At the risk of sounding callous, Hollywood has always clamored for sagas about mental illness, especially when they’ve been books first. “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Girl Interrupted,” “Silver Linings Playbook,” “Sybil,” “Ordinary People,” “I’m Dancing as Fast as I Can”: The list goes on and on. It’s not that all these movies are great (though I’m certainly fond of them). It’s that they possess all the key elements of a classic Hollywood weepie: Hero faces dark night of the soul; hero lives to tell the tale. But what of the hero who doesn’t live to tell the tale? Very few movies to date have told those stories, no doubt because they don’t offer the inspirational endings that fill multiplex seats.

At the risk of sounding callous, Hollywood has always clamored for sagas about mental illness, especially when they’ve been books first. “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Girl Interrupted,” “Silver Linings Playbook,” “Sybil,” “Ordinary People,” “I’m Dancing as Fast as I Can”: The list goes on and on. It’s not that all these movies are great (though I’m certainly fond of them). It’s that they possess all the key elements of a classic Hollywood weepie: Hero faces dark night of the soul; hero lives to tell the tale. But what of the hero who doesn’t live to tell the tale? Very few movies to date have told those stories, no doubt because they don’t offer the inspirational endings that fill multiplex seats.

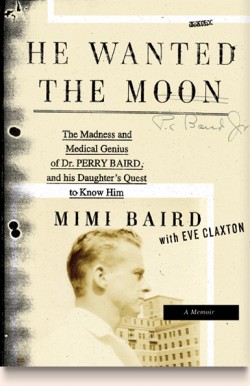

He Wanted the Moon, a 2015 double memoir to which Brad Pitt has bought the rights, is poised to be the exception to this rule. It tells the story of Dr. Perry Baird, a celebrated doctor of the 1920s and 1930s who worked to find a cure for bipolar disorder when no one really believed such a thing was possible–before bipolar disorder was even an accepted diagnosis. Baird succumbed to the disease before publishing his groundbreaking research, and was institutionalized for the rest of his life. His wife rapidly divorced him, removing him permanently from his young daughters’ lives, and he died in 1959 of a related seizure, alone, abandoned, and stripped of his medical license.

Though his name was barely mentioned while she was growing up – Mrs. Baird immediately remarried – Dr. Baird’s daughter Mimi never forgot him. After decades of searching, she found his papers, including a manuscript detailing his struggles with his disease: his mania; his catatonia; his confinements including the straitjackets, shock treatments, insulin injections, and frontal lobotomy used in his treatment; and his fruitless escapes. It’s a heartbreaker,  for sure, and He Wanted the Moon weaves this account – told in the breathless tone of a suspense thriller – with Mimi’s more factual description of her father’s life, as well as her efforts to recover his legacy.

for sure, and He Wanted the Moon weaves this account – told in the breathless tone of a suspense thriller – with Mimi’s more factual description of her father’s life, as well as her efforts to recover his legacy.

Now that Brad Pitt’s production company Plan B, responsible for such underdog narratives as “12 Years a Slave” and “Moneyball,” has bought the rights to this story, the Bairds finally may achieve the recognition they deserve. “Angels in America” scribe Tony Kushner has signed on to write the screenplay, which means it’s bound to contain all the elements that make this story so brilliantly timely: the ethics, the science, the mid-century cultural mores surrounding mental illness, and the limitations of hetero-normative family structures, especially in the intelligentsia of the U.S. Northeast. (Baird was raised in Texas, attended Harvard, and lived in the Boston area until his breakdown.)

The rest of the cast and crew has yet to be announced, but I have some ideas. James Mangold has not been working much since he helmed “Walk the Line,” easily the best music biopic of the last twenty years, and in “Girl Interrupted” he demonstrated a knack for narratives about psychiatric hospitals – as well as an ability to nail that somewhat elusive Boston vibe. (“Girl” is adapted from Susanna Kaysen’s memoir about her stint at Massachusetts’s notorious McLean Hospital.) All told, the director’s sweet, drifting melancholia – even his use of dusty sunlight – could balance Kushner’s heady rigor well. The grown Mimi could be played by the underutilized, ruefully dogged Amy Ryan, who has shown in projects as far-ranging as “The Office” and “The Wire” that she can pretty much do anything. As for Dr. Baird, it’d be too obvious to cast Peter Sarsgaard in this role – though, with his clammy, queasy passion, he’d do it wonderfully. Instead, Matt Damon should be our man. Baird is described as such a Greek god of a man – handsome, charming, athletic – that his physical and mental deterioration is all the more striking. From “The Martian,” we know Boston-born Damon can handle this sort of transformation, and his charisma – a good-guy glibness that’s always masked a shadowy complexity – seems the perfect entry into this harrowing, eminently worthy story.

As for Dr. Baird, it’d be too obvious to cast Peter Sarsgaard in this role – though, with his clammy, queasy passion, he’d do it wonderfully. Instead, Matt Damon should be our man. Baird is described as such a Greek god of a man – handsome, charming, athletic – that his physical and mental deterioration is all the more striking. From “The Martian,” we know Boston-born Damon can handle this sort of transformation, and his charisma – a good-guy glibness that’s always masked a shadowy complexity – seems the perfect entry into this harrowing, eminently worthy story.

This was originally published on Signature.