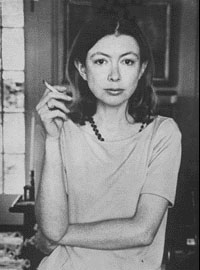

Broken English is the exact sort of film that gets lost in the Sundance shuffle. About a sadsack 30something single wiling her days in a nearly there New York existence (she works a chi-chi downtown hotel job rather than the art world gig she’d desired; befriends rather than belongs to a prosperous gorgeous couple), its premise falls in with the listless fare that comprises festival dockets these days. Not to mention that it stars lil Miss Indie America herself — Parker Posey, who acrobatically jumped her own shark nearly half a decade ago in a drift of tiny ironies masquerading as movies.

Anyone who’s read this blog over the last few years knows of my mounting frustration with the American independent film scene. Why I reserve my ire for this world rather than Hollywood is simple: I refuse to play frog to the scorpio of the major studio system. Complaining that a major motion picture is crap is pretty much like whining that Twinkies don’t yield nutritional value. The studio system is predicated on a business model in which the value of individual films is calculated on how much money they produce, plain and simple: if the studio doesn’t anticipate a film will make money, it doesn’t make it. And if it anticipates that it will make money, made it shall be — even if the script is riddled with holes, the stars are radically miscast, and the editing is as junky as the guys huddled on my corner. That the financial worth of these movies is predicated to some degree on people’s experiential (or anticipated) pleasure is the only place where aesthetic or social value enters this picture, ultimately, even if the associated cogs –the directors, the actors, cinematographers, editors, what have you—still care fiercely about the quality of the work they are producing for financially unrelated reasons. So a feature that boasts strong pacing and visual style — Ocean’s Thirteen, for example — is preferable for everyone. It will last longer on the shelf due to good word of mouth; it will be more fun to plunk cash down to see.

And, let’s face it, even if their only job is to entertain plain and simple, often those big Hollywood blockbusters do their job better than American indies do. Spiderman 3 may have been an inky, nasty clot of conceits and plotlines, but its predecessors provided great fun that snatched you right out of your mishegos for a solid two hours with great wit and color. The films with greater pretenses are harder to bear, obviously; those hardheaded bids for Oscar validation that glut the cineplexes as the end of each year approaches. I pretty much hate them all—the biopics, the Spielberg Serious Ventures (with the exception of Munich, which I didn’t mind for all its bumpiness), the war porns—but so does everyone, including the Academy, which is why they less and less frequently get made. All Hollywood does really well these days is Dissociation Junction: blockbuster action movie and the occasional romance (in which clothes and posh interiors usually star) and gross-out, no-schmabortion comedies. God love them all. A waste of money, but a fun waste: our country right now, in other words, for better but mostly worse.

For if Hollywood reflects America’s unchecked capitalist impulse, the state of US indies reflects our enormous identity crisis in its wake. We are a country at war but rarely acknowledge it except to make a point at someone else’s expense. We discuss how we are systematically decimating our environment while we swig from tiny disposable plastic bottles and veer SUVs down our ever-increasing highways. No one fully cops to how wide the gap between rich and poor grows daily because everyone on both sides of that great divide might judge themselves unfavorably. Not to mention: We barely educate our young. We sicken and die of the worst kind of diseases overly developed societies have to offer (diabetes, cancer, lifestyle-related heart disease). And we live under the most corrupt, mendacious regime that this country has ever known. By many counts, we didn’t even elect it in — yet another sign that our democracy has grown largely theoretical. That we don’t storm the White House and completely revolt speaks not only to our addiction to comfort and the illusion of stability but to our profound levels of dissociation. Levels that Hollywood plays a large part in ratcheting up.

God love it.

None of this is news, not in the slightest. I am either preaching to the choir or to deaf ears, and either way the question is she breaks nearly nine months of silence for this kneejerk song and dance?

And my answer is, yes, yes, yes. Because these facts are wildly relevant to the state of independent film. An institution I still care about and, more to the point, deeply need, but one that has proven as dysfunctional as most of the other deep loves of my life. For how do you make conscious film, film presumably made for other reasons besides profit and resume-building, in this environment? If it’s true that art is only as healthy as its culture, and I truly believe that it is, then independent film, the art made in some way to illuminate the human condition or to celebrate it or at least remind us that we are human, is bound to suffer. And it has.

