“For my totem, the alley cat. All cats really want to live with me: this is one of my quiet secrets. Sensuality speaks to sensuality. We blink. They allow the slow approach of my hand and their sleek hands delight me in return. We find each other beautiful and each of us means by the hand as well as by the eye. I have my equivalent of claws and teeth, and indeed my arched back and loud hiss are my best defenses. When I need to hide my weakness, I can look fiercer than I am, but when I cannot talk or threaten or argue myself out of trouble, then I am in a lot of trouble. We survive and perish both by taking lovers. Freedom is a daily necessity like water, and we love most loyally and longest those who us at least occasionally to vanish and wander the curious night. To them we always return from the eight deaths before the last.”—Marge Piercy, Braided Lives.

“For my totem, the alley cat. All cats really want to live with me: this is one of my quiet secrets. Sensuality speaks to sensuality. We blink. They allow the slow approach of my hand and their sleek hands delight me in return. We find each other beautiful and each of us means by the hand as well as by the eye. I have my equivalent of claws and teeth, and indeed my arched back and loud hiss are my best defenses. When I need to hide my weakness, I can look fiercer than I am, but when I cannot talk or threaten or argue myself out of trouble, then I am in a lot of trouble. We survive and perish both by taking lovers. Freedom is a daily necessity like water, and we love most loyally and longest those who us at least occasionally to vanish and wander the curious night. To them we always return from the eight deaths before the last.”—Marge Piercy, Braided Lives.

When I first read this passage at age 14, I felt a surge of recognition that, even now, I only feel when I read books.

There’s an irony in that statement, since aside from the time I did LSD in 1988, this is the first time I haven’t been able to read since Iearning to do so in 1974. I’m mostly functional, but apparently functional in an economically devastating, cruelly governed pandemic does not extend to the activity that makes me feel most myself. Even harder than reading is writing anything longer than a social media posts.

So bear with me as I wander through this disenchanted forest where we all cower now. Because I am fully aware that things could be far worse–that I am lucky to have my health, a roof over my head, food in my refrigerator, a cat to cradle, even an occupation that still serves myself and others. But our problems are our problems, and when we avoid them they hold us hostage. So I am stating mine here on this day when I am not wearing a movie critic hat or an intuitive hat–no hat for anyone but me.

It’s this: I am experiencing loneliness and a loss of freedom at the same time.

Since I was small, I’ve feared losing my freedom more than I’ve feared loneliness. Isolation, I’ve always said, is a small price to pay for no one having claims upon my time or actions.

I’ve written before about how I consider myself a child of the universe, cousin to every every chirping bird, block of cement, stranger who is not really a stranger. What that means is that I prefer living where I can swing into the thick of things without having to small-talk, small-talk being the bullshit currency of shared illusions. Thus small towns or suburbs are not my bag, but I thrive in deep nature or New York City–also deep nature, though its wildlife is comprised mostly of humans in every shape, size, color. Whether living in the mermaid woods or in America’s most condensed and concentrated city, all I’ve ever had to do is open a window or go outside to be among my brethren.

Until now.

Now, no matter where I go, it’s just myself. Yes, I have community the same way everyone has community. But my not-so-secret secret is that I’m not a fan of dinner parties, book clubs, family get-togethers, one-on-one catch-ups with those people occupying the netherland between friend and acquaintance. Basically I adore communion but eschew company for company’s sake, which means I dislike most of the socialization that Zoom meetings replicate. For me it all lives under the heading of exchanges that feel more forced than fun, obligatory rather than elective. I don’t do obligations unless someone’s well-being is at stake.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m immensely grateful for all this communications technology. Without it, I wouldn’t be able to talk to my favorite people or do any of my work. But after 10 days of sheltering-in-place I realized I was far too feral for online small-talk. That for companionship I actually had to embrace my feral self.

For my totem: the alley cat.

So every sunrise I go for a sola four-mile walk. I choose that hour because I am a habitually early riser but also to move guiltlessly without a mask and so I don’t get frustrated by the non-socially distancing babyzoomers. At that hour, the streets and sidewalks are emptier than I’ve ever seen NYC at any time of day.

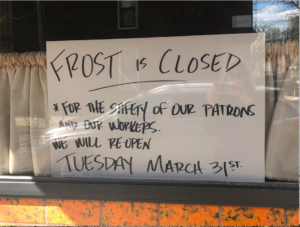

At first my body’s so thrown by the fresh air that it caves into itself; I’m like a blinking little mole. But soon enough music kicks in—I’ve made so many COVID playlists—and I start dancing past the shuttered restaurants and bars and coffee shops. Most of these small businesses will probably never reopen given how few economic supports are in place, and in them are stored so much of my personal mythology–first dates, final conversations, articles written–that I stop short for a somber moment of silence.

But out there at 6am I’m as free as I’ll be all day, so a second later gladness floods my limbs and I pirouette to Mozart, hustle to Sylvester as I imitate bird buddies’ calls.

Anyhoot-hoot! Coo coo to you.

Eventually I arrive at the East River which, for the first time since moving to this neighborhood two decades ago, I’ve truly befriended. Liberated from human pollution and lit with the magic of mid-spring, this waterfront is willing to befriend me too.

Most days the official river park is locked up because of the non-socially distancing babyzoomers. To enter it I have to scramble down rocks slick with moss and oil abutting industrial piers, then climb around the fence extending into the water so I can leap onto the the park beach.

At which point that whole park—waterfront, meadow, tulips and daffodils galore —becomes my secret garden.

Do you remember that little sickly girl in The Secret Garden? It wasn’t until until these walks inspired me to reread the book–honestly, I can only manage children’s literature right now– that I remembered she’d lost her parents to a cholera epidemic.

