Boys in the Ladies’ Room (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, An Unmarried Woman)

So as I’ve been lying about in a radioactive glow from an especially nasty flu, I’ve been inspired me to go back and look at Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974) and Paul Mazursky’s An Unmarried Woman (1978). It’d just occurred to me that Leigh’s feminist-second-wave Vera Drake has an interesting precedent in these two films. Plus An Unmarried Woman keeps showing up on the WE Channel, which is my most shameful secret viewing vice besides Oxygen and, well, Lifetime. I am a woman who loves Women’s Entertainment television programming, apparently. Hear me roar.

Both of these films were made by very accomplished male directors smack dab in the heart of women’s liberation. Remember the ERA? At that, remember when people even wielded the term women’s liberation with nary a smirk? Or was that smirk ever successfully suppressed? (I was but a lass, it must be said, and my mom and her girlfriends were too busy drinking coffee and making fun of their husbands to be duly invested in a revolution.)

At any rate, An Unmarried Woman makes me reasonably happy; Alice does so only remotely. I’d remembered it as hard to watch, and not in that rewarding drink-your-French-cinema

-it’s-good-for-you way. Watching it again, I regret to report that it’s still a bit of a drag. I dig that it’s the story of a Southwestern working-class woman who harbors artistic rather than middle-class aspirations — an awfully rare distinction these days — but Scorsese is off his turf here both topically and geographically. Partly this has the dutiful feel of a studio assignment, which it really was (his first). Partly he doesn’t seem to like women: Beware the wrath of the ugly short man.

Alice (Ellen Burstyn) is a mom who’s been newly widowed by a man whom she feared more than loved. She finds a new job in a new town as a singer, but loses it when a new lover turns out to be a married psycho (Harvey Keitel, using his beady eyes to good effect here). Then she works as a waitress in a podunk Arizona town, comes crankily to the revelation that she’s never learned how to live self-reliantly as a woman, and so naturally enters a relationship with a rancher who’s not nice to her kid. To be fair, the kid is that staple of the divorced-parent movie: a smart-mouthed, precocious toad. Worse, he wears aviator glasses and hangs with a baby dyke Jodie Foster, revving up for a stint as a Taxi Driver’s child prostitute. The film’s not very nice to look at, except for the opening segment, a Wizard of Oz homage flooded with blood-red. It’s strange to watch Scorsese fool idly with techniques such as fast zooms that he’ll use to such better effect later. Mostly the film is filtered through the grainy, sun-dappled lens and cinema verite shtick that was the downside of 70s cinema.

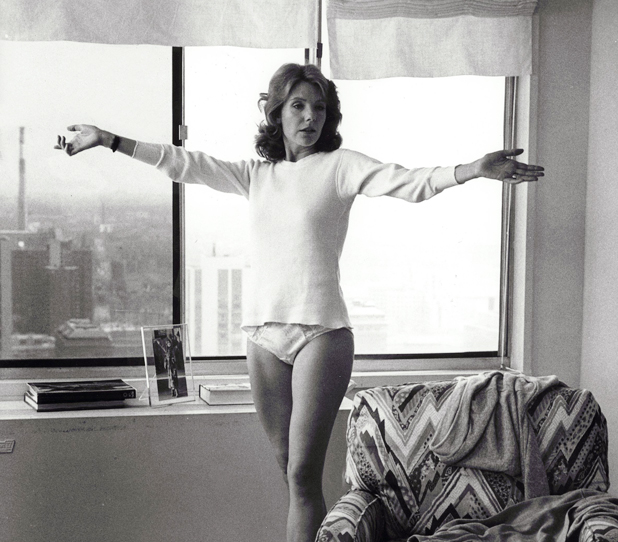

An Unmarried Woman amuses me more, basically. It’s set on the Upper East Side and in a very nascent Soho. It’s always fun to look at New York in the other eras, and Mazursky excels at pleasantly gossipy, two-hour social tableaus. God love Jill Clayburgh’s cowl-neck sweaters and capes; the small glasses of white wine in the “single bars”; the enormous artists’ lofts littered with the abstract paintings; the jogging in turtlenecks; the C-R session drawled out in New York nasal; the “I smoke grass, you know” daughter (another toad variant); the feminist shrink with the severe middle part and a whiff of macramé.

