The following is a review originally published in Word and Film.

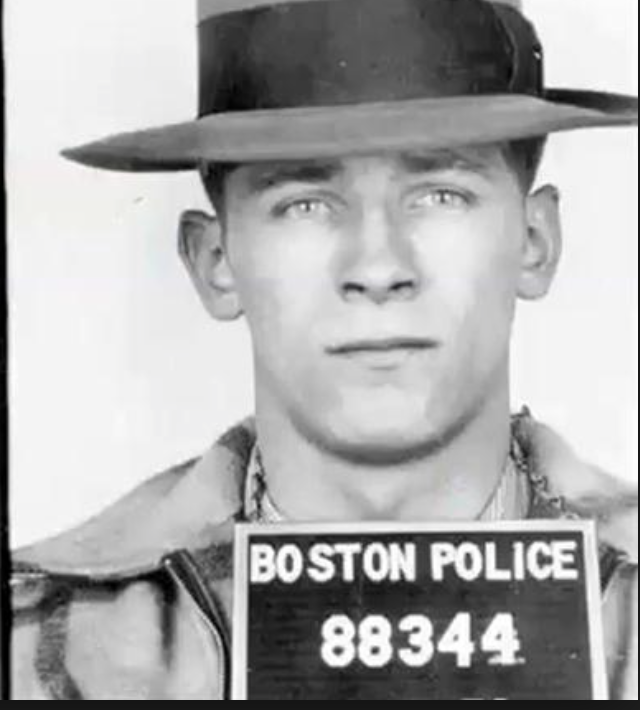

There was a time when James “Whitey” Bulger was merely a Boston legend. Though he ruled a Massachusetts crime syndicate for more than two decades, he really wasn’t nationally recognized until he landed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list in 1994 and a sixteen-year manhunt was launched. (At one point, the award offered for information leading to his capture was second only to the award offered for Osama Bin Laden.) By 2011, when he was arrested in Santa Monica, where he’d practically been living in plain sight, the American imagination was officially hooked. A bona-fide Whitey cottage industry now exists: Martin Scorsese’s The Departed is loosely based upon the blue-eyed mobster; a biopic starring Johnny Depp is in the works; and a bevy of firsthand accounts and journalistic tracts have been published.

There was a time when James “Whitey” Bulger was merely a Boston legend. Though he ruled a Massachusetts crime syndicate for more than two decades, he really wasn’t nationally recognized until he landed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list in 1994 and a sixteen-year manhunt was launched. (At one point, the award offered for information leading to his capture was second only to the award offered for Osama Bin Laden.) By 2011, when he was arrested in Santa Monica, where he’d practically been living in plain sight, the American imagination was officially hooked. A bona-fide Whitey cottage industry now exists: Martin Scorsese’s The Departed is loosely based upon the blue-eyed mobster; a biopic starring Johnny Depp is in the works; and a bevy of firsthand accounts and journalistic tracts have been published.

Part of why Whitey fascinates is his unique brand of sociopathy. With his combed-back pale hair, searing gaze, and apparent pleasure in his work (even in the world of organized crime he is considered vicious), he’s recognized as the most powerful American gangster of the last fifty years – despite the fact that he doesn’t conform to any stereotype of a mob boss. (For one thing, he’s emphatically un-Italian.) But Whitey also fascinates because his reign of terror prevailed, almost wholly unchecked, for so long that it seems apparent he was snug (with a bug) with federal law enforcement agencies. Joe Berlinger’s documentary Whitey: United States of America v. James J. Bulger takes a good, hard look at the corruption that likely surrounded his case.

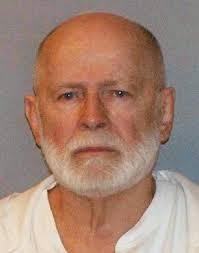

Here’s the deal: By the time Whitey was caught, there was no point in his disputing most of the thirty-two counts of criminal wrongdoing, including complicity in at least nineteen murders, with which he’d been charged. While Whitey was underground, his associates – including bouncer Kevin Weeks, who recounts his own complicity in a chilling deadpan in the film – sold him out to save their own hides. Since Whitey was already in his eighties, he was likely more keen on preserving his legacy than his freedom. Indeed, the legal defense he mounted was more intent on establishing him as a “good crook” – that is, one who did not kill women or serve as a rat – than on establishing his innocence. (Ultimately, Whitey was sentenced to two consecutive life terms plus five years.) Conversely, federal law enforcement agencies, especially the FBI, had a lot invested in proving he was more in their stead than they in his – which is what Whitey breezily claims in taped phone calls. So the real question of this film is: Who was zoomin’ who?

If anyone can penetrate this maze, it’s muckraking director Berlinger, who has proven his mettle with such material in his trio of HBO documentaries about the beleaguered West Memphis Three. Eschewing a voicecover narrative, here he sifts through a T. S. Eliot-level wasteland of conflicting legal perspectives and interviews with journalists, local and federal officials, family members of the victims, and “business associates” of Whitey. But while a clear viewpoint eventually emerges in the West Memphis Three trilogy, the degree and manner in which federal agencies and Whitey are dirty never fully comes to light in this doc.

In their tome Whitey: The Life of America’s Most Notorious Mob Boss, Dick Lehr and Gerard O’Neill chart in rich detail the Irish-American gangster’s lifelong ability to exploit and charm others, including an uncanny capacity for wriggling out of criminal charges that tracks back to his early adolescence. It’s relevant because, regardless of how much information Whitey actually shared with the feds, the fact that he spearheaded an entire crime syndicate means he should have been their primary target  rather than their accomplice. What’s hard to gauge is whether his apparent ability to manipulate the government stems from his personal charisma or its systemic corruption. It’s even harder to gauge without experiencing that charisma firsthand. Alas, Berlinger was granted no in-person access to Bulger, who was already behind bars by the time filming began. Nor was the director granted any access to the trial.

rather than their accomplice. What’s hard to gauge is whether his apparent ability to manipulate the government stems from his personal charisma or its systemic corruption. It’s even harder to gauge without experiencing that charisma firsthand. Alas, Berlinger was granted no in-person access to Bulger, who was already behind bars by the time filming began. Nor was the director granted any access to the trial.

Instead, a portrait of the inherent flaws of current law enforcement investigations emerges. For those interested in crime procedurals, Whitey offers a compelling – and admirably comprehensive – look at the fraught dynamics of various federal agencies, as well as the nuts and bolts of building out high-profile cases. For those who fetishize Masshole culture – and it’s a growing population, no doubt about it – the symphony of Boston accents will prove music to the ears. But for those craving more insight into the malefactor himself, this film will invariably disappoint. Put bluntly, there’s not enough Whitey in Whitey.