In Subway Veritas

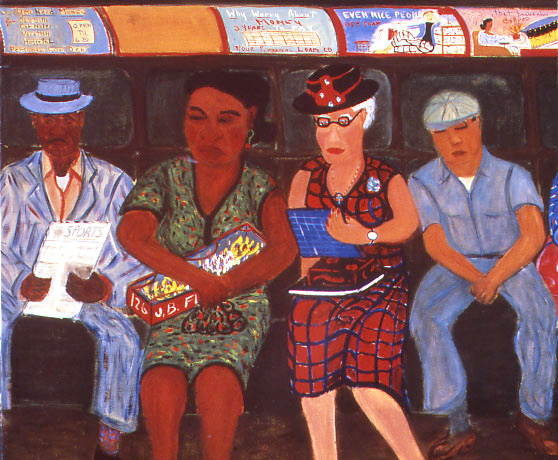

It was another day of dodging zombies who weren’t looking at anything but their smartphones. NYC contains so many sorts of people—so many people, period–that it requires a strict adherence to the social contract in order to remain livable. We don’t need to be nice here; we need to be reasonable. Stay to the right side of a busy sidewalk. Don’t cut in line. Look where you are going. Keep your private conversations private. Let people exit a subway car before you enter it. Throw your trash in a trash can. The zombies (I’d call them smartphonies but they’re just too dumb) do not heed these seemingly intuitive rules of conduct, which makes it hard not to treat them like zombies. And that’s too bad because this finely feathered city is always so much more pleasurable when we marvel over each other’s humanity. I try, this Mz. Manners always tries, but today was already trying: swampy, scratchy, red-tape-y, with a thin wire of metallic dread threading through everything. (I am still generally overcome.) By tonight’s subway ride, I felt an unspeakable tenderness for few who were sitting quietly with paper books or, better yet, their own thoughts. I won’t say what I felt for the slack-jawed manchild, legs spread so wide that he took up two seats by himself, who was playing a videogame on his Samsung Galaxy while a frail-looking older woman teetered in his direct field of vision. I really won’t say how I shamed him into giving up his seat for her. But I will say that casual unkindness hurts my heart so much.

It was another day of dodging zombies who weren’t looking at anything but their smartphones. NYC contains so many sorts of people—so many people, period–that it requires a strict adherence to the social contract in order to remain livable. We don’t need to be nice here; we need to be reasonable. Stay to the right side of a busy sidewalk. Don’t cut in line. Look where you are going. Keep your private conversations private. Let people exit a subway car before you enter it. Throw your trash in a trash can. The zombies (I’d call them smartphonies but they’re just too dumb) do not heed these seemingly intuitive rules of conduct, which makes it hard not to treat them like zombies. And that’s too bad because this finely feathered city is always so much more pleasurable when we marvel over each other’s humanity. I try, this Mz. Manners always tries, but today was already trying: swampy, scratchy, red-tape-y, with a thin wire of metallic dread threading through everything. (I am still generally overcome.) By tonight’s subway ride, I felt an unspeakable tenderness for few who were sitting quietly with paper books or, better yet, their own thoughts. I won’t say what I felt for the slack-jawed manchild, legs spread so wide that he took up two seats by himself, who was playing a videogame on his Samsung Galaxy while a frail-looking older woman teetered in his direct field of vision. I really won’t say how I shamed him into giving up his seat for her. But I will say that casual unkindness hurts my heart so much.