Clayburgh is Erica, a Seven-Sister grad at the very top of her 30s, whose Wall Street husband suddenly ditches her for a girl at a Macy’s counter. She’s still got her middle-class cache — cash, digs, gallery job — but is at a loss about what to do with the rest of her life. Same sentence: “I don’t know who I am without a man.” Like Alice, her solution to that problem is to be with more men. She’s even nabbed a bearded lover, same as Alice — British, porcine Alan Bates rather than Alice’s working-class hero Kris Kristofferson. But how I rationalize preferring Mazursky’s film, when it’s equally as trite but diddles with bourgeois dilemmas rather than the working poor’s tawdrier sprawl, is that girlfriend doesn’t rise to her boyfriend’s ultimatum. At the end of Unmarried, Erica refuses to follow her artist to Vermont. As punishment, he takes leave and saddles her with an enormous painting that she’s forced to heft by herself through city streets. Given his crap art, it’s punishment indeed. Still, there’s something endlessly hopeful about Clayburgh wobbling through early Soho in earth shoes made for walkin’.

More seriously, what these two directors lack, which Vera Drake director Mike Leigh possesses in spades, is a willingness to imagine these characters as truly distinct from their connection to men. Burstyn and Clayburgh do their damnedest to fill in the gaps left by male screenwriters and directors. Burstyn in particular gamely does her generous, wide-lipped best with the plenty-of-nuthin’ that landed in her lap. But Scorsese and Mazursky can’t quite conceive a truly female space for their female protagonists. When abandoned by her husband, Erica is left almost entirely to her own devices; except for one over-earnest, utterly humorless powwow with women we never meet again, no girlfriends rush in to pick up her pieces. Where are those seven sisters when she needs them? And the liveliest scenes in Alice are when Alice and Flo (Diane Ladd) crack each other up while they are sitting in the sun or holed up in the ladies’, but those scenes are few and far between. Relegated to the ladies’ indeed. It speaks volumes that when Alice was reinvented as a sitcom, it focused almost entirely on the relationship between Alice, Flo, and a third waitress, hapless Vera. TV’s less skittish when it comes to las hermanas doin’ it for themselves.

I’m still sorting out why TV does better by women than film often does. For one, it inhabits the same domestic ghetto to which the feminine is still mostly banished — both are literally stuck in the home, where stakes are, if not lower, certainly perceived as less urgent. Typically great directors still don’t bother themselves too much with TV, though cable is certainly changing that. In fact, many of the interesting women directors of the last decade have been resurrecting their careers on shows like The L Word (Rose Troche), Six Feet Under (Lisa Chodolenko), and Sex and the City (Alison Anders).

But many of the best American male film directors continue today to try their hand with the woman in self-recovery. Some, like John Sayles with his Passionfish, succeed more with such material. Most succeed only mildly, if at all. (I regret to remind you of Spike Lee’s Girl 6.) In sooth, short of earning their cub scout “sensitive” badges, I wonder what compels these men to tackle what used to be called women’s films and now are called — I wince as I type the words — chick flicks. Only they’re not called chick flicks when the really big boys direct them. Mike Nichols’ movies, for example, are typically the ultimate chick flicks (see the brittle dirge Wit or, for a real paean to Yuppie careerism, Working Girl) except that no one would deign to call them that, especially at awards ceremonies. Which is fine, anyway, as his women don’t really seem to like other women. Huge mistake. Never trust a woman without women friends, and never trust a movie about a woman’s pilgrimage that doesn’t include her women friends.

Of these big boy directors only Mike Leigh has recently painted a plausible women’s world. Funny that it’s still all about women’s plumbing. One of these days on the silver screen, women in packs will more regularly tread further than the ladies’ room. Excuse me, excuse me. Women’s room.

Don’t Shit Where You Eat (Untitled, Undeveloped Short Film)

I offer a moment that should live inside somebody’s screenplay. Not mine, because I entertain no desire to write one. But really, this belongs in some Euro or indie something-or-other.

I offer a moment that should live inside somebody’s screenplay. Not mine, because I entertain no desire to write one. But really, this belongs in some Euro or indie something-or-other.

