(This is the second installment of a long project that I’ve decided to post here. As always, dear Sirenaders, do with it what you will. Comments are especially welcome as it’s a work in progress and I’d appreciate the postcard from beyond the abyss.)

I was saved by the doorbell, which began ringing and ringing and, within 15 minutes, had produced such a stream of multihued and platform-shoed people that they filled the entire brownstone. It being 90s Brooklyn and she an apparent trustafarian it turned out the couple owned the whole building, which they’d painted an unfortunate and very unlikely pink, and laden with room after room of inconspicuously expensive artifacts of high bohemia. African statues and exotically threaded rugs and a sound system to break your heart.

I flattened myself against one wall, gripped my seltzer, and watched these Brooklyn kids with big hair breathe each other’s big air. Though he’d been edgier when I’d first met him in college, The WASP had grown stuffy after we’d moved to New York. Our social life had consisted of dinner parties and openings with slightly older couples, gay and straight, who’d invariably ask me, “Now, what is it that you do?” It was a question I’d found intolerable ever since we’d moved in together, and I’d never known what to say. The honest answer would have been “look pretty, be quotable,” but even I knew I wasn’t supposed to be that quotable. The truth was I’d spent most days walking city block after city block, mawing an increasingly virtuous diet as my plaguing symptoms mounted, reading whole novels without buying them in bookstores, practicing yoga at the ashram around the corner, and waiting for the WASP to come home from work. So to these slickly packaged architects and magazine writers and dotcommers—o relics of that cushier time—I’d merely smile brightly and, no joke, let him answer for me (“this one’s a rock star in the making”) as he slung a long tan arm around my shoulder.

I’d forgotten what it was even like to be around people my own age, people who didn’t necessarily know what they wanted to be when they grew up and were visibly digging the process of figuring it out. As I watched them dance I tried to write them off as wannabe bohos but in my experience such types never moved like they knew how to fuck. And these kids were actually getting down, enlisting hips and pelvis and booty in every move as hip hop pounded throughout the house. None of that high-strung, high-shouldered bobbing I’d resigned myself to in the Manhattan crowds I’d been running in over the last few years. And everyone was decked out in colors—bright, head-turning pastels and royal primaries.

Like so many at the time, I’d retreated behind a funereal palette and so was wearing slim black cigarette pants and a white oxford shirt. Wired gold glasses even, with small pearl earrings and my standard dirty blond bob. Next to these kids I felt as stodgy as I’d considered the WASP to be. Male and female, they were decked out in overalls and clogs and Mary Janes and combat boots and drooping Levis and Mexican wedding shirts and dashikis and stripes and big polka dots and knee socks pulled over fishnets with tiny skirts and shorts and huge chinos and midriff-bearing tees even though it was mid-winter. They all seemed to know each other and were chattering in that rapid hyphenation of public intellectualese and high and low cultural references (Freud meets Frankie Goes to Hollywood) that has since faded in the long shadow of the emoticon.

Since I’ve never smoked and knew no one there I did what I always did back then when I got nervous: I eye-fucked strangers, less to actually get laid than to gauge my appeal as well as to draw someone into conversation. It worked well enough, partly because of the glow I’d recently been radiating but mostly because my mysterious ailments had left me with a gaunt awkwardness that was no joke. The last month had taught me all about the attraction men felt for drowning kittens-in-emaciated-female packages. Before I knew it, I was surrounded by a group of nice enough guys who kept fetching me seltzers and introducing me to more of their friends. One was feigning a fascination with my limited beverage predilections—“You don’t even like orange juice?”—when the lady of the house finally sidled up to me. “You’ve certainly met the men at this party,” she said, not entirely nicely, and I saw that she was a woman who disliked most other women even as she complained about not having female friends.

“I didn’t really get introduced to the guy playing chess earlier,” I said casually, and she laughed. “Oh, all the girls go bananas for him. He’s a painter who lives over in Williamsburg in a factory building he redid.”

I perked up. That was the kind of NYC glamour I’d been missing out on during my years of hiding behind the WASP.

