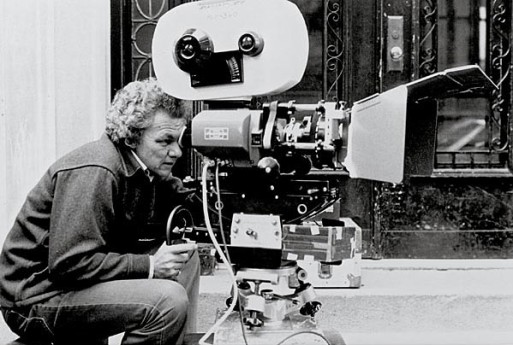

Cinematographer Gordon Willis, the man behind such films as All the President’s Men, Klute, the Godfather triptych and many of Woody Allen’s finest, has become a conscientious objector.

Cinematographer Gordon Willis, the man behind such films as All the President’s Men, Klute, the Godfather triptych and many of Woody Allen’s finest, has become a conscientious objector.

When I mentioned Willis to the only notorious Hollywood insider whom I call my friend, he said, “A bunch of us were wondering the other night if he were still alive.” A quick IMDB search would easily have settled that score, but it also would have revealed that Willis, 74 next week, hasn’t made a film since 1997’s The Devil’s Own. Following a Cinematographers Guild breakfast screening of the The Purple Rose of Cairo last weekend, the DP shed some insight into that disappearance when he submitted to a rather lengthy question-and-answer period for his brothers and sisters.

The Guild had been kind enough to include me in their monthly Saturday morning shindig, their version of the more traditional beery union local picnic. I’ve a soft spot for unions of all sorts, and the cinematographer’s union boys are as good a lot as any. They sit on the arms of each other’s chairs, huddle close when they tell a story, regard each other with unmitigated affection, and somehow all seem alike, regardless of age and gender and race: avuncular with regional accents and bright eyes gleaming behind thick-framed glasses. They seem like family, in other words.

It’s a good scene overall, one certainly worth a temporary exodus from the briny bogs of Cape Cod, where Willis dwells these days. And you can bet the Guild nabs the finest prints possible of whatever film they screen.

Willis looked on from the back of the Tribeca Screening Room while Rose, which has aged into a lovely timelessness, ran. One of my favorite Allen flicks, it features Jeff Daniels as screen actor Gil Shepard who in turn plays Tom Baxter, the pith helmet-clad anthropologist who steps off the screen of a black-and-white Nick and Nora-style romance into the Technicolor Depression-era New Jersey movie theater to woo hapless fan Mia Farrow (who keeps her stammering to a tolerable level here). Less of a metamovie than a lovesick valentine to the transcendent power of ‘30s-era Hollywood glamour, Rose actually carries some of the same wistful contrasts as Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark. But even Allen’s worst films spring more out of magic realism than the drab nihilism that Trier seems to regard as due punishment for those frivolous enough to attend movies, so Rose is infinitely lighter in its loafers — thanks in no small part to Willis’ mastery of the visual understatement.

Afterward, the cinematographer ambled to the front of the room. He has a shock of white hair and watery blue eyes, his confidence and acumen better telegraphed by the tough NYC kid posture and voice that New England hasn’t successfully erased. He speaks easily with colorful metaphors, the way almost all union guys do, whether they be ironworkers or cinematographers. Because of that, and because he’s such a compelling character, I’m including most of his comments verbatim.

About Purple Rose, he said, “We shot the black-and-white movie first, including the characters’ interactions with the people in the theater, and then photographed it again in color stock as it was running in the theater.

“Working with Woody is like working with your hands in your pockets. I would say how I thought something should work and then he would say how something should work and then together we would pound the dough. He shot it with Michael Keaton first and didn’t like the effect so they had to reshoot the first two weeks again. Not as many reshots as you’d think; just embarrassing for Keaton, I’d imagine. Allen has a writer’s mentality but I tried to make it difficult for him to redo things — and it was a film in which it was very hard to redo things.

“To make the black-and-white movie [within the movie], I just picked up the light pattern of ’30s movies and reconstructed it. For the rest of the film, choices were made to minimize color. Everything in the movie was sets except for the theater exterior, which was in Piermont, NJ. The interior of the theater was a real porn house in Brooklyn.” [Because this fact was not greeted with loud guffaws and whistles, at this point it became obvious this wasn’t a typical union.]