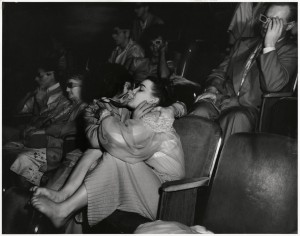

This morning: rainy, cold, drear. Sitting in the coffee shop window, I was feeling smug that I didn’t have to hustle to work like all the Rick Springfield mofos hastening by. One of the coffee jerks — twentysomething, hugely pregnant, more blowsy than blooming — waddled outside, followed by a small young man with bright, dark eyes. They stood, kissing gingerly for a surprisingly long time as everyone streamed around them. I couldn’t stop gawking. So little apparent passion, and yet the kiss dragged on forever, tongues flashing and everything. Eventually, they disentangled and I went back to my crossword. An hour later, on the subway platform not a half-block from the coffee shop, I saw the small man again. With a far greater urgency, he was kissing someone else — a slight, pretty blond girl. The kind of girl who’d be your basic nightmare if you had eight months of baby sacked in your gut.

Sox and the Shitty: Why Desperate Housewives and The L Word Can’t Fill Sex and the City’s Shoes

Sunday night TV has got me wishing I were a dyke again.

People used to mock me for loving Sex and the City, but I had a very good reason: It rocked. Yes, it was a hyperbolic version of the lives of single Manhattan women, but anything worthy on TV is hyperbolic to the extent that hyperbole is required to make broad strokes visible on small screens. During the show’s entire run, it was still against my politics to pay for television, but it didn’t matter. I wasn’t too principled to leach other people’s paid-for television, and almost every girlfriend I had sacked out in front of HBO Sundays at 9 pm.

The girls of SATC (an acronym my boyfriend had to master before I felt comfortable calling him my boyfriend) were single, well turned-out, feminine, old school-new school, and really fierce about their friendships with each other. When they obsessed about boys too much, they called each other on it. They laughed from their diaphragms, not through their noses. They were different from each other, and respected those differences. They wore serious stilettos. They knew how to argue without reverting to passive-aggressive bullshit. They talked about sex in bawdy detail. They were adamantly on each other’s sides, but never to the degree that they shined each other on. They served as moral barometers for each other, though rarely as moral watchdogs. The omnipresent puns grated sometimes and the Manhattan they inhabited summoned a fairytale most of us hadn’t visited since the late ’90s. But Charlotte, Samantha, Carrie, and Miranda (my favorite) delivered the most accurate yet utopian portrayal of female friendship that’s ever graced television.

None of what I’m writing here so far is original, and that’s the point. For the first time, a TV show captured not just un-Cathy-like dating but the friendships women formed in our 30s, and scores of us ate it up with a spoon. With most of our peers dropping like flies into the land of two, those of us still single in our 30s (and yes, 20s and 40s and insert-decade-here) had learned to rely on each other, to ask more of our friendships than that we merely be audiences for each other’s travails. For those of us who were still single, especially for those of us who opted out of panicking about our singlehood, the time we spent with our girlfriends was primary, not secondary, possibly for the first time since many of us had hit puberty.

SATC reflected that. It also reflected a way to be feminine, sexual, witty, and still very, very genuine.

Growing up in Boston in the preppy ‘80s, I learned that as a woman, you had two options in terms of how you presented yourself: neutered or slutty. Naturally, I opted for a psychedelic brand of slutty, but it wasn’t a perfect fit since, as an anorexic, I was infinitely picky about what I put in my mouth. A women’s college solved that problem: At Bryn Mawr, the dykes were the coolest women I’d ever met. Unapologetic, funny as hell, immune to Ophelia’s malady, these were broads to emulate. That I didn’t really dig chowing box (thank you gawker) was irrelevant for a while, though it did peeve my boyfriends — huge rugby players, inevitably — to have to hide when I ran into any of my friends.

And that was the delicate balance I preserved until I moved to NYC, where I learned from both drag queens and Southern fashionistas how to project a different, more capable sort of femininity. That steel magnolia mythology is the real deal: Those girls taught me how to discuss a 401k and a good lipstick in the same conversation. I learned from the drag queens still strutting downtown in the mid-’90s how to say no to the wrong guy, and then stop dwelling on it. I learned how not to apologize for myself. How to flirt. How to more fully occupy myself. And how to be a real girlfriend not only to my boyfriends, but to my girlfriends — as that’s only possible when you’re no longer just looking for confirmation or a mirror image in your mates. It’s called your 30s, if you hang in there long enough to achieve that self-reckoning.