“Don’t get misled by that choir boy vibe,” she said. “He’s a heartbreaker.” I eyed him, all Marky Mark moves and muscles, grinding up against a really tall girl with a flame-colored afro and a poncho. Some choir boy. I’d never slept with someone I’d didn’t think I could love before, and I knew I could never love anyone unsubtle enough to develop a reputation as a heartbreaker. An ideal candidate for my first fast fling.

Just then a tall dark drink of water entered the room and immediately started getting up on the girl from behind, herding the couple into bigger and bigger moves, sandwich style, until all three of them fell on the floor laughing, limbs akimbo. When he saw me laughing too he said to my painter: “Who’s the girl?”

“Her? That’s my future wife.”

Which is how I met the man destined to become The Artist Formerly Known as My Boyfriend.

“Love is also a good subject, as you might be said to have discovered.”–Ernest Hemingway, in a letter to Scott Fitzgerald, 1925

The following Saturday night was our first date, and I was a full-on crazy lady in the days leading up to it. Not because I feared he wouldn’t live up to my impression of him but because I knew that he would. Before leaving the party the weekend before, I’d sat quietly in a smaller room in which he was holding court. Watching him tell bad jokes—I deemed all jokes bad since designated joke-telling the lowest form of humor next to stand-up comedy—I realized he was the least ironic person I’d met since grade school, a fact that endeared him to me dangerously. As did the fact that I would have picked out every album he dropped on the ’70s turntable—Al Green, Chaka Khan, even early Hall & Oates, a preference everyone in my life misunderstood as kitsch-borne.

When I finally extricated myself to find my coat in the front hall, he appeared next to me. Though he’d ignored me while I’d been watching him for the last hour, I’d felt he was aware of my presence. Now I knew I was right.

“How can you be leaving already?” he’d said with no inflection, a trait I was to learn was characteristic of him.

“Better to leave them wanting more,” I’d said, and blinked at my own ridiculousness.

He’d soldiered on. “You can’t leave without me knowing whether we’ll see each other again,” he’d said and pulled a gallery opening invite out of his pocket. “Write your number on this.”

I’d thought while he looked for a pen in his pocket. Since things had ended with the WASP, I’d only taken other people’s numbers, a policy that seemed wise given the terrifying NYC dating scene. But taking a girl’s number was a big part of any heartbreaker’s shtick, and this guy seemed to need his shtick. If I was going to get to sleep with him, it was clear I had to play along. I pulled a pen out of my own bag and wrote down my number.

“What’s your last name?” he asked gravely, so I wrote my full name down too, underlining the one “s” in my last name.

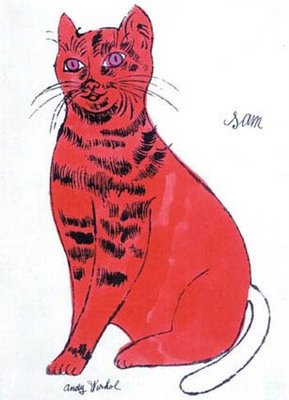

“People are always giving me an extra S,” I’d explained, handing the paper back to him. He accepted it slowly, and in one deliberate motion, had moved in just as slowly to kiss me. Later, when I watched him extend an invitation to our newly rescued kitties, I recognized the same strategy. He performed the action so quietly and steadily that we skittish animals felt contact was our idea rather than his. Certainly it was the best kiss I’d had in a long time, if not exactly the unspoken conversation that kisses had been with my very first love. But that guy was the kind of heartbreaker I planned never to succumb to again, the sort who smelled of cloves and the woods between our houses and a little bit of my sweat mixed up in his. This guy smelled, I’d realized slightly hysterically, of Obsession perfume and turpentine and commercial hair gel. It was about as unlikely a scent as I could have imagined in a suitor six months ago. Which confirmed he was ideal.

At four that morning, the phone had rang. I listened in the dark, body taut, to his message. “I am hoping you got home safely,” he began, without bothering to introduce himself and with a curious circumvention of contractions. “I am very glad to have met you, and am hoping you will come bowling with me next Saturday. As a date. If you come, I promise I will never, ever give you an extra S.”

Despite myself, I was thrilled.