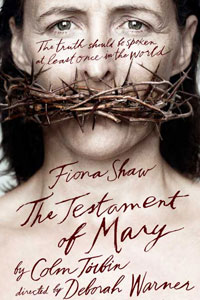

Now that The Testament of Mary, actress Fiona Shaw’s latest theatrical collaboration with director Deborah Warner, has closed after only a few weeks, it’s probably poor form to stomp upon its grave. But stomp I shall. This Broadway adaptation of Colm Tóibín’s novel about Jesus’ mom after his crucifixion proved so bottomlessly negative that, if it’s slightly blasphemous to kick a play when it’s already down, then at least blasphemy about purported blasphemy may amount to a double-negative positive. Pretty to think so, anyway.

Now that The Testament of Mary, actress Fiona Shaw’s latest theatrical collaboration with director Deborah Warner, has closed after only a few weeks, it’s probably poor form to stomp upon its grave. But stomp I shall. This Broadway adaptation of Colm Tóibín’s novel about Jesus’ mom after his crucifixion proved so bottomlessly negative that, if it’s slightly blasphemous to kick a play when it’s already down, then at least blasphemy about purported blasphemy may amount to a double-negative positive. Pretty to think so, anyway.

There’s not much more pretty to be found in this production, which features a Mary who’s hardly a picture of beatific peace and purity. Pacing the room to which she’s been relegated since her son’s death, she smokes, drinks, bellows, gnashes her teeth, matter-of-factly strips, and calls bullshit left and right. This is a Mary who’s not buying the claim that she gave birth to the son of God. If she were the type to pun—and she’s too pissed off for such folly—she’d likely call the fallout from his death a crucifiction.

Before the play officially begins, Shaw sits, uh, mum in a centerstage elevated glass box, draped in soft flowing fabrics and decorously posed, the very picture of the Mother Mary statues flanking every corner of my Italian-American neighborhood. Audience members from the orchestra seats file onstage to ogle her and the haphazard set: furniture upturned, books and barbed wire strewn wily-nily on the floor, and old newspapers stacked in piles upon piles—the international sign for “crazy person.”

But once the lights darken and everyone settles back into their seats, the box lowers and Shaw steps from her throne, instantly breaking the reverie. “They want to know what happened,” she says, drawing in on a cig and exhaling slowly. “Memory has filled my body.” It’s clear it’s an unwelcome invasion. Pacing the stage fitfully, she changes her clothes frequently, as if she were trapped in that state of misery and rage and discomfort when nothing feels right, not even your own skin stretched across your skeleton.

Slowly, her version of her son’s transmutation emerges. It is not unlike the story of many women who feel abandoned and betrayed by their offspring. Her sweet son grew too big for his britches. He got mixed up with the wrong crowd, dangerous people who encouraged his folly and led him to trouble. He disrespected her in front of others. He flew the coop and never came back. In her dotage she has been abandoned with no creature comfort, not even the sanctimony of the blameless, for she is horrified by how she abandoned her son as he died upon the cross.

She speaks in hoarse, ragged tones, and when she really gets up in arms, screams a smoker’s impotent scream. It is totally empty of force. “He used such strange, proud words,” she rages. “He said, ‘Woman, what am I to do with you?’ But I am not one of his followers.” When she relays how he changed water to wine, she scours the event for evidence of his manipulation. Where did those kegs of water come from? she wonders. It all seemed a little, well, convenient, didn’t it? She’s your standard impossible-to-please mother here, blaming everyone, including herself, and nurturing none. A Thoroughly Modern Mary, disenfranchised and alone. You can practically hear Shaw, Warner, and Tóibín slapping themselves on the backs for their radical subversion of the Good Mommy paradigm that forms the backbone of Christian mythology.

In the final moments of this trying exercise—for Mary’s circling of the drain is as dull as it dour—she relates how his spirit visits her after his death: “He told me he was suffering so that mankind could be saved.

I say: it was not worth it.”

And then the stage goes dark.

To be fair to the production, the acuity of my disappointment stems from my dashed hope that I would find the Mary I’m endlessly, fruitlessly seeking in religious and artistic forums.

Having been raised by parents who’d largely rejected their Episcopalian and Jewish upbringings before my birth, I was raised to believe that anyone who subscribed to that “Jesus and Mary stuff” was like a grownup who still believed in Santa Claus: a little dim, a little desperate, a lot misguided.

