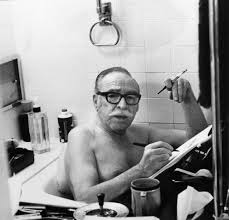

Dalton Trumbo may not be well-known today but at the height of the Hollywood Red Scare he was a household name. The author of the National Book Award-winning novel Johnny Got His Gun (1939), he was a former war correspondent who, in the 1940s, became one of the country’s highest-paid screenwriters. (Credits include “Spartacus” and “Exodus.”) He was also an outspoken member of the American Communist Party, which raised the hackles of the Joseph McCarthy-led House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) during the 1947 investigation of Communist influences in the motion picture industry. Trumbo soon became one of the “Hollywood Ten” – a group of screenwriters and filmmakers who, upon refusing to testify in Congress, served one-year prison sentences and were subsequently blacklisted for more than a decade from working for any movie studio. Still, he won two Academy Awards while blacklisted – one was originally given to a front writer, and the other was awarded to “Robert Rich,” Trumbo’s pseudonym – and, after the ban was lifted in 1960, received official credit for both: “Roman Holiday” and “The Brave One.” He died at age seventy, a vindicated man.

Dalton Trumbo may not be well-known today but at the height of the Hollywood Red Scare he was a household name. The author of the National Book Award-winning novel Johnny Got His Gun (1939), he was a former war correspondent who, in the 1940s, became one of the country’s highest-paid screenwriters. (Credits include “Spartacus” and “Exodus.”) He was also an outspoken member of the American Communist Party, which raised the hackles of the Joseph McCarthy-led House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) during the 1947 investigation of Communist influences in the motion picture industry. Trumbo soon became one of the “Hollywood Ten” – a group of screenwriters and filmmakers who, upon refusing to testify in Congress, served one-year prison sentences and were subsequently blacklisted for more than a decade from working for any movie studio. Still, he won two Academy Awards while blacklisted – one was originally given to a front writer, and the other was awarded to “Robert Rich,” Trumbo’s pseudonym – and, after the ban was lifted in 1960, received official credit for both: “Roman Holiday” and “The Brave One.” He died at age seventy, a vindicated man.

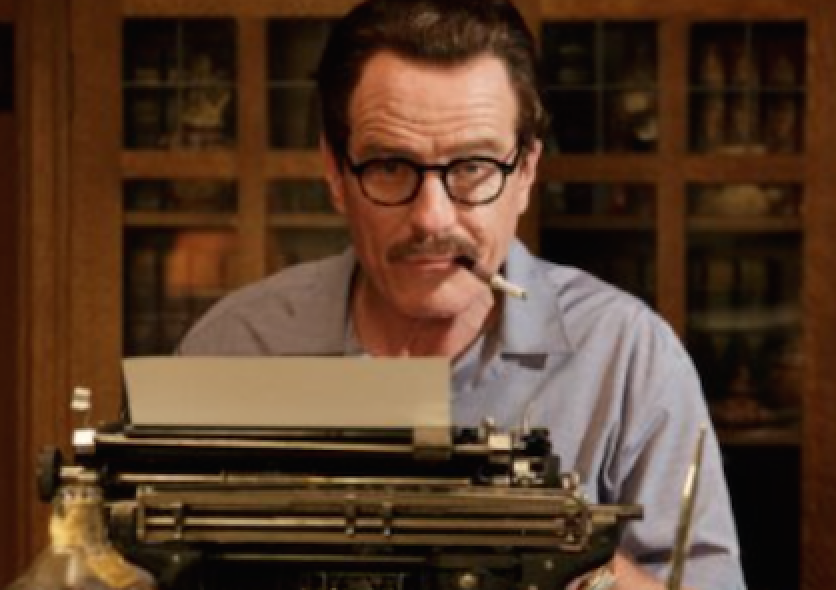

Trumbo’s story is one of the few Hollywood tales that actually deserves to be made into a movie (though many more are), and “Trumbo,” directed by Jay Roach and adapted by John McNamara from Bruce Cook’s biography, is duly a study in Tinseltown razzle-dazzle, complete with gorgeous costumes and set designs, original film footage, zinging one-liners, and enough hokum to hurt our teeth even as we’re pumping our fists in the air. Bryan Cranston stars, and it’s his first endeavor since “Breaking Bad” that makes good use of his character-actor charisma in a leading role. When he’s not playing for the cheap seats with big, meaty speeches, he’s writing in bathtubs with cigarette holders clamped between his teeth and glass tumblers of scotch by his side; the succession of his shiny manual typewriters is enough to make us long for Hollywood’s golden era, warts and all.

