In Kate Bolick’s wonderful new book Spinster, she meditates on the possibilities of an adult female life undefined by others. “The spinster wish was my private shorthand for the novel pleasures of being alone,” she writes. “Whether to be married or to be single is a false binary. The space in which I’ve always wanted to live… isn’t between those two poles but beyond it.” Her point–a vital one–is that here in the twenty-first century women should no longer be viewed through the lens of their attachment to others. (Remember that men remain “misters” their entire adult lives, regardless of their age or marital status.)

In Kate Bolick’s wonderful new book Spinster, she meditates on the possibilities of an adult female life undefined by others. “The spinster wish was my private shorthand for the novel pleasures of being alone,” she writes. “Whether to be married or to be single is a false binary. The space in which I’ve always wanted to live… isn’t between those two poles but beyond it.” Her point–a vital one–is that here in the twenty-first century women should no longer be viewed through the lens of their attachment to others. (Remember that men remain “misters” their entire adult lives, regardless of their age or marital status.)

We need only to look at cinema to realize how far we are from a world in which, as Bolick puts it, a woman is “free to consider the long scope of her life as her distinct self.” Put simply, women in films are never contentedly unattached. They may be single– but tragically or darkly comically so, as if they’re suffering from a condition that requires treatment. And make no mistake: that treatment is almost always a relationship. Hollywood is built upon the twin tenets of big guns and big love, and it’s generally uncomfortable with ambiguity, especially when it comes to single ladies. Happy endings–the glamorous finality of “Jack shall have his Jill”–are what the movie doctor ordered. Unattached women are either Bridget Jones types—not-so-hot messes who must be rescued by modern Mr. Darcys—or dangerously untamed women who must die, as Glenn Close does in “Fatal Attraction” and Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon do in “Thelma and Louise.” Far, far less common are films that conclude with women who are joyously, consciously unattached–not as a last-ditch solution to a toxic romance (“Heathers”) or a love triangle (“St Elmo’s Fire,” “Broadcast News”) but as an active choice to live independently.

Consider these rare birds:

“My Brilliant Career” (1979)

Judy Davis disavows this film now but her portrayal of Sybylla, the aspiring writer who refuses her beau’s proposal of marriage to achieve her dreams of becoming a published author, was revelatory for a generation of women. Directed by Gillian Armstrong (“Little Women,” “Mrs. Soffel”), this 1890s-set period drama equates sweeping Aussie vistas with sweeping female autonomy, and never apologizes for its audacity.

“Lola Versus” (2012)/”Frances Ha” (2012)

Fair or not, I’m counting these two films as one. They were released the same year; they star Greta Gerwig; they are quirky indies about a twentysomething bohemian learning to stand on her own two feet. Though “Frances Ha” boasts more cinematic value–it doubles as director Noah Baumbach’s homage to the French new Wave—“Lola Versus,” directed by Generation Whine advocate Daryl Wein, more consciously honors female independence. Really, it’s an embarrassment of riches; in both, Barnard graduate Gerwig (who co-wrote “Frances Ha”) admirably tackles the realities of a millennial woman living on her own terms.

“Brave” (2012)

Laugh if you wish, but lately Disney’s been a lot more progressive than the rest of Hollywood when it comes to the “women question.” In this Pixar animated feature, Kelly Macdonald voices Merida, a Scottish princess who defies her country’s custom by refusing to marry. Sure, she mistakenly transforms her retrogressive mother (voiced by Emma Thompson) into a bear, but in the end, armed with her trusty crossbow, she rescues everyone, including herself. A beautiful “fish without a bicycle” film for girls (and boys) of all ages.

