Just found out essayist Eve Babitz died yesterday. Her singular, obstinate sensuality formed me like no other. I’m beyond bereft.

Just found out essayist Eve Babitz died yesterday. Her singular, obstinate sensuality formed me like no other. I’m beyond bereft.

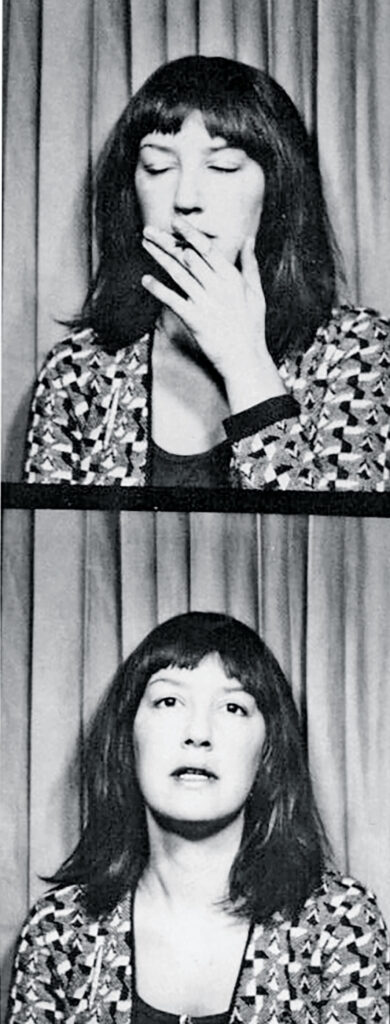

To people in the know, Eve Babitz was the West Coast It Girl of the 1960s and ’70s. Born in May 1943, she marshaled Taurus’ practical magic from the start: Igor Stravinsky was her godfather and Greta Garbo, Bertrand Russell, and Charlie Chaplin, her family friends. A self-proclaimed “groupie-adventuress,” she designed album covers for Linda Ronstadt, the Byrds, and Buffalo Springfield, befriended everyone from Frank Zappa to Salvador Dali, and counted Steve Martin, Jim Morrison, Harrison Ford, and Annie Lebowitz among her many lovers. She was the nude girl in that famous photograph of Marcel DuChamp playing chess, and an extra in Godfather II because, well–why not? But it was as a writer that she shined brightest.

Babitz was living proof that muses could be the sharpest tacks in the room. Her writing was so lush and lean that she made us believe lush and lean were not mutually exclusive. Only Eve could inspire you to buy seven caftans and all the ingredients of a tequila sunrise after reading 10 pages of her book. The cocaine and caviar were optional.

I first discovered Babitz at age 9. Prowling a yard sale, I found a dog-eared copy of her Slow Days Fast Company, and devoured it without grasping a quarter of the references. (Poppers? Ménage à trois? It all sounded delicious.) Her well-read, half-bred, doggedly unwed perceptions imprinted on me, though. Like me, she had a gorgeous shiksa mother and a brainy Jewish dad and like me she rejected “niceness” on the grounds that it precluded too much pleasure and too many good points.

She was my kind of Eve.

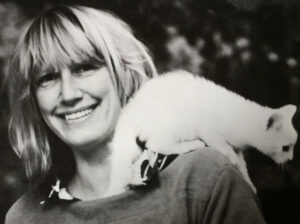

Babitz’s languid self-enchantment and self-reckoning taught me to value my own delight. It’s not that she didn’t value beauty–she worshipped it–but she had no patience for arranging herself to satisfy another’s gaze. In recent years, she’d become more of a recluse but her stubborn magic continued to find self-proclaimed goddaughters like myself. Girls who didn’t want to be chicks so much as broads, girls who wanted to befriend the people they bedded, not wed them. Her words will forever evoke a paradise found, and her faith in authentic pleasure will endure as a treasure map to our own.

Babitz’s languid self-enchantment and self-reckoning taught me to value my own delight. It’s not that she didn’t value beauty–she worshipped it–but she had no patience for arranging herself to satisfy another’s gaze. In recent years, she’d become more of a recluse but her stubborn magic continued to find self-proclaimed goddaughters like myself. Girls who didn’t want to be chicks so much as broads, girls who wanted to befriend the people they bedded, not wed them. Her words will forever evoke a paradise found, and her faith in authentic pleasure will endure as a treasure map to our own.

Please yourself today in the name of Lady Eve.