Roach is just the guy to tackle such a project. His resume is studded with an odd combination of political dramedies like “Recount,” “Game Change,” and “The Campaign,” and such high-voltage dumb comedies as the “Austin Powers” films and “Meet the Parents.” For this film, he draws upon his experience in both genres with an enthusiasm that sometimes gets ahead of itself though never obnoxiously so. This Trumbo crackles with all the hot confidence of the characters he wrote, and it’s not hard to imagine how he rallied his colleagues into thumbing their noses at Congress or snagged Cleo (Diane Lane), his sweet-faced, stalwart sidekick of a wife. Nor is it hard to imagine how he ignited the ire of commie witch hunters Hedda Hopper (Helen Mirren, with punctuation marks for eyebrows and an enviable array of hats) and John Wayne (David James Elliott). In an early highlight, Trumbo takes down the grandstanding actor by reminding him he spent World War II “stationed on a film set, wearing makeup, shooting blanks.” Bada-bing, bada-boom!

Roach is just the guy to tackle such a project. His resume is studded with an odd combination of political dramedies like “Recount,” “Game Change,” and “The Campaign,” and such high-voltage dumb comedies as the “Austin Powers” films and “Meet the Parents.” For this film, he draws upon his experience in both genres with an enthusiasm that sometimes gets ahead of itself though never obnoxiously so. This Trumbo crackles with all the hot confidence of the characters he wrote, and it’s not hard to imagine how he rallied his colleagues into thumbing their noses at Congress or snagged Cleo (Diane Lane), his sweet-faced, stalwart sidekick of a wife. Nor is it hard to imagine how he ignited the ire of commie witch hunters Hedda Hopper (Helen Mirren, with punctuation marks for eyebrows and an enviable array of hats) and John Wayne (David James Elliott). In an early highlight, Trumbo takes down the grandstanding actor by reminding him he spent World War II “stationed on a film set, wearing makeup, shooting blanks.” Bada-bing, bada-boom!

We zip through Trumbo’s trials, ideological convictions, and prison sentence surprisingly speedily (perhaps too speedily), dwelling instead on his struggles to regain footing in Hollywood. Trumbo was forced to write cheapo scripts under pseudonyms for B-movie producer Frank King (John Goodman, in deliciously broad strokes). The story stumbles most when focusing on the toll taken on his family, partly because the ever-impassive Dakota Fanning is woefully miscast as his purportedly crackerjack daughter Nikola and partly because the dialogue wades into soggy territory in these scenes. But every time the film begins to sound and look like a pallid imitation of something Trumbo himself would write – every time we begin to tire of his unflagging stream of inspirational speeches and witty comebacks – it admirably pulls back its own curtain.

As fellow blacklisted screenwriter Arlen Hird, Louis C.K. essentially plays himself (he always does in films) but he’s tapping into the earnest, doleful strain of his personality that grounds out the poop jokes in his TV series and, in fact, all the poop everyone’s spouting here. About Trumbo’s red-shirt proclamations, Hird says: “I don’t trust what you say because you still live like a rich man.” Though we could similarly dismiss this film, it works past our defenses anyway. In a final scene, when a time-torn Trumbo accepts a lifetime achievement award and forgives his tormenters, his glibness may finally be shed but his lily remains gilded. Now that’s entertainment.

As fellow blacklisted screenwriter Arlen Hird, Louis C.K. essentially plays himself (he always does in films) but he’s tapping into the earnest, doleful strain of his personality that grounds out the poop jokes in his TV series and, in fact, all the poop everyone’s spouting here. About Trumbo’s red-shirt proclamations, Hird says: “I don’t trust what you say because you still live like a rich man.” Though we could similarly dismiss this film, it works past our defenses anyway. In a final scene, when a time-torn Trumbo accepts a lifetime achievement award and forgives his tormenters, his glibness may finally be shed but his lily remains gilded. Now that’s entertainment.

This was originally published in Word and Film.