Enter SATC. Candy that we could digest.

I liked that Miranda bossed her boyfriend Steve around too much, and that her personal evolution entailed compromise rather than capitulation. I liked that in her struggles with Big and her other boyfriends, Carrie managed to flounder without entirely losing her sense of humor. I liked that the show changed when the city changed post-9/11, as did Carrie’s wardrobe. I liked that when a baby was introduced, the show didn’t change its entire tenor. I liked that the show was actually shot in NYC, and looked like it, but better. I liked the Barbie-on-coke wardrobes, even if they did render moot everything my friends and I wore with an alarming regularity. (I’m done wearing heels with jeans and kitsch t-shirts for at least a decade, thank ya veddy much.)

And no show ever made me cry so much. When Miranda’s mother died, and Carrie jumped into the funeral procession so that her girl wouldn’t have to walk alone, I wept. When Aidan dumped Carrie for cheating and she leaned into her girlfriends at Charlotte’s wedding for support, I wept. When Carrie stood alone at her book party and said, “My loneliness is palpable,” I wept in recognition. When Samantha got breast cancer and told her oncologist to fuck off for suggesting her single lifestyle was to blame, I wept, too. When Miranda proposed to Steve and married him in a community garden, I wept like a baby.

Here was a heterosexual model of enterprise and friendship and maturation that I could recognize and even aspire to. It was my friends and I reflected in good television: a place we could climb into just when Sunday’s mean reds came calling, which is arguably the main point of TV in general.

The show ended just when almost the last of my straight girlfriends my age leapt into family, hetero style. 2004’s been a lonely year in many ways. I’ve finally found myself found a man equipped with the ability to wink at me across a room, buy flowers when I’m sad, and let me be nice to him without freaking out. But still: It’s quieter these days. I miss the chatter of my girlfriends, disappeared into admittedly worthy occupations like motherhood and the cities and suburbs where they grew up or where they or their husbands found jobs. I never thought it would happen, but, lordy, it did. With the first bloom of youth decidedly lifted, I’ve started to feel less like a pioneer and more like an alien as an unmarried woman. I get cross when everyone acts like my life has wildly improved just because I found a good man. He’s wonderful, but those days when we straight women weren’t so divided out into mommy-daddy pairs were wonderful, too.

It seems too much that, at the same time, in SATC’s timespot CBS has cynically offered us the debacle Desperate Housewives. The show’s about women roughly my age who’ve morphed into abstractions of the worst every decade since WWII has had to offer in the way of housewifery. It’s only accurate in the worst possible ways: the Stepfortification, the Mommy’s little helpers that have afflicted some of my coolest female friends. The Desperate equation for success is apparently bad writing + a cast comprised of the dregs of expired nighttime soaps (save Felicity Huffman, who’s always better than the shows she appears on) + cleavage + desperately bored women (and men) at 9pm = high ratings. Though Desperate could’ve offered a smart look at how the role of wife and mommy still gets ghettoized despite our best intentions, it’s really just Twin Peaks minus the irony and plus an estrogen infusion. Or Lucy and Ethel on Zoloft and Ritalin, a deadly dull combination.

This is not what I signed up for when I emigrated to NYC. Not in my Sunday night TV, and not in my real life. Something greater has to loom between acne and menopause than this mishegos.

So I’ve reverted, once again, to a by-proxy lesbianism: The L Word. As the show’s set in LA, some of these dykes are far more lipsticked than I, and though neither they nor the show they appear on are as funny as my Miranda, at least they live in the ballpark of women that I know or even like. I can see hanging out with them, and, indeed, since the first season came out a few weeks ago on DVD, my real girls and I have been shut-ins. We can hardly wait for the second season. It’s just I’m the only one who’s not a dyke. Again.

At this point, I’ve gravitated back to the gay community for personal inspiration not because I don’t like who I am but because, gay marriage laws notwithstanding, more models exist here of how to sustain connection and character outside of the traditional heterosexual trajectory than anywhere else. There’s got to be more options represented for those of us in our mid-30s without babies or husbands — or at least those of us who don’t wish to have babies and be in relationships the way that we were taught.

Bottom line is there’s got to be more models for smart straight broads of a certain age than lipstick lesbians and desperate housewives. And there are. They’re just not yet on the dial.