Didion’s Not-So-Magical Thinking

I’m trying to sort out what I think about Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking.

I’m trying to sort out what I think about Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking.

I’ve always admired rather than adored or identified with Didion. It seemed to me her best work was created when she was younger, when she still felt fragile and vulnerable and used her writing to steel herself against the cultural and personal abyss roaring beneath her Pappagallo flats. It was in that vein that “Goodbye to All That” was anthemic. Today this essay about leaving NYC still speaks poignantly of a particularly fraught, personal-is-political moment of the mid-twentieth century, as does the rest of the rightfully lauded Slouching Towards Bethlehem. But by the ’70s, when she was firmly established critically, commercially, and domestically, her writing, always economical, grew sparse and sometimes remote.

She’d always alluded to great feelings, even great passions, but in a way that never threatened to disrupt her prose. No menstrual blood stained her diction; no hysteria drew undue attention to individual paragraphs. She rejected the navel-gazing of her generation as paralyzed introspection, and purported to embrace action, movement, John Wayne sere. But that lack of a psychoanalytical impulse only translated into an ever-cooler inertness, sometimes even a flat line. Politically informed but mostly unaligned, spiritually and ideologically fluent but unconvinced, it was as if she didn’t need her reader to like her so much as admire her. As a rule of thumb I admire any woman who doesn’t sing for her supper. In the case of Didion, I did so with a reserve that matched her own.

More and more, I suspect anatomy truly is destiny. Despite my political and academic training, I’ve come to believe our physical bodies are blueprints for the kind of experiences we create or crave or fear. Even as online everything makes it increasingly possible to transcend our bodies, we also are increasingly rooted in and defined and haunted by them. Or is it more that both are of a piece, that our written voices are in fact just another projection of our corporeal beings, however phantom? It is a long, controversial conversation that’s best pursed elsewhere, but I touch on it because any discussion about Didion always reveals these biases.

Suffice it to say I am a tall, blowsy woman with a big voice and a big mouth — there is a reason I call myself a broad rather than a chick — and I write long sentences and pieces that either send you packing or seduce you despite yourself. And as a blowsy broad, I’ve never resonated with Didion’s compact limbs and compact prose though I’ve closely studied the mechanics that facilitate those famously unruffled surfaces. I’ve even copied out some of her passages to experience what it’s like to write with such powerful restraint. Yes, a rawness lurks in between those carefully arranged lines, but there is something censorious, even stunted, in her economy that displeases me. Her screenplays–hackneyed in a uniquely “let’em’-eat-twinkies” sort of way–also allude to a mercenary quality.

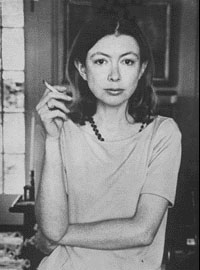

I had intended to go on here and write that Didion’s prose always mirrored her ungenerous, angular physicality but I looked at some of her older bookjackets and a sly-eyed, full-lipped subvert looked back. Yes, she was slim and small, but it would be wrongheaded to assert that she always had been the tiny, hawkish woman she is today. Recent experiences, and perhaps that infamous restraint, have wizened her. Like the irritating comment every woman hears when she hits 30: “From now on, it’s your ass or your face.”

Which leads me to all the brouhaha that has greeted Didion’s recent publication. I still don’t know many who’ve finished the new book, but name a major publication or lofty public radio affiliate and you’ll find pages and hours of genuflection at the altar of St. Joan. It is a best-seller at most bookstores here in New York. Her readings have been standing-room only.

Are people so agog about this new memoir because they feel protective of this fiercely slight woman? Or are they drawn to her brand of “cool customer,” as she describes herself with a characteristic irony? As arguably our nation’s ideal lady writer, hers is a calm, collected femininity: no flab and no fuss. Literally and literarily, we can count on her not to throw herself on her husband’s grave.

She was the right kind of girl, then the right kind of woman. Now we are looking to her to be the right kind of widow. She’s poised to fit that bill, with just the right dose of self-awareness.

