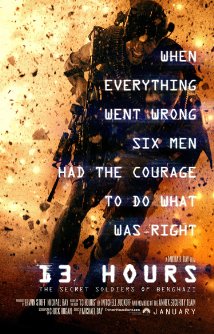

These days, Michael Bay is best known for his seemingly endless stream of “Transformer” movies but he’s also this country’s most unabashedly pro-military director; since “Pearl Harbor” (2001), he has demonstrated an enthusiasm for artillery-laden features whose guiding principle seem to be “Keep it butch, boy.” All lickety-split edits, percussive soundscapes, deafening blasts, grunted one-liners, and searing pops of primary color, it’s an aesthetic perfectly suited to Hollywood’s oddly bland code of neo-masculinity but one that doesn’t exactly lend nuance to, well, anything. Put bluntly, this makes him both the best and worst living director to tackle “13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi,” the adaptation of Mitchell Zuckoff’s book about the six ex-military security contractors who defended two American bases in Benghazi, Libya, during the September 11, 2012, attack that killed U.S. ambassador Chris Stevens and three others.

These days, Michael Bay is best known for his seemingly endless stream of “Transformer” movies but he’s also this country’s most unabashedly pro-military director; since “Pearl Harbor” (2001), he has demonstrated an enthusiasm for artillery-laden features whose guiding principle seem to be “Keep it butch, boy.” All lickety-split edits, percussive soundscapes, deafening blasts, grunted one-liners, and searing pops of primary color, it’s an aesthetic perfectly suited to Hollywood’s oddly bland code of neo-masculinity but one that doesn’t exactly lend nuance to, well, anything. Put bluntly, this makes him both the best and worst living director to tackle “13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi,” the adaptation of Mitchell Zuckoff’s book about the six ex-military security contractors who defended two American bases in Benghazi, Libya, during the September 11, 2012, attack that killed U.S. ambassador Chris Stevens and three others.

Bay has described this as his “most real movie,” which is a queasy oxymoron even if he does achieve a grit that could be described as “social realism lite.” Reprising the strong, silent type he portrayed in last year’s “Aloha,” John Krasinski is Jack Silva (a pseudonym), the film’s anchor and a former Navy SEAL who’s been tapped as part of the CIA’s Global Response Staff (GRS) to protect U.S. intelligence agents and diplomats in dangerous areas. Together, he and the other GRS operatives comprise such a blur of white-guy bulk – big biceps, beards, and jaws – that it’s genuinely difficult to tell them apart. It doesn’t help that first-time feature screenwriter Chuck Hogan (an action star’s name if ever there were one) gives them the most cursory of character shadings: Kris “Tanto” Paronto (Pablo Schreiber) is the live wire; Dave “Boon” Benton (David Denman) is the reader; Tyrone “Rone” Woods (James Badge Dale) is the unspoken leader – you get the point. Bay’s bombast translates into a ticking off of all the items you’d put on a checklist of “Brian’s Song”-style cinematic triggers: monosyllabic in-jokes, single tears, reveals of new pregnancies, pics of infant sons, the discontinuation of a life insurance policy, flapping U.S. flags, scaffold-wrapped concrete buildings abutting glorious ruins. Boon is even reading Joseph Campbell.  The best example of the black-and-white nature of this portrayal: Silva and his cronies use the term “the bad guys” to describe pretty much any Libyan who isn’t in American thrall. Though you could argue it’s understandable given the threat they feel in the post-Gaddafi Benghazi terrain, it also underscores this film’s perilously simplistic approach.

The best example of the black-and-white nature of this portrayal: Silva and his cronies use the term “the bad guys” to describe pretty much any Libyan who isn’t in American thrall. Though you could argue it’s understandable given the threat they feel in the post-Gaddafi Benghazi terrain, it also underscores this film’s perilously simplistic approach.

In general, Libyans are depicted as generically evil presences or easily manipulated lackeys here -business as usual in what, at heart, is a classic shoot-’em-up in which martyred American males have to fight their way out of a lethal infrastructure of enemy gunfire and red tape. The red tape comes in the form of David Costabile, Hollywood’s reigning shorthand for weasel desk jockeys, who plays the CIA base chief AKA whiny bureaucrat who cock-blocks the GRS boys from protecting the bases when the attack takes place – and then takes credit for their heroics. It’s hard to imagine a narrative more tailor-made to the anti-intellectual, anti-government forces that seized upon the Benghazi attacks as a key weapon in their arsenal. (Yale and Harvard are practically curse words in the mouths of these told-you-so super troupers.)

In complete fairness, though it clocks in at 144 minutes, this film whizzes by as a visceral, impressively photographed and choreographed rescue thriller. It is also faithful to Zuckoff’s book, which is mostly constructed from interviews with the contractors. But it’s also distilled to a problematic degree. Like the operatives themselves, the film arrives at the Benghazi conflict with very little background. Sure, it takes great pains to establish that the attacks came about because the CIA, State Department, and the Pentagon were lethally disconnected from each other, but otherwise it delivers virtually no context. This means that no fingers are outright pointed at President Obama or then-Secretary of State Hilary Clinton but it also means that we are told practically  nothing of the recent history of Libya, which makes it all the easier to reduce the attackers to said bad guys. Bay’s costume designers may as well have handed out black hats to everyone but the GRS dudes.

nothing of the recent history of Libya, which makes it all the easier to reduce the attackers to said bad guys. Bay’s costume designers may as well have handed out black hats to everyone but the GRS dudes.

You could argue that it’s best to experience “13 Hours” as hyperkinetic Hollywood spectacle – sheer blood, oil, and testosterone, like a seventies exploitation flick boosted by modern movie technology. The problem is that, like the more high-minded “Zero Dark Thirty,” “13 Hours” is an agitprop that feigns neutrality. Multiplex audiences might love such films, but fashioning big-brawn, tiny-brain, lone-wolf myths out of issues as complex as U.S. involvement in the Middle East is, at this point, morally irresponsible. “I feel like I’m in a fucking horror movie,” says a soldier at one point. So do we all, brother. So do we all.

This was originally published in Word and Film.