“Ex Machina,” the much-anticipated directorial debut from British screenwriter Alex Garland (“Sunshine,” “28 Days Later”), is brimming with big ideas. About a mogul and his robot, it tackles the construction of gender, sexual desire, and artificial intelligence with a sleek, Scandinavian design that transcends a modest budget but buckles under its own ingenuity–like a dystopian thriller made by those kids at Ikea.

“Ex Machina,” the much-anticipated directorial debut from British screenwriter Alex Garland (“Sunshine,” “28 Days Later”), is brimming with big ideas. About a mogul and his robot, it tackles the construction of gender, sexual desire, and artificial intelligence with a sleek, Scandinavian design that transcends a modest budget but buckles under its own ingenuity–like a dystopian thriller made by those kids at Ikea.

Domhnall Gleeson, contemporary cinema’s favorite ginger-haired everyman, plays Caleb, a 24-year-old coder for Bluebook, a Google-like Internet company, who wins a lottery prize to spend a week with Nathan (Oscar Isaac), the company’s reclusive founder and CEO. It’s no coincidence that Gleeson has also starred in a key episode of “Black Mirror,” the sly, slightly futuristic BBC series about the dangers and delights of technology; in his brief career, the clever Irishman has already established himself as the reigning shorthand for male vulnerability, a topic consuming contemporary science fiction (and, not so subtly, Garland himself).

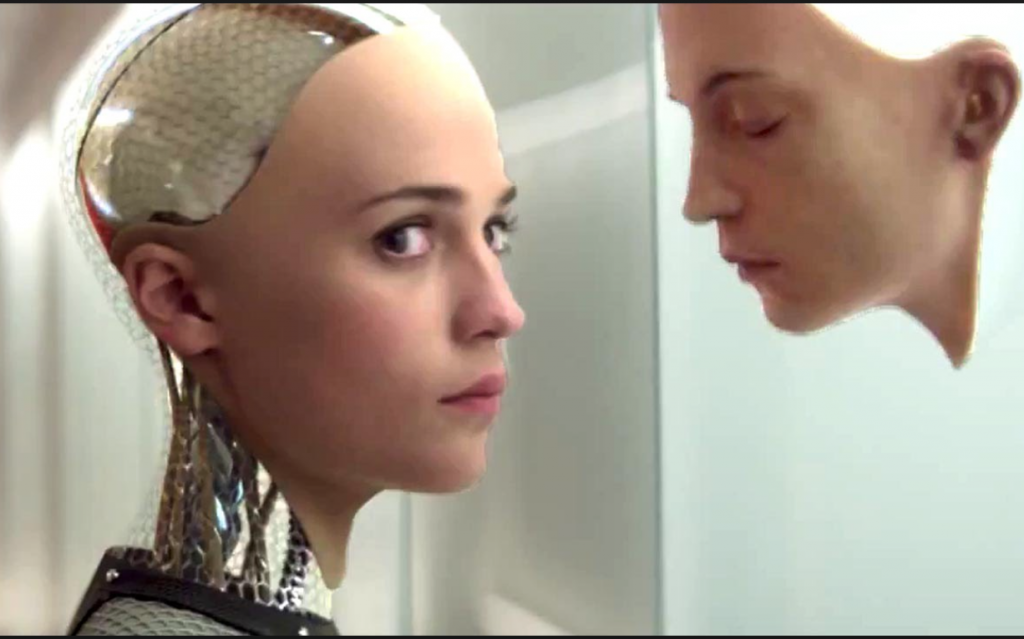

Less a nebbish than a new-age Neanderthal, Nathan is a vodka-and-wheatgrass-swilling boxer who perches alone in an Alaska mountain retreat so glamorously isolated that Caleb, who is conveyed to the area by helicopter, has to trek the last mile or so by foot–the perfect way to set him off-kilter from the get-go. Caleb is the Charlie Bucket to Nathan’s Willy Wonka, who has planted this golden ticket to introduce the younger man to his latest invention, a female-gendered robot named Ava (Alicia Vikander). Caleb’s task: to perform a Turing test that will determine whether Ava’s thinking and behavior differs from that of a human being–and if so, where the distinction lies. To force Caleb to focus on her behavior rather than her appearance, Nathan leaves Ava’s body–a see-through symphony of wires, mesh, and sparks– unadulterated though he gives her the face of a Swedish model.

A rhythm is quickly established, in which Caleb quizzes the seemingly placid Ava during the day, and gets wasted each night with Nathan. But mystery looms–in the oddly windowless bunker, in the electricity that keeps flickering, in Nathan’s unsmiling asides, and in his mutely subservient aide Kyoko (Sonoya Mizuno). It’s a duck-and-parry, in which Caleb tries to earn his keep–“I’m hot on high-level abstraction,” he boasts–and Nathan throws him bones– “You’re good with words, you’re quotable” –before sinking him with brutal ego blows that Caleb, orphaned in childhood, especially registers.

Without Ava, their dance would be nothing; there’s nothing like a traffic-in-woman paradigm to keep a bromance afloat. Moving with audible whirs and an exaggerated grace, she gently flirts with Caleb, the first human male she’s met aside from her maker. Caleb is at first askance–“is she programmed to do that?”–but bonds with her nonetheless, especially as he begins to suspect Nathan may be Machiavellian enough to create females just so he can control them. Why doesn’t Kyoko talk? Why can’t Ava leave the room in which she resides? Why does Nathan destroy all her artwork? Of course, it’s Ava herself who plants these bees in Caleb’s bonnet, whispering cryptic messages in his ear and batting her dark fringe of lashes. When she slowly covers her clear-plastic limbs and torso with an ingénue’s uniform of woolen tights and flowered dress, it’s as seductive as another woman’s strip-tease. It’s no wonder the two, both subjects in a madman’s domain, soon hatch an escape plan while shyly studying each other’s mouths. What isn’t clear is how much their alliance is also of Nathan’s design.

As with all of Garland’s scripts, this film stumbles in its third act, betraying an intellectually and ideologically ambitious premise with a conventionality that, to be fair, may not bother some. With her unblinking, ever-vigilant composure, Vikander is impressively slinky–she’s a star in the making–but the promise of Ava is too big for this movie’s old-fashioned britches.  And it’s time we acknowledged Oscar Isaacs is not an ideal movie actor. Julliard-trained, he suffers from an excess of gravitas (who knew such a malaise could strike a modern Hollywood actor?); like a black hole, he sucks the life out of everything in which he appears. Here, his Nathan functions as a one-man plot spoiler, better suited to the conclusion than the initially light-footed interrogations. Too aptly titled, “Ex Machina” morphs into that most clichéd, if admittedly appealing, of recent genres: a sci-fi noir, complete with a femme fatale for the new millennium.

And it’s time we acknowledged Oscar Isaacs is not an ideal movie actor. Julliard-trained, he suffers from an excess of gravitas (who knew such a malaise could strike a modern Hollywood actor?); like a black hole, he sucks the life out of everything in which he appears. Here, his Nathan functions as a one-man plot spoiler, better suited to the conclusion than the initially light-footed interrogations. Too aptly titled, “Ex Machina” morphs into that most clichéd, if admittedly appealing, of recent genres: a sci-fi noir, complete with a femme fatale for the new millennium.

This was originally published in Word and Film.