For central to the intrigue that cloaks Didion like a mink is her marriage to writer John Gregory Dunne. While the rest of the country divorced and remarried and divorced again, Dunne and Didion worked and lived together, presiding over the American literary scene as a golden couple who straddled the NYC hustle and Hollywood shuffle seemingly effortlessly. They wrote reviews and nonfiction and fiction and screenplays sometimes together, sometimes separately, and mostly, it was reported, in the same room. But if Dunne’s bluster allowed for–dare I say enabled?– Didion’s remove, I wondered if the safety of that union also hampered her prose. Their codependence seemed key to her status as “the right kind of woman”–as in, not so strident that she couldn’t keep a man. Certainly she leaned on Dunne, as she writes in this memoir, “to stand in between [her] and the rest of the world.”

I must admit — I’m not proud of this — that when the news of Dunne’s death hit the wires I was curious about how his widow would bear the loss. That I might not have been the only one also explains how eagerly her book was anticipated. (Perhaps the breathless reviews are compensation gestures for that prurience?) I wondered: Would her characteristically bloodless prose gain some color? Would the floodgates open, shedding insight not only into her union but her famous containment? Would she genuinely (finally) evolve creatively and personally?

The answer, honestly, is no.

In this slim tome and in the many interviews she’s conducted since its release, she acknowledges she writes because that is how she makes sense of her life. She has also acknowledged that she has looked forward to the flurry of distractions that the book publication has promised to provide her. All of which goes a long way toward explaining this slender volume’s stunned, stunted prose but not toward excusing it. I find this memoir genuinely alienating, even self-aggrandizing. In fact I resent it, just like I resent everyone’s piety in their treatment of it.

Didion is still the careful researcher, wading through written material about the process of grieving for–what? Insight into how she should behave? Into what she is feeling? Fodder to fill out her anorectic paragraphs? She studies psychological texts, consults poets. And she lingers longest on Emily Post’s etiquette manual on mourning, ostensibly because Post accepts death as a part of life. Really because Post regards grieving externally, providing practical instruction in the proper appearance of mourning. Didion is still very concerned with the surface of things, if only to approach her situation cautiously from the outside in. Still with that signature remove.

Perhaps as a result of writing those screenplays, Didion’s prose has grown increasingly cinematic, with observations neatly folded into anorectic paragraphs and a strange redundancy of phrases that do not substitute for the punch her earlier prose packed. The Year of Magical Thinking is no exception. No doubt because she wrote it in the first year after her husband’s death–a year crowned by the loss of her daughter, who surrendered to an illness about which Didion is also doggedly avoidant–she writes like a child tasting her own tears with numb wonderment. Even the repetition of that most shattering of sentences–“my husband is dead”– devolves into cliche rather than keening rhythm because it is married to no insight, delves no depths. I get the same feeling here as when I view Woody Allen’s movies: that this is art made to dissociate from the rigors of reality rather than as a bold effort to accept them.

Understand I do not condemn Didion for being shellshocked about losing her husband and child in the span of one year. I do, however, resent the brittle book she wrote about those events to avoid genuinely experiencing them. I resent that she did not have the courage to surrender to her grief before she took up a pen to write herself back into shape; I resent that she failed to use those losses as a way to connect to a larger context that for a very long time she has merely judged. As a reader, I feel..used. Transitional object in absentia.

For let me say it out loud. Her loss, though great, it is not the worst thing that has ever happened to anyone, especially not in recent history. And even if it were, the sheer accounting of it would not merit publication. Many, many women have lost their families and not written books about it. Why Didion’s book could have been special is because she could have shed insight, with her characteristic finality, not into how she healed, for healing from great grief is not a finite process. But insight into how she got through the initial shock of it. Instead, she seems to have written this account of her husband’s death in an effort to not to get through it. Aptly titled, it reads as a (seemingly unsuccessful) meta-attempt to coax herself into believing it took place at all, the way an overtherapized person will tell you over and over that her parents abused her so she will believe it is true. I long for what Didion eventually might have authored had she not written this last year away in a dissociative, now overly lauded fugue. Or is that more magical thinking?

I don’t know Didion’s official stance on blogs, but I’m going to take a wild guess that she views them with disdain. And yet, what she’s written here evinces blogs’ worst qualities with none of their intimacy: Information introduced and reintroduced endlessly without ever fully being digested. To wit: Your husband is dead. By the way, your husband is dead. Your husband had heart trouble and you didn’t want to face up to that. Now he is dead and you don’t want to face up to that, either. Your daughter is dangerously ill for reasons you don’t want to unpack. Now she is dead, which you also won’t unpack. By the way, everyone is dead. By the way, the end.