To be fair, many filmmakers are trying. It’s just that their efforts show, and I resent being bombarded by the seams of a filmmaker’ intentions — no matter how earnest they are. Truly, most indie fare these days suffers from overearnestness of one ilk or another. There are the Sayles babies, who attempt to solve or at least tackle all the world’s problems in one swell foop. Even those ventures that are banging in theory still go down like medicine that could use a spoonful of sugar. Then there are the many indie filmmakers content to merely approach their own problems via the medium of film. Admittedly, this self-searching, however initially masturbatory, has served as the chief impetus of most art since the beginning of time. (As a certain someone has been known to say: “now you’re going to start knocking my hobbies?”) But there’s a difference between, say, Noah Baumbach, who dresses his 90-minute therapy session (Squid and the Whale) in early 80s nostalgia rather than in any greater relevance, and European film, which philosophizes about human emotion rather than wallows it. So much of American indie that doesn’t labor to wake us with dirty buckets of cold water — clunky ventures such as Fast Food Nation or, oy, The Situation — languishes instead inside the grime of a writer-director’s navel, albeit one charmingly or whimsically adorned.

But.

But I still believe movies satiate very primal longings in this crazy constructed modern world we call home these days — call it the desire to be understood; the need, ideally fulfilled in meditation or prayer, to surrender to your problems from a healthy remove in order to more thoroughly comprehend them; and the need to connect those problems to someone else’s, to many else’s. Boys, and some girls, who never cry in their real life sob unabashedly at the movies. Girls, and some boys, sneak into romances or, you should pardon the expression, chickflicks when our own love lives come tumbling down round our ears. It’s why the only moderately talented Sandra Bullock radiates such great appeal. She willingly swings us and all of our problems, be they loneliness or addiction or rampant immaturity, over her shoulder in an emotional rucksack as she embarks on often surprisingly successful pilgrimages for redemption.

Ideally, films connect us back to our authentic selves rather than our mere egos via a painless honesty typically only achieved through drugs or spiritual transcendence. But that’s because film is a drug and movie theaters are our temples. Where else can you at least expect so many varied humans to sit in rapt silence for hours on end these days? Where else can you hope in this ruptured dream that we call the US that we might commune with both beauty and truth shoulder to shoulder with strangers and loved ones alike?

Admittedly, it’s a lofty way to regard film. But (and here’s the real but) why not? Why can’t the films purportedly not solely made for profit aspire to be art? Art that does not merely proscribe our wretched existences but prescribe a little insight even it’s merely insight into our what’s breaking each of our hearts? And why not expect such films to entertain as well as to illuminate? As Edmund White once wrote, “What I really like in art is entertainment, if what is being entertained is the mind as well as the parts of the spirit and body that can register pleasure.”

So on said admittedly lofty note I wind myself back to the example of the little-indie-that-barely-did: Broken English. In the face of all the solitude that has proven to be the ides of my 30s, the hard questions that being alone raises amongst the Noah’s Arks coasting in my New York sea, I can recognize myself in this film without hating Posey-as-protagonist or even me in absentia. Posey for once has less channeled her bratty deadpan than offered herself up as a cracked, dusty mirror that’s beautiful in all of its flaws.

Small but not small-minded, linear but not leadfooted, herein lies a film that channels an American optimism grounded out by a European ability to withstand personal misery. In fact, the film is bighearted in its acceptance of misery, important in its insistence that misery doesn’t always require company in order to be ameliorated, political in its suggestion that coupledom is so often a placebo. And that often true solutions only appear when we’ve settled into their absence.

I knew at the critics’ screening that this film largely would falter in reviewers’ eyes. It’s not perfect by any stretch of the imagination; its pacing at time devolves from graceful ambling to downright choppy. But it faltered because it’s not about people who’ve fallen through the cracks grandly nor is it about the critic-by-proxy nor is it about the odds-beaters (though the ending is for sure a gimmee). It’s about a wildly condescended-to demographic: the single woman, and Zoe Cassavetes, who knows of what she writes/directs, attempts to articulate that existence with more low-key dignity than sturm und drang and soundtrack cues and lascivious winks. I contend that lady indie filmmaker did her job well. A fact, in this current environment, that is worth noting. Trumpeting even. Like this.