Hodge-podge, thy name is The Congress. Ostensibly about an iteration of Robin Wright played by Robin Wright who sells the rights to her on-screen persona to a big Hollywood studio, it is not really about that at all. It is part animation, part live-action; part adaptation of Stanisław Lem’s 1971 sci-fi novel The Futurological Congress, part anti-Hollywood meta-movie; part electric Kool-Aid acid trip, part anti-commercialist treatise. And if all that sounds a bit much, try actually sitting through this two hour-plus film. The funny thing is: I heartily recommend the experience.

Hodge-podge, thy name is The Congress. Ostensibly about an iteration of Robin Wright played by Robin Wright who sells the rights to her on-screen persona to a big Hollywood studio, it is not really about that at all. It is part animation, part live-action; part adaptation of Stanisław Lem’s 1971 sci-fi novel The Futurological Congress, part anti-Hollywood meta-movie; part electric Kool-Aid acid trip, part anti-commercialist treatise. And if all that sounds a bit much, try actually sitting through this two hour-plus film. The funny thing is: I heartily recommend the experience.

It might sweeten the deal to know this is the brainchild of Ari Folman, the writer-director of Waltz with Bashir. A 2008 animated documentary about his experience as an Israeli infantry soldier, Bashir grounded questions about the fluidity of memory and identity with the reality of the 1982 Lebanon War, and deserved the Oscar for which it only received a nomination. The Congress may take Folman’s big-picture interrogations much (much!) further afield but he anchors its fancies with the same sort of real-world stakes. In this case, those stakes are an actual female body, which, as it turns out, cuts through all kinds of blips in the time-space continuum. In this capacity, Robin Wright, who channeled an old-soulfulness even as a budding starlet, proves the perfect muse. But she is also far more than a muse, and it is this dance between her subjectivity and her objectivity – not to mention her objectification – that runs as the common thread through this new cinematic organism that both heralds and laments a new era in filmmaking.

See what just happened there? In even attempting to describe the hallucinogenic dystopia that is The Congress, I fell prey to its confusion. That’s part of this film’s charm, although admittedly it’s not a charm that will seduce everyone. The degree to which it does depends on how deeply viewers are willing to plunge into this Alice in Wonderland-style rabbit hole.

The film’s heady fog begins with a simple enough story of woman against machine. Now in her mid-forties, Robin Wright has been offered what her agent (Harvey Keitel) and studio head (the perennially predatory Danny Huston) swears is the last job offer of her career. Only it’s not exactly a job. Rather, she’s being offered enough money to sit pretty forever in exchange for her computer avatar, with which the fictional studio Marymount can make whatever movies it likes. The hitch? She can never act again. It’d seem like no job offer at all except that Wright’s son is suffering from “Usher Syndrome,” a rare genetic disorder that causes significant hearing and vision loss, and she’s keen to take care of him at any cost. So she literally sells her body, and a scene in which her form and expressions are captured in an enormous disco ball of a contraption is surprisingly, elegiacally lovely.

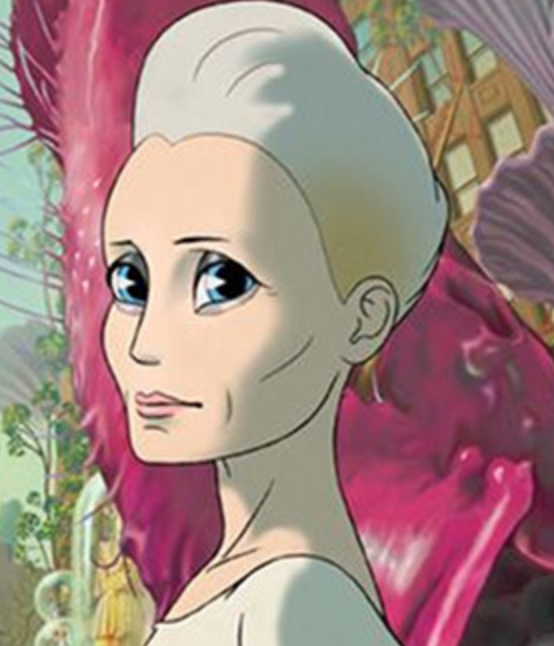

Fast-forward twenty years, and a grayer, more drawn Wright is driving through the desert to a futurological conference held at a massive Marymount hotel empire in a “restricted animated zone.” As she enters, the terrain – and she herself – warps into a cartoon that makes The Yellow Submarine look like The Family Circus. In this not-so-Brave New World, Marymount’s chief action figure is now “Agent Robin,” and the studio is looking to buy the rights to Wright all over again, though this time it wants her chemical essence so viewers can literally consume her. It’s at this point that Folman’s narrative begins to draw from Lem’s super-trippy cult novel, replacing its beleaguered male protagonist with an aged Wright – a Wright who is fuming about the corporatization of storytelling and reality itself. After she delivers a rebel-rousing speech to screaming throngs, she is felled by acute hallucinogenic poisoning, and stirs from a medically induced, decades-long deep freeze to discover that most of the world now inhabits a version of the animated zone, although her son does not. Aided by her suitor, “Agent Robin” computer animator Dylan (Jon Hamm, proving that even his disembodied voice is ridiculously sexy), Robin unearths the horror underlying this mass hallucination now accepted as daily life – not unlike an animated, voluntary Matrix.

What distinguishes this film is also what is bound to alienate many: its ever-shifting conceptual reality. Just as we’ve acclimated to its plaintive, slightly sci-fi first act, The Congress spirals far past mere identity politics into a day-glo, dizzying diatribe about the dissociative lifestyles of the (wannabe) rich and famous – and then it morphs again into an indictment of the collective hallucination that is society itself. The result: We feel as involuntarily high as all of this world’s denizens turn out to be. Forget method acting. This is method viewing, and the disjointedness feels not only intentional but pedantic: Don’t trust the ground beneath our feet, don’t assume our bodies are our own, don’t assume anything is real.  The only common denominator of the myriad puzzle pieces is Wright’s pining. She pines for her sick child; she pines for a world that’s already disappearing at the film’s inception. It’s not for nothing that her son’s affliction robs him of his senses; we’re meant to ask what exists beyond what we can see, hear, even touch.

The only common denominator of the myriad puzzle pieces is Wright’s pining. She pines for her sick child; she pines for a world that’s already disappearing at the film’s inception. It’s not for nothing that her son’s affliction robs him of his senses; we’re meant to ask what exists beyond what we can see, hear, even touch.

Is this film subtle? Yes and no. Its speeches are long and labored; its small talk, nonexistent. Yet so many messages layer upon themselves in an assault of visual imagery that it’s hard to unpack everything in one sitting, and the result is so compelling that some might not mind re-watching it on auto-repeat. (I didn’t.) The Congress is like an addictive drug whose primary effect is a desire for a detox. In these hyper-dissociative times, this may be just what the doctor ordered.

This review originally appeared in Word and Film.