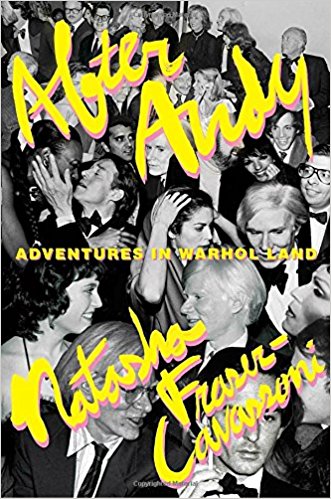

Fashion journalist Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni’s memoir, After Andy, would be a gas even if it didn’t dish on the life and times of Andy Warhol. I use the term “gas” because the whole book crackles with English, French, and American twentieth-century slang and spoonerisms in the most delightfully gassy way. To hear Fraser-Cavassoni tell it – and she’s a truth-teller even when the truth paints her as a daft bird – her whole life has been quite a gas. Born in 1963 to best-selling author Lady Antonia Frasier and politician Sir Hugh Frasier, her stepfather was Nobel Laureate winner Harold Pinter and family friends included Caroline Kennedy, Lucian Freud, and Jean Rhys. When she was seventeen, Natasha began an affair with Mick Jagger, whom she met on a luxury yacht. She also met pretty much everyone else worth meeting in seventies, eighties, and nineties London, New York, and Los Angeles during her reign as an international “it girl” who worked as a model, actress, agent, and general gadfly. In short, she was Paris Hilton before Paris Hilton, with three key exceptions. Natasha had a sense of humor. Natasha could write. And Natasha served as the last of Andy Warhol’s “English muffins” – the term for the succession of well-bred English girls who worked in the Factory, Warhol’s legendary creative studio and business center.

Fashion journalist Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni’s memoir, After Andy, would be a gas even if it didn’t dish on the life and times of Andy Warhol. I use the term “gas” because the whole book crackles with English, French, and American twentieth-century slang and spoonerisms in the most delightfully gassy way. To hear Fraser-Cavassoni tell it – and she’s a truth-teller even when the truth paints her as a daft bird – her whole life has been quite a gas. Born in 1963 to best-selling author Lady Antonia Frasier and politician Sir Hugh Frasier, her stepfather was Nobel Laureate winner Harold Pinter and family friends included Caroline Kennedy, Lucian Freud, and Jean Rhys. When she was seventeen, Natasha began an affair with Mick Jagger, whom she met on a luxury yacht. She also met pretty much everyone else worth meeting in seventies, eighties, and nineties London, New York, and Los Angeles during her reign as an international “it girl” who worked as a model, actress, agent, and general gadfly. In short, she was Paris Hilton before Paris Hilton, with three key exceptions. Natasha had a sense of humor. Natasha could write. And Natasha served as the last of Andy Warhol’s “English muffins” – the term for the succession of well-bred English girls who worked in the Factory, Warhol’s legendary creative studio and business center.

With her charisma and chutzpah, Natasha might have mixed with the beau monde even without her fancy pedigree. To her credit, though, she never pretends her varying connections didn’t serve her when she was at her least endearing. (She was quite the dilettante before settling down into writing.) Deemed one of the “new beauties of the eighties” by British Vogue, she caught Warhol’s attention at age sixteen; he tried to fix her up with an Armani model who was the son of one of his collectors. Meeting Andy again on the night of the Sean Penn-Madonna wedding (the media circus surrounding the nuptials “delighted Andy”), she made a handshake agreement to appear on his “Fifteen Minutes” program on MTV. Alas, it was not to be:  Five days later, he was dead due to complications from gallbladder surgery. But she continued to work in “Warholia” – first at Warhol Enterprises and later at the Warhol-founded magazine Interview, for whom she wrote a gossip column.

Five days later, he was dead due to complications from gallbladder surgery. But she continued to work in “Warholia” – first at Warhol Enterprises and later at the Warhol-founded magazine Interview, for whom she wrote a gossip column.

