What follows is a review adapted from a lecture I gave to the delightful Westchester and Huntington cinema clubs. It’s been a joy to share films with these groups all year.

What follows is a review adapted from a lecture I gave to the delightful Westchester and Huntington cinema clubs. It’s been a joy to share films with these groups all year.

I think this is the most beautiful film of the year. As soon as I saw it, I called [curator] David [Schwartz] and begged him to let me to show it you. And what’s most special is this beauty feels like a hard-earned decision to not just see the darkness but the lightness in a world full of oppression and corruption and hard, hard times–both then and now.

About a 15-year relationship between two musicians in Cold War-era Poland, it is directed by Pawel Pawlikowski, who in addition to directing My Summer of Love and The Woman in the Fifth, directed 2013’s Ida–so good!–which is also set in his native country of Poland. This one is based on his parents, who both died in 1989 after chasing each other for 40 years on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Like this film’s central characters, they were named Victor and Zula, and were blond and dark respectively.

So why not a straight biopic?

The director says he hates them, and I tend to agree: Trying to impose cause and effect on the messiness of real life usually results in cheesy scenes and cheesy dialogue and very reductive interpretations.

So what he does with this story instead is extraordinary. He collapses the years 1949 to 1964 into a crisp 88 minutes by cutting out any fat, any connective tissue–essentially, everything but the meat. Then, by giving us glimpses of the lovers together only every few years or so, he acquaints us with the cruel deprivations of time and distance and also with how the pleasure of the fleeting moment can free you. The overall effect is that the star-crossed aspect of their long-running affair — everything that’s miscommunicated or left unsaid — is reflected in the narrative structure itself.

Like the denatured storyline, the economy of crisp black and white and the boxy 4:3 aspect is coolly appealing too. The film begins with a handheld, documentary look–the director got his start in docs– and then, in a scene by a river early in their relationship, a wide lenses is used. The lenses become longer and the depth of field more shallow as the couple starts to feel more hemmed in by circumstances and their personal incompatibilities. And the end is signaled by a return to wide lenses, a longer depth of field and a less-glossy, less-contrasted use of the blacks and white.

Like the denatured storyline, the economy of crisp black and white and the boxy 4:3 aspect is coolly appealing too. The film begins with a handheld, documentary look–the director got his start in docs– and then, in a scene by a river early in their relationship, a wide lenses is used. The lenses become longer and the depth of field more shallow as the couple starts to feel more hemmed in by circumstances and their personal incompatibilities. And the end is signaled by a return to wide lenses, a longer depth of field and a less-glossy, less-contrasted use of the blacks and white.

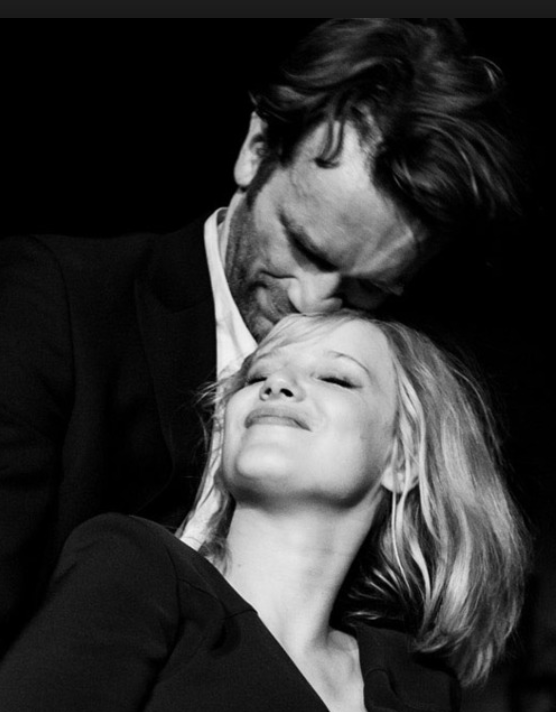

More beauty can be found in Victor and Zula’s physicality–he, played by Tomasz Kot, is dark, long, lean, brooding; she, played by Joanna Kulig, is voluptuous, pale, easily ignited, like a Cold War Amy Winehouse– and the contrast indicates their incompatibility as well as their attraction.

With her pale eyes, bee-stung lips and calculating charisma, Kulig is already a huge star in Poland and some feel is poised to a big international star. With her blowsy full figure and no-nonsense air, she’d be a breath of fresh air in Hollyood– which is exactly why I fear this will not be the case.

These two are not creatures of nuanced language and intellecutalism but artists who feel things intensely–she violently, he smolderingly–and express themselves nonverbally. Mostly, they come alive in their music, which is where all the true heat of this otherwise cool film can be found. In one of the most alive scenes, Victor is playing jazz and his country’s folk music creeps into its performance. Then there is the song “Two Hearts,” which is first introduced as a rural tune and then recycled as a haunting jazz number sung in French by Zula. All this can be attributed to the pianist and arranger Marcin Masecki, who was originally to be Wiktor and is reportedly very much like him.

Which means I want to meet him.

In a crazy way, this is the best movie musical of the year though you wouldn’t necessarily think of it that way. It’s certainly a musicologist’s dream, with the rich repertoire of rural folk music, the troupe’s Soviet-era hymns, the cool French jazz, the snatches of Bach and Gershwin–even Bill Haley & His Comets’ “Rock Around the Clock.” This is definitely a soundtrack to buy!

But all the great sex and artistic collaboration in the world can’t cover the cracks in this relationship, which is how the film splits off from the saccharine period romances to which we’re usually subjected.

Overall, these star-struck lovers are a citizens of a nation they’ve invented themselves, a nation whose constitution is fatally flawed–literally, alas. The anti-romance message might’ve been too bitter a pill, if it weren’t for the swooning musicality of the film, the transcendence of their shared passion, and the smooth editing that pares decades of suffering into 88 minutes of a rhapsody. In the end, the big question is: can love transcend personal dysfunction, history, this world?

Ultimately, this movie’s existentialism–the great pleasure it takes in the details of the moment- frees you from these despairing questions. The staccato structure lets us bask in this beautiful love–all longing looks and piano trills and torch songs and blond bangs and limbs entwined on a cobblestone streets–without getting bogged down by the geopolitical and personal suffering it causes. Miles Davis always said, “It’s not the notes you play, it’s the notes you don’t play.” That perfectly describes this film, which is as full of silences and ellipses as it is joy and melody.