The Church of Signs and Sirens: Ladybug

En route to the coffee shop at 7 am today I was feeling fine. Unfettered by the longing I always carry and rarely articulate. It was cool and grey, my favorite sort of summer morning this year. I was wearing a dress with pockets so deep they could store everything necessary for my jaunt—keys, wallet, lipstick—which left me free to swing both arms and legs as I strode. I’d slept the night before in braids, and my hair, only recently grown out enough to be considered really long, swung too, and in the rippling mermaid waves I’d always hoped they would. All in all, it was as if a crease had been folded in the time-space continuum and my hopeful 7-year-old self had temporarily been granted control of my grown-up body. Once again I was the girl who’d never had her heart broken, not even by her daddy. The girl who remembered all her magic. It felt great, though I hoped she liked coffee as much as I do.

En route to the coffee shop at 7 am today I was feeling fine. Unfettered by the longing I always carry and rarely articulate. It was cool and grey, my favorite sort of summer morning this year. I was wearing a dress with pockets so deep they could store everything necessary for my jaunt—keys, wallet, lipstick—which left me free to swing both arms and legs as I strode. I’d slept the night before in braids, and my hair, only recently grown out enough to be considered really long, swung too, and in the rippling mermaid waves I’d always hoped they would. All in all, it was as if a crease had been folded in the time-space continuum and my hopeful 7-year-old self had temporarily been granted control of my grown-up body. Once again I was the girl who’d never had her heart broken, not even by her daddy. The girl who remembered all her magic. It felt great, though I hoped she liked coffee as much as I do.

I wasn’t wearing my glasses since at 7 I didn’t need them and in general I always find it relaxing to be liberated from too many details. But my nearsightedness worked against me when a man began sprinting down the other side of the street. He was copper-colored with close-cropped hair and, as he ran closer, I could see how elegantly the muscles in his limbs and shoulders tapered though I still couldn’t see his face. I saw that he was wielding a slightly forlorn bouquet of flowers, the sort you buy at the deli in a last-minute rush of love or forgive-me-baby. I saw too his bald spot, large enough that most men would have shaved their whole head in order to make that baldness seem deliberate rather than a vulnerability. It was the last detail that got me. I had always found that bald spot painfully endearing in my last big love, a man I’d once been sure was no less than my destiny, my heart, my reward for all that had come before. All that jazz. Continue Reading →

L’avventura and a New York Summer, Naturally

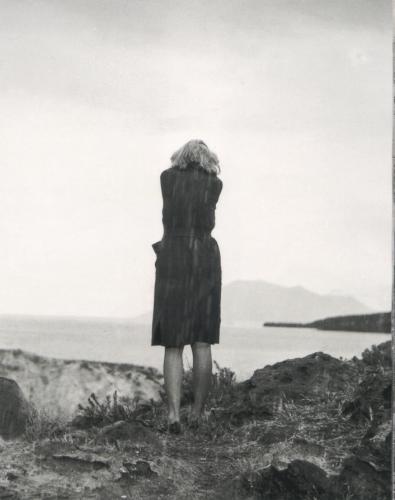

I spent two of yesterday’s most sweltering hours at New York City’s Film Forum, transported to the big black-and-white glamour of L’avventura, Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1960 travelogue. Many of my colleagues swoon over this film’s contribution to film grammar, its exploration of the myriad faces of love, and they’re right to do so. I sat amongst some of them yesterday and their faces looked uncharacteristically sweet, even innocent, as they watched, rapt, in that screening room. That innocence is part of why I gladly, worshipfully surrender to the Italian director’s films again and again, especially in summer. In his still and silent and perfectly framed worlds dwell the purest respite I know outside of actual nature.

I spent two of yesterday’s most sweltering hours at New York City’s Film Forum, transported to the big black-and-white glamour of L’avventura, Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1960 travelogue. Many of my colleagues swoon over this film’s contribution to film grammar, its exploration of the myriad faces of love, and they’re right to do so. I sat amongst some of them yesterday and their faces looked uncharacteristically sweet, even innocent, as they watched, rapt, in that screening room. That innocence is part of why I gladly, worshipfully surrender to the Italian director’s films again and again, especially in summer. In his still and silent and perfectly framed worlds dwell the purest respite I know outside of actual nature.

For Antonioni’s films almost—almost—compensate for the terrible swamp that New York invariably becomes every summer. I know many who sing New York summers’ praises, and when I was young I was one of them. To people’s complaints that they missed nature in New York, I’d reply that in New York we humans were the nature. I still think that’s true. Bumping against each other with virtually no personal space, we prowl about, sniffing each other’s butts, brandishing our feathers and guarding our turf as fiercely as any beast in the wild. If our jungle happens to be concrete, what of it?

