Once when I was 9, a mother and her two kids disappeared from our neighborhood. It wasn’t a kidnapping. It was just that for years they lived down the street from our house, then one day they were gone.

Once when I was 9, a mother and her two kids disappeared from our neighborhood. It wasn’t a kidnapping. It was just that for years they lived down the street from our house, then one day they were gone.

The husband was still there, but when my mom took my sister and I around to visit his wife and kids, he said they were out. His normally polished appearance was unruly—clothes rumpled, face unshaven—but he offered no further explanations and shut the door before my mother could ask any more questions. When we went back the next day, he didn’t answer the door, though his orange Volvo was parked in the driveway. Nor did he answer it the day after that.

For a full week my mom kept finding reasons to drop by. A cutting from her favorite fern, an invitation to take all the kids to the park, cookies she’d just baked, a mug that seemed up the wife’s alley. My mother liked to collect things for people, like a mother bird dragging treasures back to her chicks safe in their nest.

But no matter what time of day we stopped over, no one ever answered the door. The orange Volvo was always there, each day covered with more leaves, but the mother’s car never reappeared.

The real reason my mother kept looking for this woman is she was one of the few people in our neighborhood whom my mother liked. Having spent her young adulthood in downtown Boston, she’d never cottoned to the suburban town to which my parents moved after I was born. She never said it directly—my mother said almost nothing directly—but even as a kid I could tell she found the other mothers in our neighborhood grating or phony or both. She relaxed around this woman–told jokes, pulled faces, lingered over coffee.

I liked this woman too. Let’s call her Audre, because it’s close to her real name and she possessed the practical, large-hearted lyricism of Audre Lorde, whom she liked a lot.

Back home we spent a lot of time wondering where Audre might have gone. Was she sick, I wondered. Does she not like me anymore, wondered my mother. It was my father, surprisingly, who came up with the right answer.

Maybe she left her husband, he said.

Audre had moved to Boston from Brooklyn, which seemed as exotic to my mother and me as Jamaica, which is where Audre’s mother had lived before she moved to Brooklyn to save enough money for a brownstone. After nursing school Audre had met med student James in the hospital where they both worked, and when he took a residency in New England, she moved up North and married him.

I learned all this from listening at doors, which is how I learned most things about grownups who didn’t let me participate in their conversations. Audre wasn’t mean to children but she wasn’t the type to pretend they were adults, so when she wanted to have an adult conversation she expected you to make yourself scarce. Miriam, my mother’s best friend who was my godmother because I told her she was, would let me listen all day while she smoked cigarettes and told thrillingly long stories about her bad boss and bad boyfriends.

But I liked Audre too. She wore big earrings and wrapped ochre and turquoise scarfs around her hair, and she had a soft voice and a big laugh and an easy way of seeing you without making you squirm and correcting you without making you cry. She was not nice, but she was kind.

When my little sister would whine—and my sister had an especially grating whine, like an English wartime siren—Audre didn’t try to reason with her like the mothers in West Newton Hill, the well-off liberal section of our town. Nor did she swat or snap at my sister, like the Irish and Italian mothers of the Lake, the working-class neighborhood on our side of the tracks.

Instead, Audre would regard my sister for a long minute before saying: “Can you say that again in your deep voice, Jennifer?” And we’d all burst out laughing, even my sister, who never had much of a sense of humor. Because really it is impossible to whine in a deep voice, especially when you are a small child and not a white male politician.

My mother had met Audre at a play group, which is what it was called in 70s Greater Boston when the mothers wanted to put all their kids in one room while they drank wine in another. The two women hit it off immediately—two beautifully adorned fish out of city water—and soon enough our afternoons were spent in Audre’s yard and house. Rarely did she and her two children visit ours.

That wasn’t just because my professor father was often home. Audre’s husband was often home as well though, squirreled away in the attached office where he saw patients for his private psychiatry practice, he didn’t make his presence felt as my pipsqueak father did.

Mostly I think we spent our time at Audre’s house because it was so nice. Not plastic-covered and hyper-sanitized, like the houses in the Lake. Not constipated by strict politics and carob cookies like the houses on the Hill. And not noisy and dark and messy, like our house.

Audre’s house smelled of lemons and fresh coffee and cardamom, and was wonderfully ordered with braided rugs and blue stained glass and mustard velvet couches and burnished wood tables. Original art, record albums, masks, books, plates and turn-of-the-century tools hung on the walls. When I visited the Barnes Foundation while attending college in Philadelphia, I remembered Audre’s house and smiled with a quiet awe.

Audre was one of the few people who could produce that smile in me.

Her son Isaac was a few months older than me but three inches shorter, and her daughter Jasmine and my sister were both six. I didn’t like that many kids, but the four of us were happy as clams to disappear into various corners of the house while our mothers talked about whatever it was they talked about when I was too amused to spy on them. Even then I knew it wasn’t their marriages. My mother wasn’t the type to complain about her husband because she wasn’t the type to leave him no matter how much of a pill he was. She referred to my father mostly as Him and He—a constant, not a variable. And definitely a pill.

I think my mother thought Audre was like her in this regard because they had so much else in common. They were both big-boned and nearly six feet; gorgeous with high cheekbones and full curving mouths. Creative and watchful Cancers, which is to say: change-averse, if not exactly change-phobic. Certainly not so big in their britches as to get anything like a divorce.

