The Ecstasy of Influence and Figs

September Saturday morning: Dressing like a camel lady (flannel plaid shirt; long print skirt; beat-up Birkenstocks, albeit silver ones). Digging on Prince channelling Bonnie Raitt through my kitchen speakers. Carmelizing figs with honey and sliced almonds and sea salt and thyme. Spooning it all in with a splash of sheep’s milk yogurt on the fire escape. Trusty grouch-kitty sitting pretty by my side. My early-morning life, thus framed.

September Saturday morning: Dressing like a camel lady (flannel plaid shirt; long print skirt; beat-up Birkenstocks, albeit silver ones). Digging on Prince channelling Bonnie Raitt through my kitchen speakers. Carmelizing figs with honey and sliced almonds and sea salt and thyme. Spooning it all in with a splash of sheep’s milk yogurt on the fire escape. Trusty grouch-kitty sitting pretty by my side. My early-morning life, thus framed.

Communing With ‘Tracks’

To call Robyn Davidson’s 1980 best-selling memoir Tracks a travelogue is a bit facile. It’s not that it doesn’t conform to the definition of a travelogue: It is about her 1977 trek across 1,700 miles of west Australian desert with four camels and her sweetheart of a dog. But for many men and even more women, the book is also an anthem of liberation – from racism, nationalism, sexism, and from social conditioning itself.

To call Robyn Davidson’s 1980 best-selling memoir Tracks a travelogue is a bit facile. It’s not that it doesn’t conform to the definition of a travelogue: It is about her 1977 trek across 1,700 miles of west Australian desert with four camels and her sweetheart of a dog. But for many men and even more women, the book is also an anthem of liberation – from racism, nationalism, sexism, and from social conditioning itself.

Davidson writes:

The self in a desert did not seem to be an entity living somewhere inside the skull, but a reaction between mind and stimulus. The self in a desert becomes more and more like the desert. It has to, to survive. It becomes limitless, with its roots more in the subconscious than the conscious.

To those tired of the “Me Decade” (which has since lengthened into the “Me Decades”; is it possible we’re having a “Me Millennium?”), Davidson’s rejection of the Western concept of the self comprised the very essence of liberation. The irony was that, having achieved an egoless state out there in the outback (however fleetingly), Davidson bristled at the egotism implicit in self-documentation. Practical Aussie that she was, she still dutifully wrote up her trip for National Geographic magazine, her sponsor. She even allowed photographer Rick Smolan to capture her image as “the camel lady,” as she became known internationally. The book she subsequently wrote relayed her journey as well as the ambivalence she felt about needing anything – from other people to words themselves. It’s an unlikely subject for a bestseller, really. Unless you factor in Davidson’s glamour.

An Interview With David Thomson

This interview was originally published in Word and Film.

This interview was originally published in Word and Film.

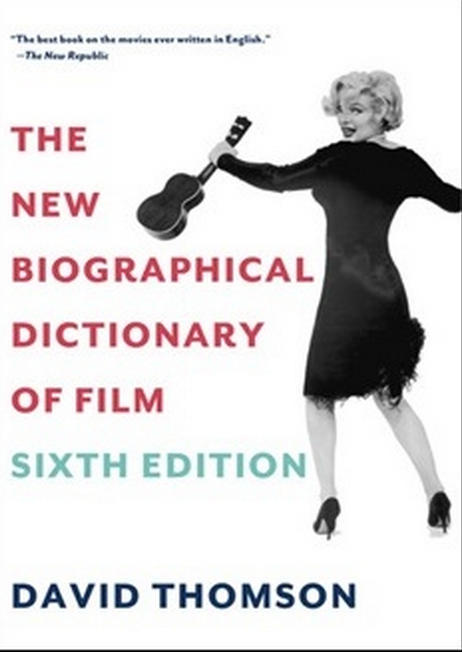

This year marked the release of the sixth edition of David Thomson’s New Biographical Dictionary of Film, published for the first time in 1975. Now at 1,154 pages long, the book isn’t just a reference manual. It’s an exotically rare bird, with more than 1,400 bios that are highly, deliciously subjective – a series of mini-reviews, remembrances, and essays that are as gratifying in their form as in their function. It’s no wonder that the book has a cult following that has expanded with each edition; a 2010 Sight and Sound critics’ poll ranked it the number one film book ever written. A British-born critic who now lives in San Francisco and writes primarily for the New Republic, Thomson fielded my questions with his typical droll candor.

Lisa Rosman: What is the ideal way to read your book? How would you prefer people approach it?

David Thomson: Many people speak of it as a bathroom book – and these days some people spend longer and longer in that room (happily or unhappily). Others speak of its therapeutic bedside role – and the bed can be as vexed as the bathroom. I believe people should dip and then move on to cross-referred topics and let the hours roll by. But the book is heavy now and I like the notion of readers having several copies, distributed through their homes and their lives. [British novelist] Geoff Dyer has admitted that he and his wife read it to each other in bed at night. I suspect they’re worthy of better things. Continue Reading →