Pandemic mentality bubbles everywhere in our collective memory. And yet it had to rise up and stop us in our tracks before we egocentric 21st centurians (pun, yes) actively acknowledged it. We thought we were immune to everything, could control everything.

Maybe that’s why I like nature so much. It’s fundamentally untamable.

People always say we’re ruining the earth, but we’re not. We’re just ruining it for us. Look at the regions wiped by Chernobyl. Free of humans, the botany and wildlife has grown back back unsettlingly lush.

Every morning I meditate and pray at the riverfront that also is rapidly healing. Every morning the water is clearer, the air sweeter, the land less littered. Joined only by the the waves, the gulls and an occasional stray dog, a tooting steambat and the Manhattan skyline, I feel unencumbered enough to unite my good will with the good wind of the universe–of the multiverse, in fact. I pray for a collective release from disease, greed, economic and moral despair. For tools to help me be of service to everyone, even myself.

And every morning I feel exactly as I did off-season on the Outer Cape in 2017, when I was that mermaid witch tromping through sandy woods to emerge onto Ballston Beach, joined only by the dunes and the sea, the sea lions and the gulls, the salty salty big big sky.

Brooklyn, NY, and Truro, Mass: Tomato, tomawto in the COVID-19 Epidemic of 2020.

As I make my way home, the city begins to stir. People stumble by sleepily, led by their dogs as they fiddle with devices. I stop at the only coffee shop that’s open in the neighborhood most days, and the no-mask-wearing, bearded, manbunned millennial white barista is usually blasting noise music so loudly that he literally can not hear anyone speaking through their masks nor can anyone hear him.

One day, when it is my turn, I state both facts with a heavy dollop of “Where’s your mask while serving the general public?”

Not shockingly he pulls a face and says nothing. Momentarily I regret calling him out given how stressful it must be to work customer service during a pandemic. Until now I’ve only felt grateful toward essential workers–have thanked them profusely and tipped them like I’ve never tipped anyone but the poor manicurists once tasked with making my raggedy-ass cuticles and nails look grownup.

But I shake off my regret. Covid etiquette is precarious but it boils down to this: If you’re not going to act like we’re in this together, selfishness and willful ignorance will likely override the grace of this potentially unifying moment in time.

—-

And yet. Though I rarely admit it, my longing for in-person communion is what drove me back to New York from the mermaid woods in the first place.

Yes, as a wildly autonomous intuitive who registers everyone’s feelings and fetishes, traumas and timelines, I prefer to recharge by myself in my singularly occupied chambers. Yet I also embrace the fact that we humans don’t just need nature. We *are* nature, and thus have animal and mineral needs, including a very core need for intraspecial contact. For hugging, kissing, holding and being held. Even hitting and being hit once in a blue moon.

I miss other people’s smells, even the bad ones. I miss the pulse of other people’s blood. I even miss getting bumped on a NYC rush-hour subway, that wave-and-particle choreography of all of us swaying together on a traincar hurtling so many of us through dark, unknown tunnels.

Alone together. My favorite thing.

I’m open to shtupping someone new online but fear it’ll be a mocking un-intimacy. Because all day, every day, I crave touch. Not just sex but a hand upon my cheek, arm wrapped around my waist. I fall asleep imagining someone in my arms and wake with their lips brushing the nape of my neck.

I think all of us who are alone are feeling this brutal disembodiment.

All my ex-lovers who are not in relationships have emerged from the ethereal woodwork. We claim each other with a sweet, long-lost intimacy, sign everything with extra Xs, recollect how we once upon a time found each other’s flesh.

Case in point: the Legend, who lives two blocks away from me and right now is the closest neighbor I know well. He is the last person I touched before sheltering-in-place fully took root.

As we’d parted ways that day we ran into each at the coffee shop, the last day the world was remotely as we’d known it, he’d leaned in out of old, delicious habit and I’d offered my elbow instead.

Remember when knocking elbows seemed like the ultimate in social-distancing? Seven weeks ago seems like seven decades ago.

Now he comes by sometimes at the end of the afternoon–after I’ve finished readings and just as his nightcrawler self is getting going. Standing beneath my window, he hollers as we 70s kids used to holler when we wanted to hang with our pals.

“Mrs Antonellis! Can Theresa come out and play?”

When I come downstairs, we go on short, socially distanced walks, masked and gloved and sunglassed for good measure. I can’t see his facial expressions nor can he see mine so we jostle each other verbally, what we always did when we weren’t entwined in each other’s limbs or drawing blood.

The memory of all that touch is why I think he comes by. It’s the same reason I come downstairs. The voltage of our shared physical intimacy is still palpable, and palpable is what we crave–the stirring in one set of loins that could be sated by the other, the excruciating, exhilarating vulnerability of skin and blood and bone. Cock pussy mouth hand heart.

With this human I shared all that. Also tears, trauma, terrible times, but for now we don’t mention the past. Nor do we discuss the future. Instead we stroll, two aging alley cats six feet apart together in the fading sunlight of the day.

Nodding at the old-timers we separately befriended long before we met each other, shaking our heads at those treating NYC as their butler rather our shared playground. At 7pm we cheer along with our neighbors leaning out of doorframes and windowsills, tears we don’t mention dampening our masks.

Nodding at the old-timers we separately befriended long before we met each other, shaking our heads at those treating NYC as their butler rather our shared playground. At 7pm we cheer along with our neighbors leaning out of doorframes and windowsills, tears we don’t mention dampening our masks.

We mention nothing of import, nothing. But once in a while we pull down our masks and smile at each other, and I feel—

just for a second—

his touch.

Mary Oliver once wrote: “You only need to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.”

IRL has become the sweetest acronym of all.