“Nata Hari,” as she calls herself, is the type to listen keenly even as she’s chatting a mile a minute, and she seems to have blathered through a nonstop series of high-profile happenings. The result is a bevy of backstage gossip about such downtown and uptown A list luminaries as painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, with whom Warhol collaborated near the end of his life, to Bridget Berlin, the Factory trustafarian known as “Bridget Polk” in the sixties, former suitor Griffin Dunne, Robert Altman, and Warren Beatty. Yes, her tales may meander, but only to include babies who never could be tossed with the bathwater. (To wit: Jerry Hall once pushed her into a bush; Vogue editor Anna Wintour is “a general of few words but much action.”) A key phrase “wear it lightly” encapsulates her refreshingly grounded relationship to fame and fortune, which always loops back to Warhol; long after his death, he still was opening all the best doors for her, especially after she moved to Paris, where he is as regarded as highly as Jerry Lewis.

There have been many great books written about Andy Warhol. Edie: American Girl, Jean Stein’s legendary oral history about Edie Sedgwick, includes vast discussions of Andy’s impact in the sixties. Holy Terror, writer and editor Bob Colacello’s memoir of his times with Andy, captures the artist in the seventies and eighties. Warhol himself captured quite a lot in the posthumously published, eternally deadpan The Andy Warhol Diaries, whose ripple effect was akin to that of Answered Prayers, his idol Truman Capote’s bridge-burner about New York high society.

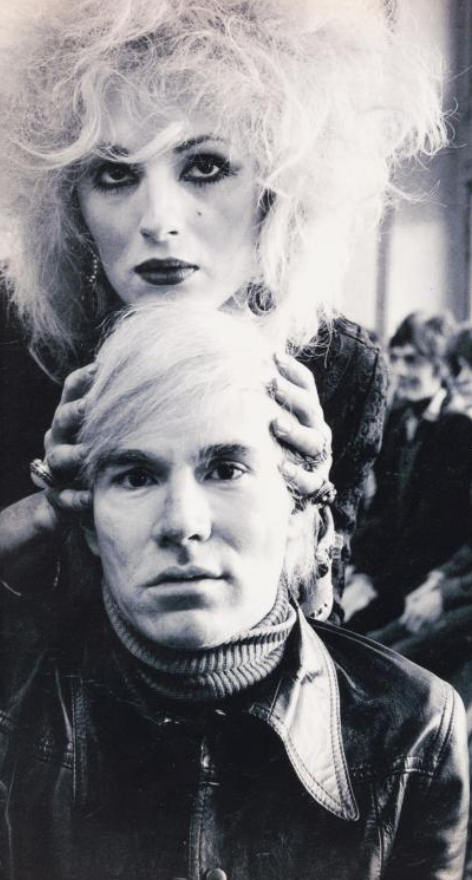

After Andy offers another useful take on the Artist – one that examines a legacy that includes enormous (and secret) antiques collection, the museum bearing his name, and an unabashed conflation of fame, business, and art. For while everyone remembers Warhol’s portraits, social connections, and signature shock of white hair, Natasha highlights what threatens to be forgotten: how he saw beauty where others saw coal in their stocking. It was through his unflagging faith in his own taste that Andy was able to curate so much mid-twentieth-century splendor –  from Edie Sedgwick and other “Warhol superstars” to the Velvet Underground, once referred to as “Andy’s band,” to the absolute splendor of a Campbell’s soup can. Indeed, as Natasha suggests, Warhol was so ahead of his time that his prescience sabotaged his artistic reputation while he was alive. The art world, she reminds us, was much smaller and rarified in the eighties, and his courtship of the public eye – not to mention his constant schilling for l.a. Eyeworks – did not endear him to key critics.

from Edie Sedgwick and other “Warhol superstars” to the Velvet Underground, once referred to as “Andy’s band,” to the absolute splendor of a Campbell’s soup can. Indeed, as Natasha suggests, Warhol was so ahead of his time that his prescience sabotaged his artistic reputation while he was alive. The art world, she reminds us, was much smaller and rarified in the eighties, and his courtship of the public eye – not to mention his constant schilling for l.a. Eyeworks – did not endear him to key critics.

Certainly the dawning of the twenty-first century – of social media, of an entire generation of “fifteen minute” celebrities, of reality TV and creative commerce – has more than vindicated the artist formerly known as Andrew Warhola. Fraser-Cavassoni cites his key advice as “try everything but try to get paid,” and she cites it fondly. I will too, now. In this gimlet-eyed memoir, Warhol emerges as a modest workhorse with fantastically immodest visions. The author writes: “He heard, saw, and understood all but in public preferred to camouflage it with a series of gees and greats.”

This was originally published at Signature.