But every year I feel less charmed by the gorgeous mistakes we New Yorkers tend to make in our unbearably hot summers—by our flaring passions, our sticky bodies, our business exposed every which way. I long instead for the one thing that’s hard to order up in this crazy apple unless you’re on a billionaire’s budget: quiet. A silence, uninterrupted by anything except for the ripple of a pond, the warble of a bird, the rustle of wind snaking through trees. Maybe the ice clinking in your glass.

A reverent hush used to prevail in movie theaters no matter what was playing but now the volume of soundtrack-booming movies and moviehouse attendees can deafen you. Sometimes that’s a good thing. Nothing is more glorious than the denizens of Downtown Brooklyn dancing along to Step Up, and what would a crash-and-burner like Fast and Furious 6 be without the satisfying crunch of metal? But mostly the noisiness of a movie-going experience makes me feel like I’m in the middle of Times Square. Today.

L’avventura doesn’t, though. About a woman and man who fall in love while searching for his missing girlfriend, the movie is blessedly quiet, as if it doesn’t wish to miss any detail of its own sensuality. And nor should it. Antonioni’s characters are always animalistic—nearly mute in their raw expressions of envy, sorrow, fury, desire—and thereby even more purely human. With L’avventura as with all of his films, plot is to some degree besides the point and time moves glacially, if at all. What matters is staying as present as a cat, as a child, as a lover, as a beginning and as an ending. And that entails listening as well as looking.

There in Film Forum yesterday I succumbed happily and wholly to the roar of the ocean, to the shadows cast by lovers kissing against a sea wall, to the whisper of bedsheets against a woman’s skin, to the ecstasy of her legs, nude, as they kicked in the air, and to the click of her shoes upon the cobblestones of a city street. It all looked and sounded wonderfully cool and even more wonderfully lonely. Much like nature herself.

L’avventura can be seen in a lush 35mm restoration at Film Forum July 12-25. Go see it.

20 Feet From Stardom Is the Absolute Best

20 Feet From Stardom, Morgan Neville’s documentary about backup singers, deserves an objective review because without any qualifications it is the finest film of 2013 thus far. It channels its subjects’ greatest strengths—big wind, an uncanny ear, a fastidious work ethic, a knack for knowing when to sing and when to stop, and an indomitable spirit—and in doing so pulls back the curtain on a rarely considered world, which is the very best function a documentary can fulfill. What’s more, by suggesting with an infectious, clear-eyed joy how this world connects to everything else, it fulfills one of the very best functions of any movie.

But part of what makes this film so extraordinary is that it summons really personal responses. I’ve seen it twice so far and during both screenings the audiences—full of professional critics!—spontaneously burst into applause and tears more than once. God knows I cried through both showings.

At this point I’ll come clean with my own association with the material. My father, an atheist-Jewish computer science professor hailing from lily-white Massachusetts, has had a lifelong romance with R&B, soul, doo-wop, gospel, blues. Certainly he’s not the only Jewish man in his generation to evince a passion for what’s still sometimes known as black music (I won’t even get into how complicated that is) but his commitment has proven steadfast and often endearing. In our family a Sam Cooke or Aretha Franklin album was always spinning on the turntable or pouring out of the car speakers. And at every opportunity he sang those songs himself, warbling in his cracked, earnest falsetto while I did backup.

He taught me young. Starting around 5 or 6, I learned to listen closely so that whenever he’d break into a lead I could chime in with the right oohs, ahhs, babies. I’d croon “No, no, no” while he’d howl Frankie Lymon’s “I’m Not a Juvenile Delinquent.” He’d sing “Respect” and I’d add, “Just a little bit,” just like Aretha’s sisters did. Did I want to sing lead? Not really. I was a daddy’s girl who was fiercely proud to support him as he sang his heart out. But as I began to come into a limelight of my own—around age 11 I started doing some TV spots—my father and I began to part ways. I couldn’t help but observe he preferred to sing lead in his own house, and from this I learned the classic lessons of the backup singer: that sometimes it was better to blend than to shine, that adaptation was necessary for survival, that you had to know when to cut your losses, and that I loved the music for its own sake, regardless of whether I could gain any rewards by doing so.

So I get backup singers. And the dynamite news is that Morgan Neville does, too. He doesn’t trip over himself as he carefully builds the arcs of these individual women’s lives into something that is, fittingly, bigger than the sum of its parts. Starting with a credit sequence in which he slyly reappropriates artist John Baldessari’s work by applying dots to the lead singers in vintage R&B images, Neville draws upon whatever works best to tell this ultimate underdog story. He enlists some of the biggest names in the music business—Sting (poncey as ever), Bruce Springsteen, Stevie Wonder, Mick Freaking Jagger—to lay out the enormity of these women’s contributions to the twin canons of rock and roll and R&B. Wisely, though, he mostly lets the women speak for themselves. Continue Reading →