So as I’ve been lying about in a radioactive glow from an especially nasty flu, I’ve been inspired me to go back and look at Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974) and Paul Mazursky’s An Unmarried Woman (1978). It’d just occurred to me that Leigh’s feminist-second-wave Vera Drake has an interesting precedent in these two films. Plus An Unmarried Woman keeps showing up on the WE Channel, which is my most shameful secret viewing vice besides Oxygen and, well, Lifetime. I am a woman who loves Women’s Entertainment television programming, apparently. Hear me roar.

Both of these films were made by very accomplished male directors smack dab in the heart of women’s liberation. Remember the ERA? At that, remember when people even wielded the term women’s liberation with nary a smirk? Or was that smirk ever successfully suppressed? (I was but a lass, it must be said, and my mom and her girlfriends were too busy drinking coffee and making fun of their husbands to be duly invested in a revolution.)

At any rate, An Unmarried Woman makes me reasonably happy; Alice does so only remotely. I’d remembered it as hard to watch, and not in that rewarding drink-your-French-cinema

-it’s-good-for-you way. Watching it again, I regret to report that it’s still a bit of a drag. I dig that it’s the story of a Southwestern working-class woman who harbors artistic rather than middle-class aspirations — an awfully rare distinction these days — but Scorsese is off his turf here both topically and geographically. Partly this has the dutiful feel of a studio assignment, which it really was (his first). Partly he doesn’t seem to like women: Beware the wrath of the ugly short man.

Alice (Ellen Burstyn) is a mom who’s been newly widowed by a man whom she feared more than loved. She finds a new job in a new town as a singer, but loses it when a new lover turns out to be a married psycho (Harvey Keitel, using his beady eyes to good effect here). Then she works as a waitress in a podunk Arizona town, comes crankily to the revelation that she’s never learned how to live self-reliantly as a woman, and so naturally enters a relationship with a rancher who’s not nice to her kid. To be fair, the kid is that staple of the divorced-parent movie: a smart-mouthed, precocious toad. Worse, he wears aviator glasses and hangs with a baby dyke Jodie Foster, revving up for a stint as a Taxi Driver’s child prostitute. The film’s not very nice to look at, except for the opening segment, a Wizard of Oz homage flooded with blood-red. It’s strange to watch Scorsese fool idly with techniques such as fast zooms that he’ll use to such better effect later. Mostly the film is filtered through the grainy, sun-dappled lens and cinema verite shtick that was the downside of 70s cinema.

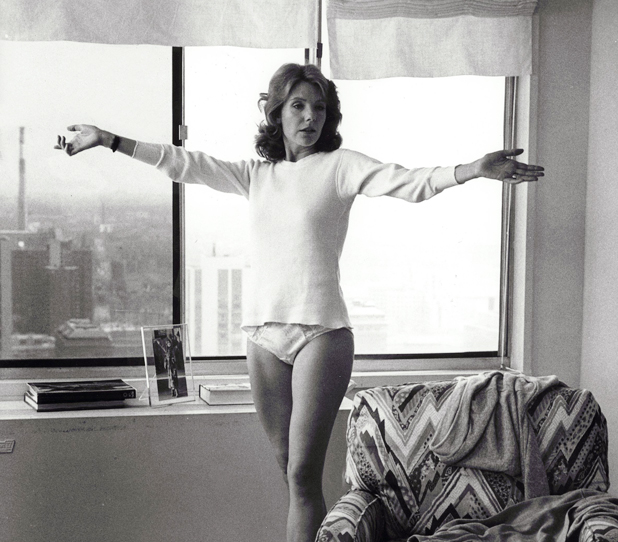

An Unmarried Woman amuses me more, basically. It’s set on the Upper East Side and in a very nascent Soho. It’s always fun to look at New York in the other eras, and Mazursky excels at pleasantly gossipy, two-hour social tableaus. God love Jill Clayburgh’s cowl-neck sweaters and capes; the small glasses of white wine in the “single bars”; the enormous artists’ lofts littered with the abstract paintings; the jogging in turtlenecks; the C-R session drawled out in New York nasal; the “I smoke grass, you know” daughter (another toad variant); the feminist shrink with the severe middle part and a whiff of macramé.