That’s what my mother had thought, anyway.

That’s what my mother had thought, anyway.

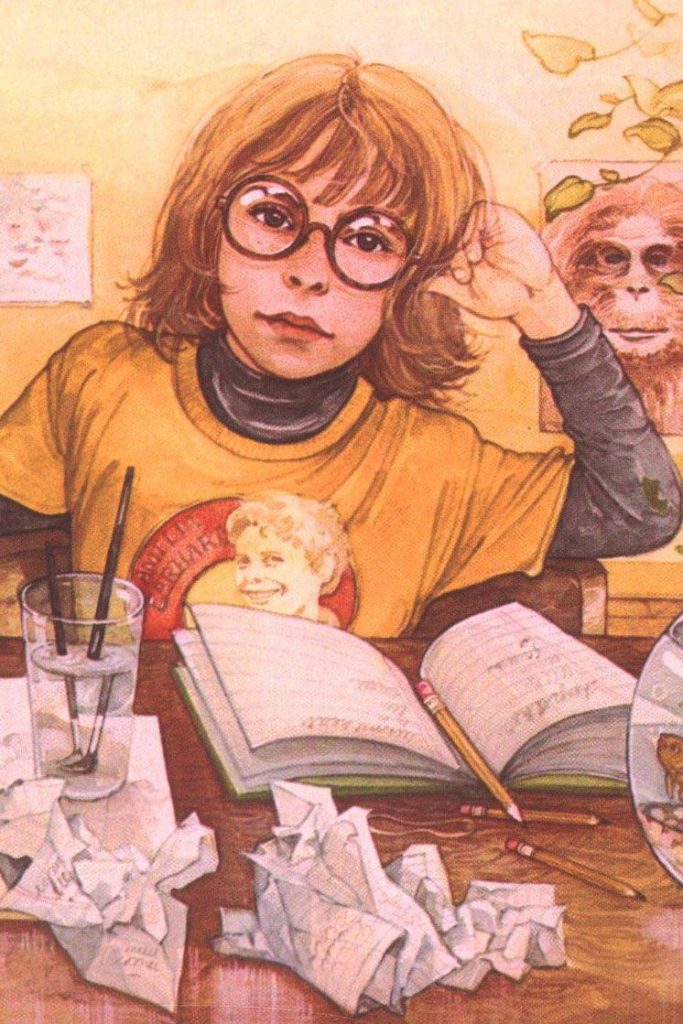

Their absence that Fall didn’t affect my sister and me too much. Since Jasmine and Isaac went to a different elementary school—the mile between our houses put us in different districts—we wouldn’t have seen them as often anyway. But as the weather grew cooler, my mother began to disappear right in front of us. She’d doodle on the newspaper instead of reading it, stare out of the window for hours at a time. Sometimes I’d come home from school and find her in the same place I’d left her, breakfast dishes still piled on the kitchen table. We’d always taken it for granted that my father had to nag my mother to get any big chores done, but now the to-do lists he printed for her in his cramped block letters included basics like TAKE KIDS TO SCHOOL GET GROCERIES GO FOR A WALK.

On Saturdays she still revved into gear. It was no coincidence that was the day she had full access to the car. During the week my father claimed it for work and didn’t think she needed a second one to do chores. I don’t teach every day, he’d point out. You can work around my schedule since that’s the money maker.

Even at that age I’d sometimes advocate on her behalf–the Lorenzos are selling their Datsun for cheap! We’re the only family with just one car!–but she’d look deliberately blank as I did so. Even now I’m not sure if it’s because she didn’t like being aligned with me or because she never directly opposed my father. Keep him in mind she called him Daddy half the time. Keep in mind she married him a few months after own daddy died.

I didn’t even call my father Daddy. I called him Dadzom, his Imperial Fathership. Sometimes just Bernie—Beanie, if I was being fresh. Flipping through his highbook yearbook I’d noticed this misprint beneath his picture. I called my mother Sari most of the time—Mary Susan if I wanted to get under her skin. Years ago she’d changed her name to Sari but her family had never gotten on board. Sometimes I’d call her Ma like all the other kids in the Lake. This pissed her off the worst and she didn’t mind letting me know. I was the the pill she could actually pop.

So only on Saturdays was she was free with wheels, and she’d whiz into Allston to fetch Miriam, waiting in front of her Comm Ave building with high boots and glossy wig and Virginia Slims. The two of them would cruise thrift shops and yard sales, and eventually make their way back to the burbs, as Miriam would refer to our town while exhaling her smoke like a period on a death sentence. I worshipped Miriam so much that it’s amazing I never picked up the cigarette habit.

I worshipped Miriam so much that it’s amazing I never picked up the cigarette habit.

But though Friday nights were date nights for Mirm, as I called her, my parents rarely went out together. We took it for granted that he’d disappear up to his study while the rest of us watched Wonder Woman and ate popcorn.

Then one Friday I came home from school and my mother said not to get comfortable, that she was taking Jennie and me into Cambridge to see Audre and the kids. There was so much to unpack in that declaration that for once I didn’t say a thing, just went out to the Toyota and buckled into the front seat before my sister could scream shotgun.

Read on for Part II (final installment).