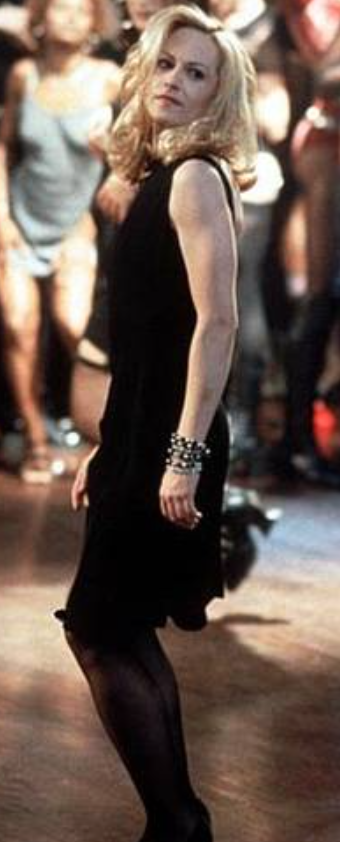

“Living Out Loud” (1998)

Few saw this rueful comedy written by and directed by the underrated Richard LaGravenese (“The Last Five Years”) yet it’s an unparalleled anthem of female “aloneliness.” Starring Holly Hunter at her most willfully bittersweet, it sympathetically depicts the self-discovery of a Manhattan divorcee against a downtown backdrop of martini bars, Alphabet City alleys, and glittering jazz numbers sung by Queen Latifah as a nightclub singer with a closet full of satin dresses. The final scene, in which Hunter sashays alone down the street while singing Sly and the Family Stone’s “Hot Fun in the Summertime,” offers cinema’s second most iconic image of single ladyhood. The first most iconic image can be found in….

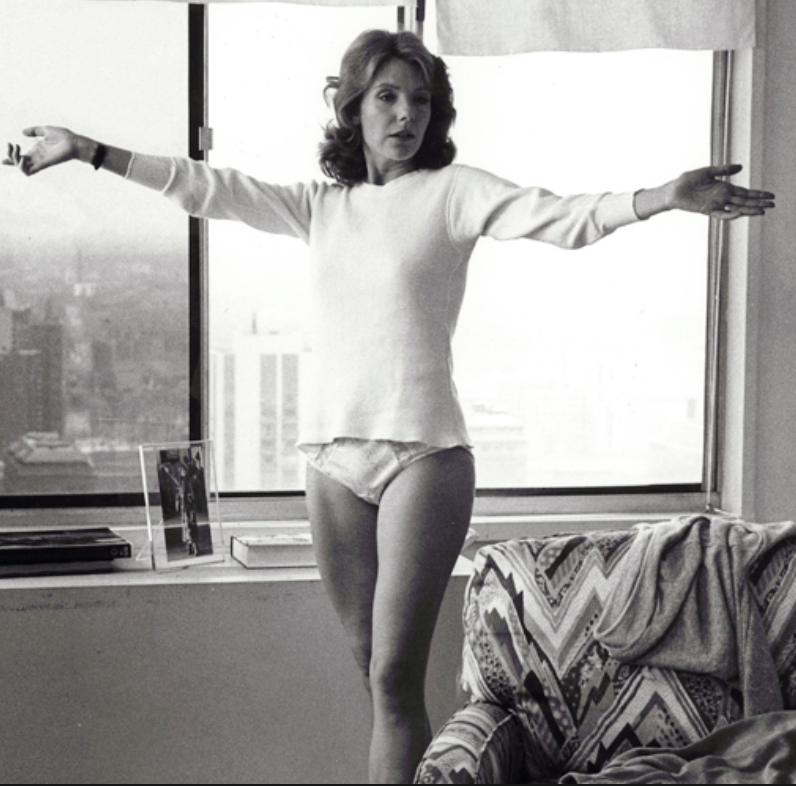

“An Unmarried Woman” (1978)

Directed by Paul Mazursky, that king of mise en scène, this stars Jill Clayburgh as a recently separated New York mother trying out therapy, consciousness-raising groups, and casual sex in a quest for a shag-carpeted room of her own. The late Mazursky–and, for that matter, Clayburgh–had a knack for mocking self-exploration without malice, and this film offers a time capsule not only of I’m-OK-You’re-OK NYC folly but of that moment in which women’s liberation offered mainstream women genuine alternatives. The film ends with Clayburgh wobbling through the streets of Soho, wielding an enormous painting given to her by a beau whom she’s just left. Iconic, indeed.

This was originally published in Word and Film.