I have seen “Selma,” Ava DuVernay’s remarkable portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. and the three Alabama marches that inspired the 1965 Voting Rights Act, at two press screenings. The first took place in November, and I wept so copiously that I felt it my duty to see the film again in order to write about it objectively.

I have seen “Selma,” Ava DuVernay’s remarkable portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. and the three Alabama marches that inspired the 1965 Voting Rights Act, at two press screenings. The first took place in November, and I wept so copiously that I felt it my duty to see the film again in order to write about it objectively.

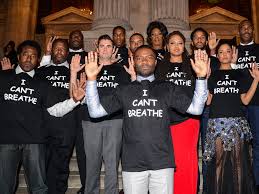

The second screening was held in mid-December. Common was still rapping, “That’s why we walk through Ferguson with our hands up” over the closing credits as I emerged into a Times Square filled with protestors. Some were silently standing in front of the police station; others were holding signs reading “I Can’t Breathe,” a reference to Eric Garner’s final words as he was choked to death by a cop. For a minute I felt like I was in the film itself, and that’s when I got it: There’s no objective way to see “Selma,” and that’s how it should be. King may have prescribed peaceful protest but he also stated adamantly that there is no neutrality when it comes to the issue of civil rights.

The only man from the twentieth century who has an American federal holiday named after him, Martin Luther King Jr. is almost inarguably our country’s most influential civil rights leader to date. Yet, as improbable as it may seem, “Selma” is the first feature-length film ever made about him. Wisely, DuVernay and screenwriter Paul Webb don’t compensate by covering the entire arc of King’s life. Instead, they pick up right where a more traditional King biopic might have ended: when awards have already been bestowed but important work is left to be done.

Opening scenes lay this out elegiacally, juxtaposing King’s 1964 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech with images of the Birmingham Church Bombing – the words “I accept this for our lost ones” floating in our ears as lace and young African American girls’ limbs float in rubble. Still reeling, we shift to Annie Lee Cooper (Oprah Winfrey), her face a furiously blank mask as a sneering Selma, Alabama, clerk thwarts her attempt to register to vote. We then move to the Oval Office, where King (David Oyelowo) is wrangling with President Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) about the urgency of voting rights for Southern blacks. With a hand on King’s shoulder (proprietary pats holding such queasy historical significance in our country), the president says the movement should wait its turn while he fights the “war on poverty.” King rejoins his advisers waiting for him outside, tips his hat, and says, “Selma it is.

It’s such a subtly bad-ass moment that, both times I’ve seen the film, I’ve gotten chills. In 1965, although the 1964 Civil Rights Act had legally desegregated the South, many towns like Selma were clinging to Jim Crow discrimination. White officials determined to preserve their hegemony were going to every length to prevent black citizens from registering to vote, and with George Wallace (Tim Roth) as Alabama governor, state-mandated change seemed unlikely. Social dissidence was the only real option, and King, whose perspicacity is highlighted here, knew that protests would only be effective if they garnered national sympathy, especially from white America. In subsequent scenes we see how he selects Selma (it had a retrogressive sheriff who was likely to get so ugly that the nation would take note), as well as how he directly if respectfully confronts local grassroots organizations and elected officials including, yes, the president.

Recent films “The Imitation Game” and “The Theory of Everything” have focused on important men’s Achilles’ heels. “Selma” takes a different tack, balancing the intimate and the epic by only incorporating the personal details relevant to this chapter in the civil rights movement. King’s extramarital affairs, for example, are solely introduced in the context of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover’s attempts to discredit him as a husband and as a leader; no tawdry sex scenes or looks of longing here. The civil rights leader is not presented as a saint so much as a flawed human who, by the time the events of this film commence, behaves as an instrument of something greater than himself.

As King, Oyelowo delivers a performance that feels genuinely received. It is rumored that he prayed before every take, and whether or not that’s literally true, it could be. He is calm, focused, and almost unnervingly still, with thoughts visibly flashing over his features that never devolve into the “indicating” that dooms lesser actors. This King is constantly calibrating the most efficient use of his energy; only in front of a podium does he fully come alive, and the effect is awe-inspiring every time. He has united himself so wholly with the movement that we can’t imagine him anywhere but at the front of a pivotal struggle, aided almost entirely by black brothers and sisters like fellow activists James Bevel (Common), Reverend Hosea Williams (Wendell Pierce), and Amelia Boynton (Lorraine Toussaint). Very few scenes in cinema history offer such in-depth, finely tuned primers in political strategy; the full names of organizations like Southern Christian Leadership Conference are even included, rather than their acronyms. What’s not included are any central white “allies,” an omission that only strengthens the quiet radicalism that is this film’s calling card as well as King’s. (Unfortunately, it also may explain the film’s many delays and the fervor about its alleged historical inaccuracies though, as Vox’s Matthew Yglesias has written, that a film should be ruled out for “having the temerity to focus on black people’s agency in securing their own liberation is completely absurd.” )

As King, Oyelowo delivers a performance that feels genuinely received. It is rumored that he prayed before every take, and whether or not that’s literally true, it could be. He is calm, focused, and almost unnervingly still, with thoughts visibly flashing over his features that never devolve into the “indicating” that dooms lesser actors. This King is constantly calibrating the most efficient use of his energy; only in front of a podium does he fully come alive, and the effect is awe-inspiring every time. He has united himself so wholly with the movement that we can’t imagine him anywhere but at the front of a pivotal struggle, aided almost entirely by black brothers and sisters like fellow activists James Bevel (Common), Reverend Hosea Williams (Wendell Pierce), and Amelia Boynton (Lorraine Toussaint). Very few scenes in cinema history offer such in-depth, finely tuned primers in political strategy; the full names of organizations like Southern Christian Leadership Conference are even included, rather than their acronyms. What’s not included are any central white “allies,” an omission that only strengthens the quiet radicalism that is this film’s calling card as well as King’s. (Unfortunately, it also may explain the film’s many delays and the fervor about its alleged historical inaccuracies though, as Vox’s Matthew Yglesias has written, that a film should be ruled out for “having the temerity to focus on black people’s agency in securing their own liberation is completely absurd.” )

At one point, notoriously hamstrung Lee Daniels (“The Butler,” “Precious”) was slotted to direct “Selma,” and I thank the heavens he didn’t. Shot on location in the real Selma, even the most violent events are elegantly staged here, and cinematographer Bradford Young photographs the heavily guarded Edmund Pettus Bridge over which protestors marched as the austere military rampart it then resembled. (Young also knows how to light black actors, which is a rarer skill than it should be.) Nothing, not even an obtrusive soundtrack, detracts from the impact of these black men and women filling the screen with their silent, shoulder-to-shoulder marches. I get a lump in my throat every time I recall their beautiful, unadorned resistance.

We are now in the early days of 2015. It is fifty years since the 1965 Voting Rights Act was passed, and people like Chief Justice John Roberts claim aspects of it are now “obsolete.” But economically depressed, racially stratified areas like Detroit and post-Katrina Louisiana, new voter ID laws that marginalize black voters, efforts to delegitimize our first black president, and police killing of unarmed black men like Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Tamir Rice suggest otherwise.

As protests continue to erupt across the country, it becomes ever more apparent that we need models of effective change. Both timely and timeless, “Selma” fits that bill stirringly. This is not a traditional prestige biopic. It is not even a mere film. Rather, it is an expertly rendered, deeply resonant blueprint.

This was originally published in Word and Film.