How about: How will you go on? How have you gone on so far? What does your abyss look like, and what have you excavated from it? How will you find emotional and physical sustenance, and from whom? In recent interviews, you have confessed you didn’t like being single before you married Dunne. Do you know who you are separate from his embrace? Have you the courage to find out rather than subject us to ever-more brittle prose? Will you examine your meticulously unexamined life?

Her answer, at least according to this volume: not yet. My suggestion to the rest of us: Wait until she is. It still could be magic.

This Month’s Reverent Hush (Touch the Sound; Capote; Good Night, and Good Luck; Forty Shades of Blue)

Like most underfunded documentaries, Touch the Sound hasn’t achieved much of a theatrical run and isn’t that easy on the eyes; it’s got the feel of a PBS piece you might watch idly on a slow night. But its narrative about Evelyn Glennie, the profoundly deaf musician who trained herself to hear by mobilizing other senses, shines unexpectedly when it recreates her aural experience. For long stretches, noiseless, wordless urban and pastoral landscapes are punctuated only by the occasional whistle or honk or clang. Upon that foundation of silence director Thomas Riedelsheimer builds what is essentially Glennie’s ideology about sound — namely, that we can hear with our entire beings if we tune out the static of modern life. A curious sense of liberation lingers after the film ends. It is surprisingly seductive, that stillness.

It is a quiet to which moviegoers clamor more than we realize.

The recent buzz generated by Capote speaks to that desire. Directed by Bennett Miller and featuring a tepid script by Dan Futterman (Robin William’s spineless son in The Birdcage), this filmic essay about how the late author constructed In Cold Blood (and himself in the process) isn’t really anything to write home about. It neither delves fully into the timely, fecund topic of journalistic ethics nor does it impart new insights into that puckfaced conundrum himself. Mostly, it’s a terrific vehicle for Philip Seymour Hoffman as Truman, although impressions of famous people are dubious achievements that are grossly overestimated by Hollywood. (The Ray Charles-inspired Jamie Foxx vocal on Kanye’s so-good “Gold Digger” packs much more bang for your buck than the whole of Ray.) In fairness, Hoffman not only delivers what by all accounts is a spot-on simulation of Capote, but he gives the kind of subtle, discomfiting performance that has become his trademark, as does Catherine Keener as author Harper “Nelle” Lee.

But Hoffman and Keener aren’t really why the film has flipped so many wigs. Half a dozen features have been released this year that contain equally compelling performances. It is Capote’s voluptuous quiet that appeals to the many critics and audiences worn down by bombastic Hollywood soundtracks and the incessant, self-conscious chatter of indies. The first few shots of Capote say it all: a wintry, Midwestern terrain, austere and beautifully blank. A family home, neutrally colored, perched primly at the edge of the prairie. A girl who enters that house and discovers the bloodied corpses of her friend and her family — at which point the camera scurries to the cacophony of a Manhattan evening, presided over grandly by the see-and-be-seen king, Mr. Capote himself.

It’s a transition that sets the tenor of the entire feature: the famous socialite-writer as a kind of whistler in the dark, a rabblerouser who rouses good neighbors in the middle of the night from much-earned sleep; the disquieter, essentially. The success of this film does not lie in our fascination with this ‘50s/60s icon and his self-pitying amorality. It lies squarely in the tranquility disrupted not only by abject criminals but by the brigade of their documenters that was led by Capote. For the real journey of this film is Truman’s eventual, painful surrender to the silent roar of middle America, and to all the terror that it can contain. It is in conveying that wretched quiet that Miller and Futterman succeed, perhaps despite themselves.

European filmmakers have always proved quite handy with quiescence; the confidence and depth it requires distinguishes such masters as Bergman, Fellini amd Tati. Not surprisingly, Americans emulators have produced more varied results, as if we’re such a young nation that we’ve yet to stop fidgeting. Woody Allen trips all over himself when he tries on Bergman- (or even Fellini-) inspired somber, and in Gus Van Sant’s trilogy of Gerry, Elephant, and Last Days, “still” slides into “soporific.” But Jim Jarmusch has mastered the evocative silence. It’s what made his career, sometimes undeservedly.(Broken Flowers is a recent example of undeserved accolades.) And part of why George Clooney hasn’t been hung out to dry for his overtly political allegory Good Night, and Good Luck, which hones in on how Edward R. Murrow helped take down the senator from Wisconsin and the Committee of Un-American Activities, is because it’s an economic film. It sidesteps preachiness by telling its story as much through spare sets, black-and-white cinematography and oddly articulate silences as through its snapdragon dialogue.

