The following is a review originally published in Word and Film.

The following is a review originally published in Word and Film.

Violette, about French author Violette Leduc’s quest for success, may be the ultimate literary love story: At core, it depicts how the creative process can be seen as a love affair, both with ourselves and with an imagined audience. It takes a lot of fortitude to sit still with the imagination – to trust that, if we hang in there, we may produce something worth sharing with the world. In this sense, Leduc, who throughout her career had the temerity to demand love for her controversial self-expression, was powerfully strong if also powerfully frustrating. Much like this movie.

To be clear, “frustrating” is putting it nicely. Radical self-exposure was Leduc’s strength in her writing but her weakness as a person, a fact that director/co-writer Martin Provost captures in excruciating detail. French actress Emmanuelle Devos channels Leduc’s inability to contain her rawest feelings – her jealousies, her resentments, her neediness – so effectively that the result is an almost unbearable character. Almost. A woman who won’t rest until she is wanted on her own terms may not be an easy story but it is an important one.

In general, biopics are no easy task – stick too closely to the real arc of a person’s life and get bogged down; take too many liberties and defeat the point of a biographical film in the first place. The best bet is to do what Provost does here and in “Séraphine,” his film about the female French painter: focus on one aspect of the person’s life. In this case, he hones in on Leduc’s twenty-year quest for unconditional love and artistic recognition, spanning from the end of World War II, when she worked as a black-market trafficker, to her 1964 publication of the protofeminist novel La Bâtarde, for which she achieved mainstream success. It’s especially clever that he breaks the story out into six chapters, mostly named after her unhappy personal attachments.

Leduc’s real life was very much as it is described in this film. Born in 1907 as the illegitimate daughter of a servant who never loved her, she went through a string of lousy relationships, jobs, and living arrangements until Simone de Beauvoir (played by Sandrine Kiberlain) helped get her writing published. And what writing! At a time when even the licentious French eschewed such material, Violette wrote explicitly of lesbian affairs, abortions, incest, even the failure of the maternal bond. She fought hard to tell stories that were not being told, and labored in relative obscurity even after her literary circle widened to include the likes of Albert Camus and Jean Genet (played by Jacques Bonnaffé).

Leduc’s greatest enemy in this fight may have been herself. Her hunger for the attention she never received as a child made her “jealous, bitter, and unhappy,” as she says in this film. Even advocates such as de Beauvoir, for whom Leduc burned with an unrequited love, were forced to hold the author at arm’s length. The dynamics between these two – icily restrained de Beauvoir shrinking from recklessly unfettered Leduc – make for terrific drama.

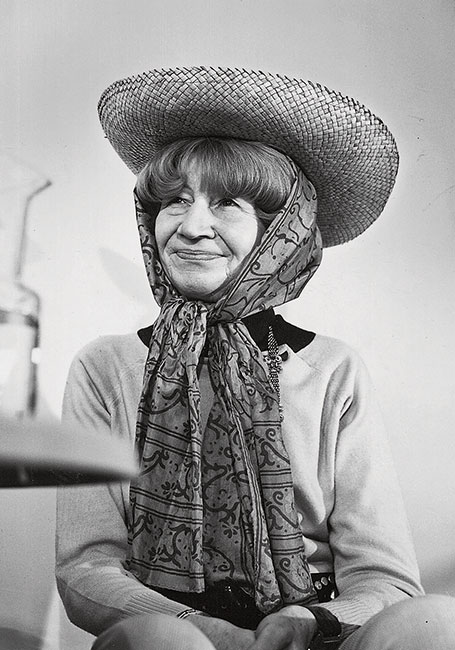

Known best for her work in Kings and Queen and Read My Lips, Emmanuelle Devos excels at portraying compellingly difficult women, and this film hinges upon how completely and unselfconsciously she throws herself into Violette. She spares nothing in rendering the author sympathetic, even heroic – and a wretch. She even dons a prosthetic nose to minimize her elastic beauty. (Leduc baldly referred to herself as “ugly.”) It’s the kind of performance that would score the actress an Oscar – we all know Nicole Kidman might not have nabbed her golden boy for The Hours had she not donned an unflattering fake nose – were it not for the fact that this film is bound to alienate as many as it delights.

Because the laborious process of writing is hopelessly uncinematic, no literary biopic should last longer than ninety minutes and, at 143 minutes, Violette is no exception. We can only watch a woman writhe miserably on her bed so many times, and Leduc’s long succession of romances grows tedious rather than titillating. Yves Cape’s cinematography helps: a natural winter light spills everywhere but upon poor Violette’s features. Madeline Fontaine’s costume design helps: Such complicated hats! Such brilliant yellows and blues! And set designer Thierry François’ strong contrast between Violette’s drab rooms and brightly colored costumes helps most. For if we dress nicely for others’ eyes, we create beautiful spaces for our own, and the film visually plays out this metaphor well. Similarly, the elegant home of Simone, who lived alone during this time, reinforces her supreme self-possession.

Reciprocal love with another person, especially with Simone, may evade Violette but it is no spoiler to reveal she eventually finds a “a room of her own,” a sun-dappled countryside cottage where she writes the books that grant her the mainstream success and creative fulfillment that long eluded her. It’s a testament to this film that we grasp the full import of this achievement. For if we’ve suffered with her on this journey – arguably too much – the relief that floods us when she finally settles down, literally and figuratively, is hard-won. It’s a narrative structure that concretizes what could have been too cerebral a Virginia Woolf-style theme.

literally and figuratively, is hard-won. It’s a narrative structure that concretizes what could have been too cerebral a Virginia Woolf-style theme.

It is fitting that the last chapter of this film is named after a place rather than a person: Faucon, the French rural village that Violette makes her home. In real life that is where Violette died, at age sixty-five. All in all, I’d call that a happy ending.