But somewhere along the line I began to sense, even to bask in a divine intelligence all around me. I tapped into it whenever I stepped outside my parents’ house into the big weather and small kindnesses the world produced so matter-of-factly. It gave me strength to move forward when my will and willingness otherwise seemed inexplicable. It offered me simple, sweet miracles during my Ruby Intuition sessions with even the most blocked of clients.

For all practical purposes, I began to view this divine intelligence as the mother whom I’d never experienced but always craved, the one most of us seek our whole lives in work, love, our reflections in the mirror. A capable nurturer who understood and loved us even more than we could understand and love ourselves. A divine mother, in other words: compassionate, empathic, wise, receptive, gracious, regenerative. Whole unto herself.

At which point I began to reconsider the Mary who’d allegedly given birth to Jesus. Forgive me, but I’d always viewed Mother Mary as one of the original dumb broads. Famous for allegedly getting knocked up without even the benefit of sex? Not my kind of heroine, let alone heroin. But now I began to rethink that myth. Here was someone so pregnant with divine intelligence that it literally filled her. More to the point, her faith in herself and in her connection to something bigger hatched something from nothing. Which is what so many of us, those of us who haven’t given up on ourselves and others, are all trying to do. When we hold out for authentic comfort, connection and communication rather than that which is both compromised and compromising. When we remain empathic and receptive even in the face of hard times and hard people. When we allow our trauma to surgically open our hearts rather than sear them shut.

Dumb broad, my ass. To remain that open you must be not only tough but smart. Divinely intelligent, even.

So I began to recognize Mary, all Marys in history, as exactly what was missing from our common culture. Yet no matter much I tried, no matter how many sermons I sat through and various temples and churches and even ashrams I visited (and there were a lot), I could not find her beautiful receptivity, not to mention her son’s beautiful messages of healing and compassion, in any organized religion. I began to feel like the medieval French nuns I studied in college who were forced to live outside the Church because of their craving for a more direct relationship with God. Not having been raised within any religion, I found it impossible to take any of it seriously as an adult though I envied and respected those who did; the more I became “a believer,” the more I longed to share my faith with others. But it all seemed so hierarchical, so constrictive, so arbitrary. In my experience faith proved anything but blind and yet, admittedly from my eternal outsider’s perspective, blind faith seemed to be exactly what was required within the walls of any place of worship. When I burst into helpless giggles during a Unitarian Easter service (in my defense the children of the congregation were blithely blowing bubbles while the choir warbled “That’s What Friends Are For”), I realized an outsider I would remain, left alone to cobble together my own spiritual traditions with statues of Mary; sage and incense; pilgrimages to the desert and sea; postcard images of such soul mommies as Madeline L’Engle and Mae Sarton; morning meditation; evening prayer; grace before meals; matter-of-fact alms; rigorous (if not always effective) self-reckoning; daily communion with my permakitten Gracie Rosman; spirituals by the likes of Aretha Franklin and Joni Mitchell; Sunday morning church at the movies; ad-hoc witchy circles with like-minded friends; and, as my bibles, the myriad dog-eared books of poetry, fiction, and essays that awaken my heart.

But maybe outside is a better place to begin. If this yawning rejection of the Church’s polarizing dichotomy between spirit and body, love and lust, Madonna and whore, even wo/man and God, is any indication, it may be better to have grown up without such polarizing myths. At least I’m not tempted to toss out the baby along with the holy bathwater. After all, I’ve not been baptized in it.

For if the wearying one-trick pony that is Testament of Mary teaches us anything, it is that, for many who grew up within a restrictive religious structure (and I’m not suggesting all religious contexts are restrictive), the best that can be mustered is a fuck-you. A denial of bullshit that, while necessary to raze all corrupt structures, may complicate or even preclude a more positive relationship with the divine feminine. With—as my grandmother always spelled it—G-d.

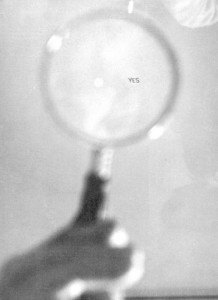

Perhaps the most modern Mary message is that of Yoko Ono, whose brilliant grace is even now eclipsed by her union with John Lennon. The story goes that he fell in love with her when, after traipsing through a series of hoops and ladders in an art installation she’d created, he was handed a magnifying glass through which he could view a tiny message printed upon the ceiling.

It read: “Yes.”