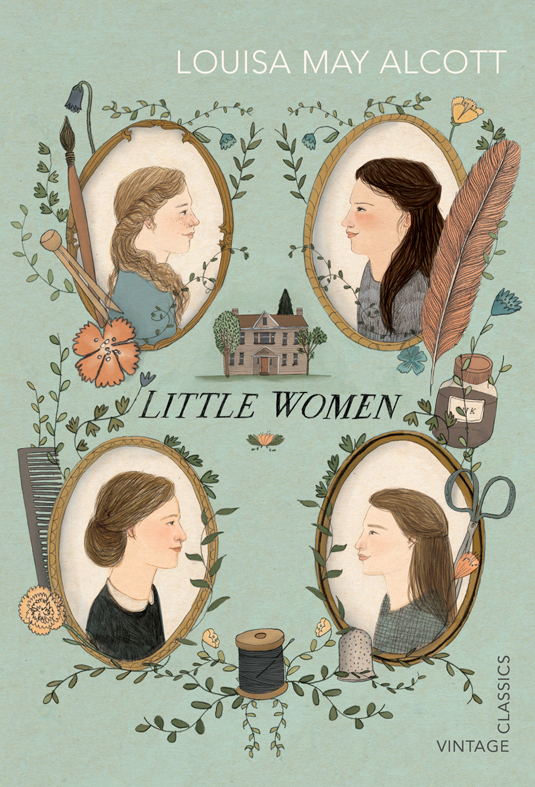

To know Little Women is to love Little Women. From its very first line – “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents” – Louisa May Alcott’s landmark 1868 novel about four cash-poor, rich-in-spirit sisters has captured generation after generation’s love and devotion. The book’ got it all: cozy escapades, romantic triangles, “operatic tragedies,” and delicious descriptions of puddings, velvet gloves, and those infernal pickled limes. There’s pretty, maternal Meg. Artistic, vain Amy. Shy, musical “Poor Beth.” And Jo, the strapping, temperamental tomboy who aspires to be a writer when she grows up.

To know Little Women is to love Little Women. From its very first line – “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents” – Louisa May Alcott’s landmark 1868 novel about four cash-poor, rich-in-spirit sisters has captured generation after generation’s love and devotion. The book’ got it all: cozy escapades, romantic triangles, “operatic tragedies,” and delicious descriptions of puddings, velvet gloves, and those infernal pickled limes. There’s pretty, maternal Meg. Artistic, vain Amy. Shy, musical “Poor Beth.” And Jo, the strapping, temperamental tomboy who aspires to be a writer when she grows up.

Just like everyone is a Charlotte, Samantha, Carrie, or Miranda today, everyone was once a Meg, Amy, Beth, or Jo. I suspect everyone secretly loved the slapdash Jo most; there’s a reason Kate Hepburn played her in the film adaptation.

As an aspiring writer in elementary school, I adored all the sisters and clamored for the “Pilgrims Progress” morals that Alcott, a true daughter of the Transcendentalists, sewed into their scrapes and graces. But the book most came alive when Jo galloped to the forefront. Loyal to a fault, indifferent to the domestic arts, and giving no fig for her appearance, she wrote volumes while decked out in the “scribbling suit” that prompted her family to ask, “Does genius burn, Jo?” As her sisters married or passed away, Jo clung to her dream of becoming a lady author, submitting her work for prizes and publication and even moving to New York City from Massachusetts to make a real go of it.

But as many times as I pored over the book, I usually stopped reading before its very end. It wasn’t because spoiled Amy won Laurie’s love and baubles after Jo spurned his affections. It wasn’t because of Beth’s sorry decline. It was because Jo married Mr. Bhaer, the German scholar who dismissed her writing out of hand. Although the first half of Little Women (the good part, I always thought) comprises a book composed by Jo in the second half, she lays aside her writing to become his wife and the mother of two boys.

This killed me, and I don’t think I’m the only one who felt that way. I was hungry for bildungsromans about budding female writers, and the taming of Jo March dashed my dreams. It seemed so odd that her fate was portrayed as a happy ending. I viewed Beth’s death as less grim.

Though I’ve come to call these literary betrayals as “the Jo March Effect,” this domestication didn’t just happen to her. In 1908’s Anne of Green Gables, Anne Shirley was identified by her pluckiness, her red hair, her imagination, and her dreams of becoming a writer. In later books, she published a story here and there while attending university and working as a schoolteacher to help out her adopted guardian Marilla. But once her longtime beau, Gilbert, made her an “honest woman,” she never wrote again. By the last few installments in L.M. Montgomery’s series, good mommy Anne is eclipsed by her many kids. I hated the series’ final books – chirpy and status quo-enforcing – as much as I loved its first few.

