When it comes to movie adaptations, this year was such an embarrassment of riches that making a top-ten list of best adaptations proved a tough task – if also a fun one. (No one’s ever going to pity a film critic for having to revisit movies she loves.) Of course, every top-ten list is sure to enrage as many people as it pleases, so read on and then tell me: What would be on your list of best 2015 adaptations? Here’s what I have on mine.

10) “45 Years”

10) “45 Years”

Amid all the “Exotic Marigold Hotel”-style films about the Endearing Habits of Elders comes this shadowy and formidably honest portrait of an aging couple who discover they may not know each other as well as they’d thought. Sixties icons Tom Courtenay and Charlotte “The Look” Rampling star in this deft adaptation by screenwriter/director Andrew Haigh (“Weekend,” “Looking”) of David Constantine’s short story “In Another Country.” A final scene comprises the best minute of acting in 2015 cinema.

9) “Carol”

9) “Carol”

Adapted from Patricia Highsmith’s groundbreaking 1952 novel, director Todd Haynes’s latest film is easily the most hopeful love story of the year. Cate Blanchett stars as a married socialite with red lipstick to match her talons; all kewpie doll eyes and tiny pouts, Rooney Mara plays the shopgirl with whom she has an affair. Though this at times devolves into a Douglas Sirk museum, it also is a stunningly rendered paean to the courage that intimacy universally requires.

8) “The End of the Tour”

8) “The End of the Tour”

Though it may prove less satisfying to ardent fans of the late author David Foster Wallace, this adaptation of David Lipsky’s book, Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, about a five-day interview he conducted with the Infinite Jest author, offers flashes of insight that far outstrip its source material. Starring Jason Segel as Wallace and Jesse Eisenberg as Lipsky in a feat of casting that’s almost too on the nose, it it is directed by James Ponsoldt (“The Spectacular Now,” “Smashed”), who excels at exposing self-delusions with the gentlest of bedside manners.

7) “Beasts of No Nation”

7) “Beasts of No Nation”

About a boy orphaned by rebel forces in an unnamed country, this adaptation of Nigerian-American Uzodinma Iweala’s fiercely economical 2005 debut novel is an extraordinary allegory about the machinery of human violence. It is also the most assured film to date from gifted screenwriter, director, and cinematographer Cary Joji Fukunaga (“True Detective,” “Jane Eyre”), perhaps because he’s best when addressing crimes against children. As a grizzled, sexually conflicted commander, Idris Elba channels the chilling farrago of paternalism and pathology with which he portrayed drug lord Stringer Bell of the HBO series “The Wire.”

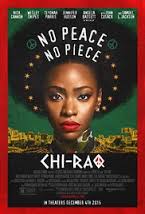

6) “Chi-Raq”

6) “Chi-Raq”

The most controversial film on this list is also one of the few that dares address contemporary social issues with zig-zagged flair. A loose-as-a-goose adaptation of Aristophanes’s “Lysistrata,” Spike Lee’s latest (he co-writes and directs) tackles contemporary Chicago gang violence; the title references the fact that the number of the city’s homicides surpasses the number of American soldiers dead in Iraq. Some take issue with how the female characters are saddled with the moral responsibility of their community (the girlfriends of gang members organize a sex strike for peace); others feel Lee is making light of serious urban blight. I think it’s a genius if wild-eyed spoken-word musical that gets much more right than it gets wrong: It’s ragged and binary for sure, but also colorful in every way our culture needs right now.

5) “Far From the Madding Crowd”

5) “Far From the Madding Crowd”

Leave it to former Dogme 95 director Thomas Vinterberg to deliver the finest – and least sentimental – period drama of the year. With feminist grit and lush cinematography, this adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s love quadrangle does justice to the glorious complexity of Bathsheba Everdene (Carey Mulligan), a nineteenth-century literary heroine so legendarily independent that Suzanne Collins named the protagonist of The Hunger Games after her.

4) “Brooklyn”

4) “Brooklyn”

This tale of a 1950s Irish girl (the inimitable Saoirse Ronan) who moves to America but feels the pull of her homeland captures all the nuance of Colm Tóibín’s 2009 antecedent novel without resorting to any of the clichés that can doom immigration sagas. Swoony and sincere, it boasts so much old-fashioned charm that you can just imagine its characters plunking down fifty cents to see it.

4)”The Martian”

Ridley Scott’s big-budget, man-versus-nature epic about an astronaut/botanist (Matt Damon) whose survival hinges upon his ability to “science the shit” out of being stranded on Mars is based on a self-published novel by programmer Andy Weir, who actually built his own computer simulation of orbital trajectories to ensure a high level of accuracy. What’s most matter-of-factly miraculous: The race-against-the-clock thriller’s swashbuckling saviors are physicists, engineers, and chemists sweating over calculations rather than swordfights. In this film, the geeks have inherited not just the earth but the entire solar system.

Ridley Scott’s big-budget, man-versus-nature epic about an astronaut/botanist (Matt Damon) whose survival hinges upon his ability to “science the shit” out of being stranded on Mars is based on a self-published novel by programmer Andy Weir, who actually built his own computer simulation of orbital trajectories to ensure a high level of accuracy. What’s most matter-of-factly miraculous: The race-against-the-clock thriller’s swashbuckling saviors are physicists, engineers, and chemists sweating over calculations rather than swordfights. In this film, the geeks have inherited not just the earth but the entire solar system.

2) “The Big Short”

2) “The Big Short”

It’s a fine line between wisecracker and wiseman, and in crafting this fictionalized account of the 2008 worldwide economic meltdown, “Talladega Nights” director Adam McKay toes it brilliantly. Christian Bale, Ryan Gosling, Steve Carell, and Brad Pitt (who doubles as co-producer) star as finance guys who figure out how to profit from the collapse of the American housing bubble; by tracing their path, this charismatic and powerfully useful agitprop based on Michael Lewis’s 2010 bestseller seduces us the way Americans have been seduced by their own greed.

1) “Room”

1) “Room”

That no one thought Emma Donoghue’s 2010 novel about a woman and son confined in a tiny, sound-proof garden shed could be translated to screen makes this adaptation (also written by Donoghue) all the more impressive. Starring a wondrously feral Brie Larson, this two-act film is best experienced as the allegory of an era in which we are rapidly recalibrating our understanding of space, self-reliance, and intimacy. Like all the best fables, its meanings will continue to emerge for years to come; for now it most effectively suggests how our attachments both impair and secure our spiritual freedom.

This was originally published in Word and Film.