If science fiction shows us what we fear about our future, horror films show us what we demonize now. Take last year’s “Mama” and “The Conjuring.” Though quite good, both channeled our culture’s feminist backlash by indicting women who defy their “natural” maternal instincts. “The Babadook,” the debut feature from Aussie writer-director Jennifer Kent (expanded from her award-winning short “Monster”), may press that same bad-mommy button, but it does so with a great deal more insight and compassion – not to mention a crafty girl aesthetic. Imagine a movie hand-stitched by an Etsy queen or, better yet, a Bust Magazine editor, and we have some sense of what “The Babadook” brings to the table.

If science fiction shows us what we fear about our future, horror films show us what we demonize now. Take last year’s “Mama” and “The Conjuring.” Though quite good, both channeled our culture’s feminist backlash by indicting women who defy their “natural” maternal instincts. “The Babadook,” the debut feature from Aussie writer-director Jennifer Kent (expanded from her award-winning short “Monster”), may press that same bad-mommy button, but it does so with a great deal more insight and compassion – not to mention a crafty girl aesthetic. Imagine a movie hand-stitched by an Etsy queen or, better yet, a Bust Magazine editor, and we have some sense of what “The Babadook” brings to the table.

Amelia (Essie Davis) is a struggling single mother. With her salary as an eldercare nurse, she barely makes ends meet, and she’s still mourning her husband, who was killed en route to deliver their son, Sam (Noah Wiseman), now six years old. It doesn’t help that the kid is a handful. With his penchant for shrill tirades and handmade weapons, the hyperactive boy has been pulled out of school and alienated everyone in Amelia’s life. Even before a real monster descends upon their household, then, life is a nightmare – an effect captured in a recurring series of quick, rhythmically intercut shots that recall the drug montages of “All That Jazz” and “Requiem for a Dream.” (A clever association.) Click: child yanks mother from a deep sleep. Click: they peer under bed for monsters. Click: they peer in wardrobe for monsters. Click: mother reads child another bedtime story. This repetition of the mother-and-child routine is a soul-chilling metronome–one that’s especially unsettling because Amelia drones on in an exaggerated version of the impatient singsong every parent uses with a kid who just won’t go the f–k to sleep.

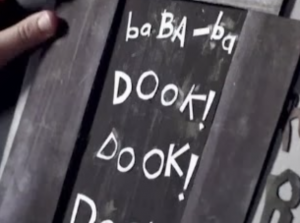

A pop-up book mysteriously materializes in Sam’s bedroom, and he demands she read it aloud. Black, white, and red, it is entitled Mr. Babadook, and it features an Edward Gorey-like oddbot sporting funny feet and a top hat who frightens and possesses them. Just what the doctor ordered for the already-high-strung Sam. But when Amelia tries to dispose of it, the book – you guessed it – rematerializes immediately. Life imitates art from there on in.

We have to admire a film that reveals its cards early in the game yet still scares the bejesus out of us. With references to early cinema and magic tricks, flashes of stop-motion animation, and a diorama-like design, “The Babadook” feels so much like a pop-up children’s book that it’s as if we’re stuck inside the monster’s world. Certainly Amelia’s soft voice, pink clothing, and mop of strawberry blond hair paint her as a fairytale heroine – which makes it all the more terrifying when she begins to growl at her son, “If you’re hungry, why don’t you eat shit?” (Besides Naomi Watts, Davis is the only actor around who can change her looks, even her coloring, within the same shot. Is this an Australian thing?)

All along, with his shrieks, wild eyes, askew jaw, spastic limbs, the child has seemed possessed but we begin to wonder if the Babadook is actually springing from the mother. Who can blame her? Even in the best of circumstances, most parents tread a fine line between resenting and loving their kids, and these circumstances are pretty bad. Her home-made tee shirt would read: My husband died on the way to the maternity ward, and all I got was this lousy tyke.

Lest we think this film is unsympathetic to the modern mother’s plight, small touches suggest a second-wave feminist agenda: Most of the horror takes place in the kitchen, where an infestation of roaches swarm out of the wall and glass appears in the soup. (Recall the old Marge Piercy quote: Burning dinner is not incompetence but war!) When cautioning Amelia against overmedicating Sam, a pediatrician says, “Most mothers aren’t keen on these sedatives.” (What about fathers, doc?) When Amelia gets in a car accident, another driver bellows, “And you’ve got a kid in the backseat!” We get it – oh, boy, do we get it: Everybody blames the mom! (Somewhere, Freud is nodding emphatically.) By the time Amelia cracks, it is at a (shudder) kid’s birthday party, where her fury is directed at a flock of perfectly coiffed, well-off Stepford moms who identify with “disadvantaged women” because they also “don’t always have time to go to the gym.” Hats off to Kent for tackling the intersection of economics and gender, a topic few are willing to address these days.

Such subversion is why “The Babadook” works so well. For all its otherworldly flourishes, it confirms that the most terrifying monsters are remarkably local – domestic, even. Finally, a horror movie has been made for DIY women everywhere.

This review originally was published in Word and Film.