Though I’ve come to call these literary betrayals as “the Jo March Effect,” this domestication didn’t just happen to her. In 1908’s Anne of Green Gables, Anne Shirley was identified by her pluckiness, her red hair, her imagination, and her dreams of becoming a writer. In later books, she published a story here and there while attending university and working as a schoolteacher to help out her adopted guardian Marilla. But once her longtime beau, Gilbert, made her an “honest woman,” she never wrote again. By the last few installments in L.M. Montgomery’s series, good mommy Anne is eclipsed by her many kids. I hated the series’ final books – chirpy and status quo-enforcing – as much as I loved its first few.

In an equally nullifying reversal, Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote eight books about her youth and young adulthood in unsettled 1800s America – the beloved Little House on the Prairie series– without ever acknowledging that the “Laura” character harbored any writing aspirations. Even the time and space-defying Wrinkle in Time series betrays its brainy female protagonist. True, misfit Meg Murry does not aspire to become a writer. But she’s described as a math and physics genius – of possessing a gift she lays aside once she becomes the wife of childhood sweetheart Calvin and the mother of seven. This, despite the fact that Meg’s mother is a nationally ranked scientist and author Madeleine L’Engle herself was a working parent. (A book about adult Meg always has been rumored but to date is unpublished.) True, the titular tomboy and journalist of 1964’s Harriet the Spy never abandons her dreams, but we never meet her as an adult. (It’s doubtful Louise Fitzhugh ever would have made her a carpool mom, but since the queer author died suddenly we’ll never know.) Of classic young adult fictional heroines, only Betsy Ray of Maud Lovelace’s Betsy-Tacy series (written in the 1940s and ‘50s) stands out as a girl who realizes her childhood dreams of becoming an author as well as a wife. But though equally engrossing and endearing, these books are not as widely recognized these days–a great loss to the YA canon, given the shining and rare example they offer.

In sooth, all these YA classics are great time capsules and even greater allies for female readers of any age (all readers, really). But it’s interesting, even disturbing that such ambitious lady authors couldn’t, with the exception of Lovelace, grant their literary stand-ins the sort of success they themselves achieved. Doing so would have meant so much for the young female aspiring writers. Alcott, pretty much a real-life Jo, supported her parents on her literary earnings while never marrying herself; she famously declared “I’d rather be a free spinster and row my own boat.” Wife and mother Montgomery published books her entire adult life and considered it a vocation, not a hobby: “I am frankly in literature to make a living out of it,” she wrote to a friend. So why couldn’t these women writers leave some fictional breadcrumbs for ambitious young girls?  Were they afraid they’d lose audiences if convention was flouted? Did they fear cultural unrest? Or did they prefer status as what Adrienne Rich describes in Of Woman Born as “exceptional women” – that is, as a cut above the rest?

Were they afraid they’d lose audiences if convention was flouted? Did they fear cultural unrest? Or did they prefer status as what Adrienne Rich describes in Of Woman Born as “exceptional women” – that is, as a cut above the rest?

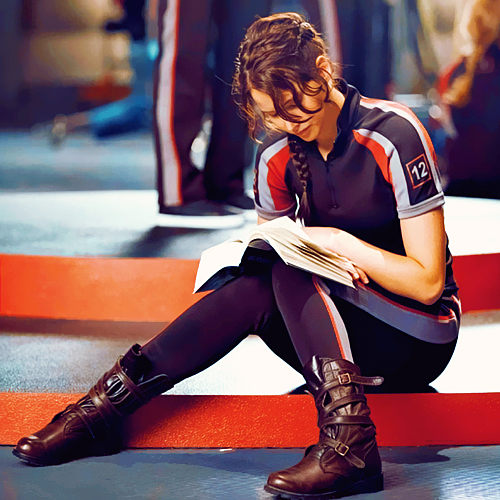

Many aspects of modern life are banal at best, deplorable at worst. Ethics, etiquette, the environment: Standards have plummeted since Alcott and Montgomery were alive. But it’s hard to imagine a contemporary young adult series that would sell its bad-ass, creatively enterprising female protagonists down the “good girl” river the way these authors did without batting an eyelash. If Katniss Everdeen excelled at writing rather than archery, you can bet your bottom dollar that she’d “write the book that made the great war,” as Lincoln once said of Harriet Beecher Stowe. Progress may not always be linear; just look at how Donald Trump replaced Barack Obama in the White House. In the case of our YA literary heroines, though, it’s as straight as an arrow.

A version of this ran in Signature last year.