And then there’s Forty Shades of Blue, which seems less like a European film than a Russian one, albeit one set in Memphis. It also may be the best film released this year in the US. At the least, and that this is a necessary qualification shocks me, it is the best US nondoc of the year. (Murderball and Grizzly Man are outrageously good.) About a triangle of sex and resentment (love factors very little into this geometry) between an aging, debauched R&B; producer Alan James (Rip Torn), his significantly younger, Russian immigrant girlfriend and baby’s momma Laura (Dina Korzun), and Michael, his resentful grown son (Darren Burrows), it’s blessedly hushed given that it takes place in arguably the heart of American music. Sad and slow, the film’s central tension lies not its sexual infidelities and indiscretions but in the question of whether we have the right to expect joy in our daily lives.

In early scenes, Laura’s true character emerges only through the cracks of her trophy wife veneer: long and lean and pale and clad with more money than taste. She roves about makeup counters, impassively receives her husband’s gestures of affections, applies her makeup with more care than she greets her child. Alan is honored for his musical achievements, and at the ceremony delivers such a heartfelt speech about how soul breached the gap between white and black folk that there’s not a dry eye on the house. Except for Laura, whose expression remains inscrutable as she sips a glass of white wine. Just as she may be dismissed for being an ice princess (and the movie for offering up such a fatuous cliché), the event breaks up, he abandons her for a blowsy blond, and the camera holds on Laura, who, features immobile, shoulders high and tight, strides to the bar where she drowns herself in vino desperatas. Michael is introduced to his defacto stepmother through a half-ajar door as he espies her drunken struggle with a stranger who drives her home but fails to extract the blowjob he no doubt expects.

As the film unpacks, Laura’s exact dilemma grows clear. She lives with greater ease and luxury than she even dreamed of in her former life, but remains dangerously malnourished emotionally, and this is a fact she cannot acknowledge, let alone indulge. To expect more is foolish, even ungrateful in her eyes. When Michael complains about his father’s negligence, she bursts out, “Americans are so spoiled!” When asked how she is, she answers “fine” as if she were willing it so each time. Only the ragged, narcissistic desire of father and son James disrupts the precarious balance she’s achieved between her needs, her highly developed morality and the selfishness of this family of aging boys. She is profoundly sad, in other words, and the film does not shy from laying out that misery.

Scenes heat up leisurely and linger on the bare trees and impersonal, garishly appointed rooms of her surroundings while almost as a sideplot characters make sloppy, fierce love and look disappointedly, longingly, wordlessly at each other. (In this way, the film recalls the woefully undersung Junebug, released early this summer.) The resulting effect is of floating above all that wild emotionality, in the manner that Laura wishes she could. The effect, actually, is deeply Russian: a philosophical investigation of a matter of the heart.

When that deceit inevitably causes her to implode, she jumps out from the car Alan’s driving, striding noiselessly along a deserted American street into a dark nowhere. If this were my perfect movie, I thought, it’d end here.

And it did.

We Americans pretty much never shut up anymore. People blither on their cell phones and thumb their sideberries everywhere and always (even during film screenings); blast out ears with programmatic music and blather when walking or running or showering or shitting. There are virtually no moments left when we have to sit still and grapple with the pain that lurks in every modern template. Only a rarified strain of movies compel us to listen by resuscitating the stillness our daily lives so sorely lack. We are lucky that so many have been released this fall. For at their best, they burrow into that quiet and all it holds, allowing us to channel ourselves and our truest selves through them. And even if we don’t know why we love these films, sometimes we still yield to their deeper lessons and pleasures.

At Your Service

Hi, I’m still alive, and I thank those who’ve continued to check in occasionally to ensure that was so. I’ve been as gappy as my teeth lately; there’s been much to observe, and I’ve needed the off-media time to adequately digest it all. Luckily, in these few weeks, some eminently worthy films (History of Violence being the most groundbreaking) have been released, especially for this time of year, and TV isn’t shirking its strangely multifacted duty. Arrested Development third season, anyone? More HBO Hollywood navel-gazing? Chris Rock’s personal time capsule?

I’ll step up again, finally, tomorrow. In the meanhow: hi. Thank you for stopping by.