Last night was summer solstice and I stood in the darkness by the river, weeping without entirely knowing why. It had been a beautiful day but lonely. After sessions I had mourned my solitude even as I’d appreciated its authenticity.

Last night was summer solstice and I stood in the darkness by the river, weeping without entirely knowing why. It had been a beautiful day but lonely. After sessions I had mourned my solitude even as I’d appreciated its authenticity.

Its charge.

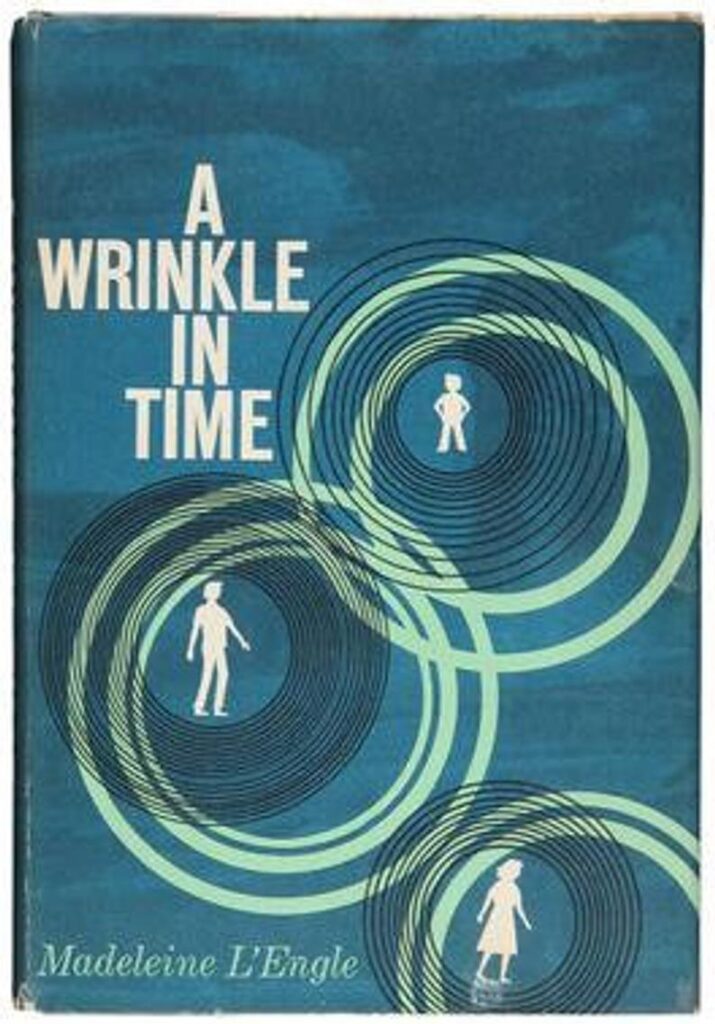

I woke thinking of my grandmother’s funeral and knew she had come through again. She doesn’t return often–only when I really need her. She rarely shows up in a big glorious visitation because that’s not how my intuition works and that’s not how she works. She arrives in an essay, a wrinkle in time, a shining, shared solitude.

She died a few days before my 18th birthday; the funeral happened a few days after it. I was so conscious that no one could ever again legally lay claim upon either of our bodies.

We were free, and it was terrible.

I had loved my grandmother and not felt sure of her. That’s the best way to phrase it. It’s not that she didn’t talk. She spoke when she had something to say. She just wasn’t the type to hold forth. More, she was was the type who listened and to whom others paid court.

By default and by virtue of her quiet self-possession, she was the matriarch of our large, wild family. There was no patriarch. My grandfather had died when he was not much older than I am now, and I’m not sure he ever reigned easily. I never met him –he died months before my parents married–but heard tell of fights, fugues. Futwahs.

My grandmother reigned easily. Everyone confided in her—speedily, anxiously—and she listened with the lids of her large blue eyes lowered at half-mast. You could never tell if she was rapt or bored. That question lived at the center of every exchange she ever had, I think.

I visited as often as possible in her last few months. I clamored for her company because if anyone was grownup in our clan–anyone in my life–it was her, and in my last year of high school I needed a grownup. The future did not beckon. It loomed, a vast cloud of a horizon.

I’d skip last period and hitchhike out to her bedside in the downstairs of my aunt’s dark, dank house. My grandmother wasn’t sitting up anymore. She was lying prone and alone, staring at the ceiling as my aunt busied herself elsewhere. As all my grandmother’s children did.

Gone were her dentures, her long white tresses. Even the spectacles on her near-sighted eyes. Sometimes her tongue would snake out around her lips and I would glimpse that deep terrifying canyon of a mouth no longer in use. Over and over, she would taste her lips, as if seeking something eluding her grasp. Effort lived in that action. Will.

It was the first time I’d felt her disquiet.

I would talk to her, prattle, really–desperate to connect now, desperate for a sign that someone of substance cared what I said and did–and she would train her gaze on me, even more wordless now. I told her of my studies, not of my boyfriends. I knew better than to bother her with them.

Once I really blew it. I said, “You lived a good life, right?”

She made a noise and I looked over at her. It was, I realized, a snort.

That snort answered more questions than I’d wanted to ask. Spoke of the children I’d always suspected she’d not wanted. The husband. The din.

When my grandmother was a teenager, her factory family had moved to Australia to find work. America has been hijacked by the Depression, and they were desperate. A few years later they came back, but she stayed. She was 18 and on her own. I don’t remember her telling me about this, but I remember knowing it. Knowing how she’d thrived.

