Ready for the thing no one ever says? I like my body better at 50 than I did at 20. It’s not perfect now but it wasn’t perfect then. In general bodies aren’t perfect. Bodies are encasements, temples, tactics. Precious and purposeful. Us. At 20 I was sick, scared, anxious, angry–anorectic, with the colon and joints of a much older woman due to two decades of sustained and displaced trauma. Aka hysterical in the classic Freudian sense. (Fuck Freud, obviously.) I panicked over every extra calorie and drew what little self-esteem I had from being thinner than others–no one acknowledges what mean girls we anorexics can be. At 50 I am all curves and angles–fully inhabiting the Scottish-Sioux-Ashkenazi peasant body that is my birthright. Big hands, breasts, hips, belly, brain. Fierce look, limbs, will. Strong as a mother, o yes, and perfectly willing to flirt with whomever stares because at this point no one can topple me with their desire. I’m like a red oak that way (every way). Are my eyes going? For sure. Is my back worse? Doubly sure. But every day I feed this body beautiful useful things. I stretch it, walk it, water it, sun it, shower it. Lipstick it. Listen to it. Love it. In return it still holds me up and sometimes even lets me shine. At 50 I am old enough to be grateful for every day and every way I feel physically good–for every organ, muscle, inch that works well. For every ailment that heals. Even better, I have learned how to be grateful for change–even decay–because it means I’ve lived long enough for it to happen. At 50 you don’t look like anyone’s projection anymore, no one’s generic dream of a girl or a perfect lady. But you’re not really invisible. Instead, you look like the life you’ve led. What’s more beautiful than that?

Ready for the thing no one ever says? I like my body better at 50 than I did at 20. It’s not perfect now but it wasn’t perfect then. In general bodies aren’t perfect. Bodies are encasements, temples, tactics. Precious and purposeful. Us. At 20 I was sick, scared, anxious, angry–anorectic, with the colon and joints of a much older woman due to two decades of sustained and displaced trauma. Aka hysterical in the classic Freudian sense. (Fuck Freud, obviously.) I panicked over every extra calorie and drew what little self-esteem I had from being thinner than others–no one acknowledges what mean girls we anorexics can be. At 50 I am all curves and angles–fully inhabiting the Scottish-Sioux-Ashkenazi peasant body that is my birthright. Big hands, breasts, hips, belly, brain. Fierce look, limbs, will. Strong as a mother, o yes, and perfectly willing to flirt with whomever stares because at this point no one can topple me with their desire. I’m like a red oak that way (every way). Are my eyes going? For sure. Is my back worse? Doubly sure. But every day I feed this body beautiful useful things. I stretch it, walk it, water it, sun it, shower it. Lipstick it. Listen to it. Love it. In return it still holds me up and sometimes even lets me shine. At 50 I am old enough to be grateful for every day and every way I feel physically good–for every organ, muscle, inch that works well. For every ailment that heals. Even better, I have learned how to be grateful for change–even decay–because it means I’ve lived long enough for it to happen. At 50 you don’t look like anyone’s projection anymore, no one’s generic dream of a girl or a perfect lady. But you’re not really invisible. Instead, you look like the life you’ve led. What’s more beautiful than that?