Clayburgh is Erica, a Seven-Sister grad at the very top of her 30s, whose Wall Street husband suddenly ditches her for a girl at a Macy’s counter. She’s still got her middle-class cache — cash, digs, gallery job — but is at a loss about what to do with the rest of her life. Same sentence: “I don’t know who I am without a man.” Like Alice, her solution to that problem is to be with more men. She’s even nabbed a bearded lover, same as Alice — British, porcine Alan Bates rather than Alice’s working-class hero Kris Kristofferson. But how I rationalize preferring Mazursky’s film, when it’s equally as trite but diddles with bourgeois dilemmas rather than the working poor’s tawdrier sprawl, is that girlfriend doesn’t rise to her boyfriend’s ultimatum. At the end of Unmarried, Erica refuses to follow her artist to Vermont. As punishment, he takes leave and saddles her with an enormous painting that she’s forced to heft by herself through city streets. Given his crap art, it’s punishment indeed. Still, there’s something endlessly hopeful about Clayburgh wobbling through early Soho in earth shoes made for walkin’.

More seriously, what these two directors lack, which Vera Drake director Mike Leigh possesses in spades, is a willingness to imagine these characters as truly distinct from their connection to men. Burstyn and Clayburgh do their damnedest to fill in the gaps left by male screenwriters and directors. Burstyn in particular gamely does her generous, wide-lipped best with the plenty-of-nuthin’ that landed in her lap. But Scorsese and Mazursky can’t quite conceive a truly female space for their female protagonists. When abandoned by her husband, Erica is left almost entirely to her own devices; except for one over-earnest, utterly humorless powwow with women we never meet again, no girlfriends rush in to pick up her pieces. Where are those seven sisters when she needs them? And the liveliest scenes in Alice are when Alice and Flo (Diane Ladd) crack each other up while they are sitting in the sun or holed up in the ladies’, but those scenes are few and far between. Relegated to the ladies’ indeed. It speaks volumes that when Alice was reinvented as a sitcom, it focused almost entirely on the relationship between Alice, Flo, and a third waitress, hapless Vera. TV’s less skittish when it comes to las hermanas doin’ it for themselves.

I’m still sorting out why TV does better by women than film often does. For one, it inhabits the same domestic ghetto to which the feminine is still mostly banished — both are literally stuck in the home, where stakes are, if not lower, certainly perceived as less urgent. Typically great directors still don’t bother themselves too much with TV, though cable is certainly changing that. In fact, many of the interesting women directors of the last decade have been resurrecting their careers on shows like The L Word (Rose Troche), Six Feet Under (Lisa Chodolenko), and Sex and the City (Alison Anders).

But many of the best American male film directors continue today to try their hand with the woman in self-recovery. Some, like John Sayles with his Passionfish, succeed more with such material. Most succeed only mildly, if at all. (I regret to remind you of Spike Lee’s Girl 6.) In sooth, short of earning their cub scout “sensitive” badges, I wonder what compels these men to tackle what used to be called women’s films and now are called — I wince as I type the words — chick flicks. Only they’re not called chick flicks when the really big boys direct them. Mike Nichols’ movies, for example, are typically the ultimate chick flicks (see the brittle dirge Wit or, for a real paean to Yuppie careerism, Working Girl) except that no one would deign to call them that, especially at awards ceremonies. Which is fine, anyway, as his women don’t really seem to like other women. Huge mistake. Never trust a woman without women friends, and never trust a movie about a woman’s pilgrimage that doesn’t include her women friends.

Of these big boy directors only Mike Leigh has recently painted a plausible women’s world. Funny that it’s still all about women’s plumbing. One of these days on the silver screen, women in packs will more regularly tread further than the ladies’ room. Excuse me, excuse me. Women’s room.