Willis moved into the health of movies, past and present. He’s not a big fan of technology for the sake of technology. “Zooms are lazy closeups. And too many people hang their hats on video assist; it’s a way to avoid too much. Video assist helps people dissociate from the scene that they are directing. Pretty soon the director will be directing all the way from his apartment.

“Coppola and Beatty got very into it. Frances used VA from his trailer and then a speaker to communicate with the actors,” he noted with a dry grin. “But I wouldn’t suck on that tube all day long. The truth is that video assist will always show you something different than what you throw on the screen. I used it for tech check and stunts only.”

Or: “Anamorphic [widescreen technology, in uber laymen terms] is in vogue right now. The smaller the indie movie, the more anamorphic. Back when I did The Paper Chase, I told Fox to do it anamorphic. Their response — and keep in mind Fox invented anamorphic — was ‘It’s not a Western.’ Like everything else, it’s how you use the format. Any idea in this business is like poison gas in a room. I liked how they used it better in the ’70s than how they do now.

Another cinematographer said, “Labs are laundromats now, so how you do get repeatability these days?”

Willis’ response was succinct: “I wouldn’t know; I haven’t done a movie for six years. Last time, the lab tried to help me but there was blood over all the walls. Working on The Devil’s Own I knew you get sick if you try to fix everything for everyone. [Note: According to IMDB, eight years have elapsed since The Devil’s Own was released.]

“When doing the Godfather movies, I had trouble with continuity, of course. Decades passed between making II and III, for example. I used brassy, burnt yellow a lot. The only problem with III besides it not being a very good movie is that it used a different technique. Super 185 to blow into 70 mm. I didn’t care for that, but Francis did…”

GW is very nuts and bolts. When asked how he developed as a cinematographer, he responded: “My wife was pregnant and I needed some money.” You both believe him and you don’t — he’s utilitarian but also clearly takes pride in doing his job well.

“Who mentored me? I guess not too many people. I did what I liked. I learned from watching at first, sure. You have to learn how to cut if you’re going to learn how to shoot well. Then I pushed through what everyone else was doing and thought I should be doing, and I did what I wanted. I was very specific about what I should do. In concert, it’s luck but it’s also always your attitude.

“A director would walk around for two days trying to sort out how a shot should look and I would just say in two minutes,’I think it should be this way.’ ”

Not shockingly, Willis is an enormous proponent of less is more. “I spent a lot of time on films taking things out. Art directors would get very cross with me. If something’s not going well, my impulse is to minimalize. The impulse of most people when something’s not going well is to add — too many colors, too many items on a screen, too many lights. If you’re not careful, you’re lighting the lighting. American films are overlit compared to European ones. I like closeups shadowy, in profile — which they never do these days.

“People by nature like complexity and rarely recognize the elegance of simplicity. I like simplicity. So I just do it. I figure out what you have to say in this scene and how it connects to the last and to the next and then shoot. Today they do what I call dumpster directing. They shoot too many angles in scenes. Two problems result: 1. It tires out the actors. 2. The editor ends up making the movie, since there’s no true point of view if you shoot it every which way.

“What’s needed is simple symmetry, but everyone wants massive coverage these days because they don’t have enough confidence in their work and there are way too many cooks in the kitchen.

“My philosophy has always been that it should look easy even if it’s hard to make.“

Someone asked him about a piece of Local 644 folklore and with a mix of chagrin and some residual pride, he said:

“Yes, it’s true. I threw a camera out on the street once during the shoot. The thing had broken three times, and each time they fixed it just well enough to get it running again but not enough for it to not break again. It’s a common mindset. And I’m not the type to fetishize a camera. I always say that ideally, something would have French design and German make. Because then it would work.

“Finally, I just got fed up. Each time it held up production. I threw it out, yes. You can believe the next camera they sent over was perfect. Well. I like stuff that works.”

Since not enough seems to work these days, Willis is for all practical purposes retired. He seems to think the industry and the world are in such dire straits that he’d prefer not to be actively involved. I talked with him alone afterward at the guild luncheon and he said he worries a lot about the world that his children, and all younger people, are inheriting.

Then, he seemed less gruff than sad. Sad and unfailingly kind.