While it may be hard to believe that Larry Clark’s “Kids” just celebrated its twentieth anniversary, it’s not hard to believe that “Metropolitan” is turning twenty-five. Even at the time of its 1990 release, writer/director Whit Stillman’s inaugural feature about New York debutantes and their male escorts seemed to hail from another era. As a carefully worded eulogy for an American social caste, this was its whole point; these protagonists were so anachronistic that their courtships consisted of debates about Jane Austen, whose blithe-as-a-heart-attack formulations of romantic love proved an apt model for the film itself.

While it may be hard to believe that Larry Clark’s “Kids” just celebrated its twentieth anniversary, it’s not hard to believe that “Metropolitan” is turning twenty-five. Even at the time of its 1990 release, writer/director Whit Stillman’s inaugural feature about New York debutantes and their male escorts seemed to hail from another era. As a carefully worded eulogy for an American social caste, this was its whole point; these protagonists were so anachronistic that their courtships consisted of debates about Jane Austen, whose blithe-as-a-heart-attack formulations of romantic love proved an apt model for the film itself.

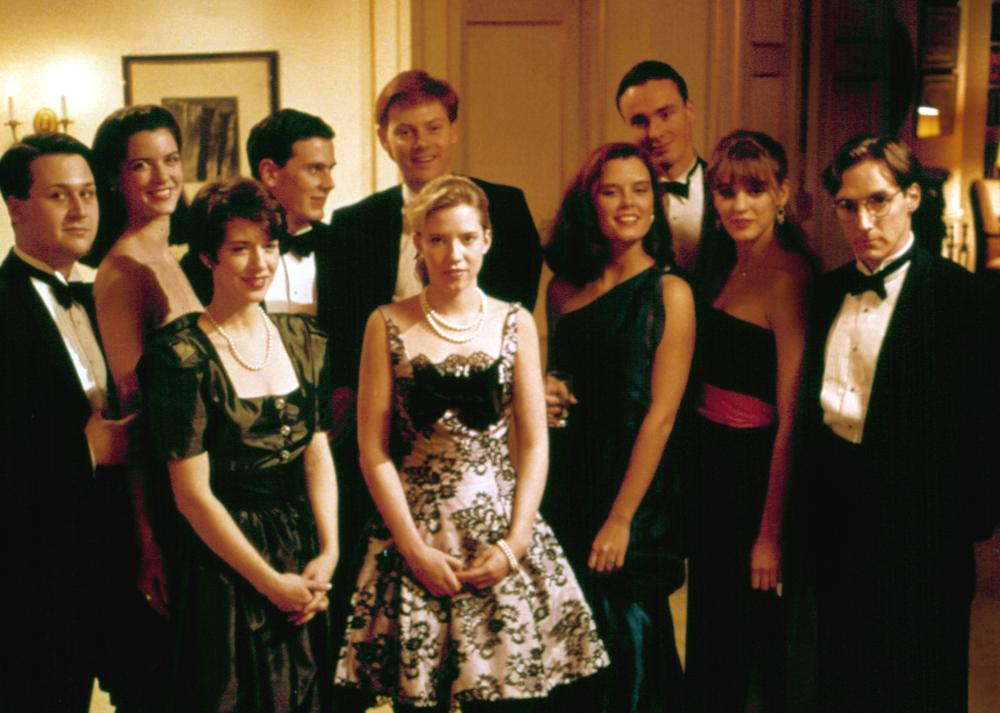

Though all of Stillman’s work focuses on the grave nostalgia of young people, only “Metropolitan” puts that concern front and center with a formality that is more literary than cinematic. With its unobtrusive Upper East Side interiors, unremarkable-looking cast (few of whom went on to pursue professional acting careers), and endless prattle about the decline of the “Urban Haute Bourgeoisie” (a term one character devises to describe the “preppy class”), this film highlights the life of the mind as no other American coming-of-ager had done before and likely ever will again. The story is told from the alternating perspectives of Audrey Rouget (Carolyn Farina), the most pensive member of her group, and Tom Townsend (Edward Clements), an Ivy League ginger who has lost his trust fund and must, relatively speaking, live on his wits. (This entails him living on the Upper West Side and declaring himself an agrarian socialist while buying a secondhand tux.)

The film begins as a weeping Audrey rushes down an apartment hallway, clad in a half-zipped meringue of a dress. She is not escaping a date rapist or on a drunken rampage; she’s just mortified because her brother has said the gown makes a “part of her anatomy look enormous.” The problem is solved easily enough. Her mother makes a few alterations while the girl waits, placated, in a long, satin slip. Against her bedroom’s floral wallpaper and primrose fireplace, she seems less neon princess than children’s storybook character. In the next scene, Audrey’s gaggle of barely collegiates accidentally sweep Tom into their cab, and, as easy as that, he becomes part of their crowd during the Christmas ball season. As group provocateur Nick Smith (Chris Eigeman) points out: “It’s the most economic social life you’ll find in New York.”

An easy rhythm develops, in which these young fuddy-duddies attend dances and then loll in evening attire at the apartment of Sally Fowler (Dylan Hundley), whose parents seem especially accommodating. It is discovered that Tom pines for Audrey and Sally’s boarding school mate Serena Slocum (Elizabeth Thompson), though Audrey is growing sweet on him. Charlie Black (Taylor Nichols), who admires Audrey, resents Tom for squandering her affections but Nick is too consumed by his hatred for Rick Von Sloneker (Will Kempe), a pony-tailed aristocrat cum Lothario, to work up any antipathy for Tom – especially when Von Sloneker seduces the girl Nick secretly has been bedding. Such are the low stakes of this slight comedy of manners. These old-money teenagers even discuss French philosopher Charles Fourier in politely constructed paragraphs as they (halfheartedly) play strip poker.

Audrey is drawn to Tom for his willingness to engage with her about literature, despite the fact that she finds his ideas amusingly wrongheaded. He dismisses Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park out of hand because critic Lionel Trilling deems it her worst book. “He said that the context of that novel, and nearly everything Austen wrote, is ridiculous from today’s perspective,” announces Fred, before adding that he has not bothered to actually read any Austen since he prefers literary criticism. Audrey smiles and responds in her high-pitched boarding school cadences: “Has it ever occurred to you that from Austen’s perspective everything looks even worse?” Consider that a missive from Whit Stillman’s pen to our ears.

Since this film takes cues from Lady Jane herself (this may be the best Austen adaptation that’s never been acknowledged as such), Tom learns that the deeper virtues of modest Audrey are preferable to Serena’s more obvious assets. (He also, needless to say, comes around on Austen herself.) But first he and Charlie unite in their quest to determine the fate of the UHB. “Are people from our background doomed to failure?” Charlie asks an older member of their set at a midtown bar, and the man considers the question while ogling his drink. “Doomed would be far easier,” he replies.  “We fail without being doomed.” Perhaps that is the true thesis sentence here, as well as the one we’d most likely encounter in an Austen novel.

“We fail without being doomed.” Perhaps that is the true thesis sentence here, as well as the one we’d most likely encounter in an Austen novel.

Decades before this country’s middle class really fell out, this film anticipated that a “leisure class” – a gently wealthy people who presumed moral and aesthetic superiority – was not long for this world. With what turned out to be a characteristic mix of generosity and priggishness, Stillman tipped his top hat at Austen who, centuries before that, had not only anticipated this decline but, in her slyly persistent themes of marriage and money, suggested it was for the best. “Metropolitan” was a swan song of a debut, and nothing could have heralded the beginning of an end with a headier panache.

This was originally published in Word and Film.