Then my great-grandmother wrote that she had to come back. In her prim penmanship declared it wasn’t proper for a young woman to live alone, with her family clear on the other side of the world.

So my grandmother came back.

When I was a kid, my mother once told me, my mother would lock herself in the bathroom with a book. We’d be banging on the door, but she’d wouldn’t come out all afternoon. Not until it was time to make supper. She always came out to feed us.

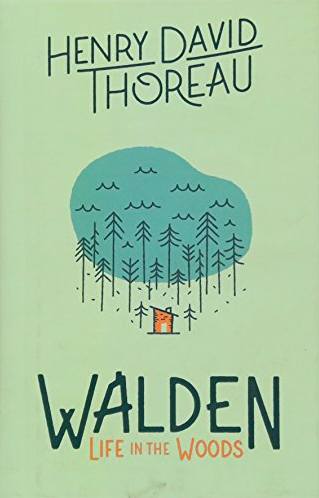

I was reading Lear that semester in school but even then knew it was too on the nose. So I read to my grandmother from a book of Transcendental poetry. She liked the Transcendentalists.

If she liked me at all—and like is so very different from love—it was because I was the only person in her life who also valued the transcendentalists. Who would even know them. By the end of my grandmother’s life every surface of her house was covered with volumes few would have imagined an uneducated 20th century widow from the Massachusetts mills might read. Ones on communism, Buddhism, labor law, social psychology, physics. And, yes, transcendentalism.

A pagan scientific sort of god—who Einstein might have believed in, who danced with the seasons and at the intersection of time and gravity—flourished at the center of my grandmother’s consciousness. The rest of us blathered on and she let us hang ourselves with our tongues while she held hers. But her concentration was complete.

It was years later that I realized I knew things the way she did. As in: just knew. Though while she was alive I never knew how she felt about me.

I knew she didn’t care if you were queer or black or Jewish. Her husband had, but she was glad to no longer live under that shadow. Her ragtag family was many things, and she held all of it in her even, blue gaze.

She didn’t care much for organized religion, though. She didn’t say it, but wouldn’t go with the others to church. The family might have been Episcopalian but my grandmother, quietly, was not.

Which is why, when she finally left the body, we didn’t send her home with a priest. Someone—eh, it was probably my bright idea—decided I would deliver the eulogy instead. In a fog I sat up the whole night before her funeral and wrote. Asked her to come through and immediately learned it was easier to hear her now that she was not embodied.

I wrote of her bright denim eyes, and the love that had lived in them. That keen love.

I was pretty sure I was right about that, but as I presided at her coffin— clear-eyed and spine straight—I was more concerned with caring for her kin. Here was a collection of humans atoms that had been broken far longer than they’d been whole. I needed them to feel seen and heard one more time before her body was put in the ground and I fled the region for good.

I needed them to feel loved.

It was the first time I’d read my work in public, and I was clocking that fact too. Clocking how my words stirred people, whose eyes welled up. My father was weeping. I had never once seen him weep.

I was a monster, I thought. A Svengali.

I was 18.

Afterward, my Uncle Alfred, the youngest of my grandmother’s children, the most tender-hearted, the most fragile, the most like her in manner if not mind, came to me voluntarily for the first and only time I can remember. He asked for a copy of the eulogy, and again I felt like a monster.

Because I was proud.

My sister sidled up to me—my only sibling and someone with whom I have never connected in all the years we’ve both been on this earth. That we share genes and a childhood home only sharpens my solitude.

“Ya, that was pretty good,” she said, snapping her gum like our father. “At first you were just acting but it seemed like you meant it at the end.”

I was relieved. If my sister approved, perhaps I had served well despite myself. She was never blinded by love.

.

There’s one more thing to say about that day, and I guess it’s why I’m writing. After the service, we congregrated at my grandmother’s house because that’s where we’d always congregated. Everything was as it had been. The heavy scent of cigarettes rising from her scratchy green couch, peeling paisley wallpaper, many piles of books. We sat at the lace-covered dining room table, on her piano bench, on the braided rug and pored through boxes and boxes of old photographs one of my cousins found upstairs.

When my grandmother was alive, we’d never have gone through her belongings. Even now, looking at her pictures felt disrespectful.

She was never a beautiful woman, I saw. Aging had actually helped her looks. False teeth had fixed her gross overbite. Time had carved out cheekbones that better balanced her pudgy features. Had willowed out a waist.

But what shimmered most in these images was something I’d not recognized before. Amusement.

And, yes, love.

Love for every single person taking a photo of her. Love for everyone assembled around her. Maybe not like. But the amusement–the patience!–borne of love.

It was cold that day—cold even for a January in New England before climate change really set in. The sun had not been shone in days but I had not minded. The chilly drear felt right.

But as my cousins and I knelt in the detritus of my grandmother’s life, the sun suddenly emerged. In a reverie, I stepped onto the porch and felt the temperature rise—ten degrees? Twenty? Thirty? I looked up in wonder at the light breaking through the clouds. It was–

For a woman who’d been born and raised in northern Massachusetts, my grandmother had never tolerated the cold. Kept the thermometer at 80 even when she could barely make ends meet.

We pulled off our coats and wandered onto the tiny road where her house was perched. No one would ever call this road a cul de sac. It was a dead end.

But my grandmother was shining.

It was terrible and true, like all the love we share in this life that never finds its footing. Like this freedom I’m experiencing now.

Like the sun itself.