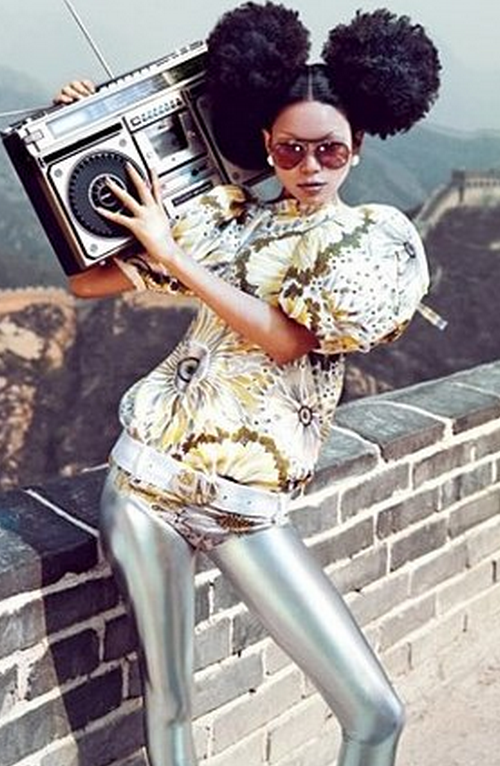

Take a Bite Out of This Crazy Apple

Crossing Williamsburg’s Meeker Ave at Metropolitan last night, I looked around for a cop. There’s always one lurking at that corner since there’s so much precarious traffic pouring in from the Brooklyn Queens Expressway and the Williamsburg Bridge. Sure enough, I spotted a patrol car lurking beneath the underpass and stopped before walking against the light: The police have been super into handing out jaywalking tickets lately. Just then a cab came hurtling toward the intersection at approximately 800 mph, hooking an illegal left at the light and nearly swiping a bearded boy on a Vespa in the process. The “don’t walk” sign still lit, I sailed into the street, grinning at the cop as he pulled out past me, siren already wailing. Sorry, NYC’s Finest, but this isn’t Portland. The residents of this city will always give you bigger fish to fry than poky ole pedestrians.

Crossing Williamsburg’s Meeker Ave at Metropolitan last night, I looked around for a cop. There’s always one lurking at that corner since there’s so much precarious traffic pouring in from the Brooklyn Queens Expressway and the Williamsburg Bridge. Sure enough, I spotted a patrol car lurking beneath the underpass and stopped before walking against the light: The police have been super into handing out jaywalking tickets lately. Just then a cab came hurtling toward the intersection at approximately 800 mph, hooking an illegal left at the light and nearly swiping a bearded boy on a Vespa in the process. The “don’t walk” sign still lit, I sailed into the street, grinning at the cop as he pulled out past me, siren already wailing. Sorry, NYC’s Finest, but this isn’t Portland. The residents of this city will always give you bigger fish to fry than poky ole pedestrians.

The Bold, Biblical Agenda of ‘Calvary’

Calvary begins with a close-up of a priest in a confession booth. “I was seven years old when I first tasted semen,” an off-screen voice announces. “Certainly a startling opening line,” the priest (Brendan Gleeson), who is known as Father James, responds. We could say the same of this film, which boldly lays out its agenda – witness its name, after all – not to convert us so much as to incite us to ponder our own agendas instead.

Calvary begins with a close-up of a priest in a confession booth. “I was seven years old when I first tasted semen,” an off-screen voice announces. “Certainly a startling opening line,” the priest (Brendan Gleeson), who is known as Father James, responds. We could say the same of this film, which boldly lays out its agenda – witness its name, after all – not to convert us so much as to incite us to ponder our own agendas instead.

The unnamed voice goes on to say that, in a week, he will kill Father James because he is not a malfeasant like the priest who sexually abused him for years: The death of a “good priest” will make a statement. Cards thus on the table, James is left to sort out his affairs as well as the identity of his would-be killer. Consider this as a pre-crime procedural, then (the press notes describe it as a “who’s-gunna-do-it”)–one that is so formally constructed that we may surrender to James’ soul-searching in both senses of that term.

If all this sounds awfully literary – a sort of Swedish mystery set afire with ancient Irish angst – that’s not a coincidence. At a recent Q&A at The Museum of the Moving Image, writer/director John Michael McDonagh described himself as a “failed novelist.” But while many films of such portent might benefit from being a book instead, Calvary is ideal in its current medium. Its claustrophobic interiors, contrasted with the surf and sky of the Irish sea town where it is set, wordlessly remind us of the harsh beauty and isolation that is the human condition. And that world beyond words, the one that exists beneath the nattering of daily life, better evokes the divine experience, which is precisely what this film invites us to ponder during its 100 minutes. Continue Reading →