Archive | Style Matters

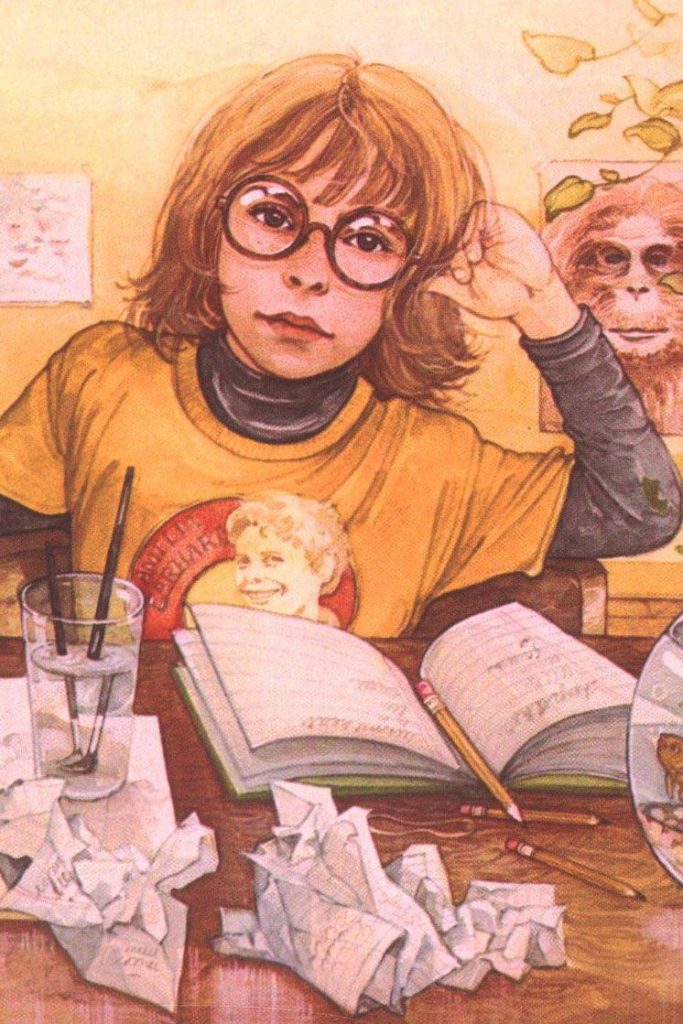

Painting at Audre’s: Part I

Once when I was 9, a mother and her two kids disappeared from our neighborhood. It wasn’t a kidnapping. It was just that for years they lived down the street from our house, then one day they were gone.

Once when I was 9, a mother and her two kids disappeared from our neighborhood. It wasn’t a kidnapping. It was just that for years they lived down the street from our house, then one day they were gone.

The husband was still there, but when my mom took my sister and I around to visit his wife and kids, he said they were out. His normally polished appearance was unruly—clothes rumpled, face unshaven—but he offered no further explanations and shut the door before my mother could ask any more questions. When we went back the next day, he didn’t answer the door, though his orange Volvo was parked in the driveway. Nor did he answer it the day after that.

For a full week my mom kept finding reasons to drop by. A cutting from her favorite fern, an invitation to take all the kids to the park, cookies she’d just baked, a mug that seemed up the wife’s alley. My mother liked to collect things for people, like a mother bird dragging treasures back to her chicks safe in their nest.

But no matter what time of day we stopped over, no one ever answered the door. The orange Volvo was always there, each day covered with more leaves, but the mother’s car never reappeared.

The real reason my mother kept looking for this woman is she was one of the few people in our neighborhood whom my mother liked. Having spent her young adulthood in downtown Boston, she’d never cottoned to the suburban town to which my parents moved after I was born. She never said it directly—my mother said almost nothing directly—but even as a kid I could tell she found the other mothers in our neighborhood grating or phony or both. She relaxed around this woman–told jokes, pulled faces, lingered over coffee.

I liked this woman too. Let’s call her Audre, because it’s close to her real name and she possessed the practical, large-hearted lyricism of Audre Lorde, whom she liked a lot.

Back home we spent a lot of time wondering where Audre might have gone. Was she sick, I wondered. Does she not like me anymore, wondered my mother. It was my father, surprisingly, who came up with the right answer.

Maybe she left her husband, he said. Continue Reading →

Redgrave as Metaphor

What happens when a materialist film critic has an anxiety dream:

What happens when a materialist film critic has an anxiety dream:

Shoes—shoes lost, shoes gained, shoes lost. I’ve lost my own and don’t have another pair with which to safely exit this terrible claustrophobic party thrown by a celeb hostess in a gentrified section of Brooklyn. Others (the hostess’s assistant!) keep stealing my original pair, bringing me five more pairs that are impeccably beautiful and whisking them away as soon I get ensnared in another vapid starfucker conversation. We’re talking perfectly soft and shined loafers and boots by Prada, Miu Miu, Marc Jacobs, Louboutin—God, labels seem so pre-Covid. I find myself longing for such refined empty luxury.

Vanessa Redgrave—even longer and blonder and more displeased than she seems on screen—turns out to be the hostess. Grand-dame sociopathy masquerading as cool calm collection. She sweeps and droops around, getting drunker and drunker on perfectly rendered martinis–lemon not olive–as her guests wax and wane. At one point there are people crammed into every corner of her too-white house. Someone does the math and declares it 2012 guests, which is a 1:1 ratio for every square inch of the living room. White furniture white rugs white walls white chandeliers. Her house is hoarder-stuffed but with the most beautiful things: Chagall paintings and Brancusi sculptures and 70s Dior so it’s hard to register the same disdain as if it were plastic angels from Home Shopping Club. More a mixture of envy and disgust and judgment that I meta-judge within myself. I feel as if I’m a poor kid in Newton again. I’m stuck because, oy, no shoes so end up sleeping on a very white couch, my red lipstick leaving a crime scene on a cushion. Continue Reading →