To get to downtown Boston from suburban Newton without a car was a real pain in the mid-70s–to get anywhere from Newton without a car was a pain, really–but my father Bernie told my mother Sari that a second car was wasteful and on this point, as on so many others, he would not budge. His disdain for waste was also the reason he initially fought having the second child she was now carrying. Overpopulation was a real problem, he’d told her, and he’d stuck to that policy until he read a bunch of articles arguing for the superior adjustment of children with siblings. Then, he set about impregnating my mother with a zeal that was more clinical than impassioned. Or so she suggested to her best girlfriend Miriam later while I listened, “all big eyes and big ears,” as my mother always said when she realized she’d said something taboo in front of the kid.

To get to downtown Boston from suburban Newton without a car was a real pain in the mid-70s–to get anywhere from Newton without a car was a pain, really–but my father Bernie told my mother Sari that a second car was wasteful and on this point, as on so many others, he would not budge. His disdain for waste was also the reason he initially fought having the second child she was now carrying. Overpopulation was a real problem, he’d told her, and he’d stuck to that policy until he read a bunch of articles arguing for the superior adjustment of children with siblings. Then, he set about impregnating my mother with a zeal that was more clinical than impassioned. Or so she suggested to her best girlfriend Miriam later while I listened, “all big eyes and big ears,” as my mother always said when she realized she’d said something taboo in front of the kid.

Now every morning he zipped off to his assistant professor job in his used Toyota (so fuel-efficient he’d crowed when she’d protested its drabness), and left her high and dry with the kid and her swelling stomach.

Even on her birthday, as it turned out. This morning she’d awoke to his daily note and, of course, no car. He’d left early for work and had “fixed his own breakfast to give her a break,” as he’d written in his spidery block letters. “Happy birthday, sweetie!!” Well. The two exclamation points mollified her until she scanned the day’s list. Every day he gave her a list—go to bank, get groceries, take Lisa to park—and every day she completed it with a plodding resignation. Today she saw he’d scheduled a biannual physical for the kid.

She sighed. Though my mother grumbled, she never directly defied my father. He worked, he set the budget, he handed over a weekly allowance to cover household expenses, he expected three meals a day. Add to that he expected me to be alive and kicking when he came home from a long day of teaching and meetings. Bernie enjoyed the steady paycheck and technical research associated with his gig as a computer science instructor but deemed the rest of it, especially his students and colleagues, a drag. I was never unaware that she viewed motherhood in a similar light.

The truth was I knew my parents viewed most aspects of their new adulthood—the one they’d adopted since they’d left Allston, with its bustle of clubs and coffee shops and denizens from all walks of life–to be a drag. Lawns, neighbors, commutes: big drags. But it was if this life transition was necessitated by a larger list compiled by Bernie–Get married. Have kid. Move to the suburbs—and they’d completed these tasks with the same sense of obligation with which Sari completed the tasks Bernie assigned her every morning.

Probably any child would have felt it, not just high-strung me. But back then Sari also found a lot to appreciate in each day. Despite the imposing figure she cut, she was still the little girl who liked recess best, who fashioned small turnovers from her mom’s leftover dough, who doodled beautiful ladies in the margins of her notebooks, who admired yellow flowers poking through pavement cracks. Her domain, if you could call it that, consisted of the interstices of life, and she both relished and languished in every one she found. Her favorite moments of every week were the ones whiled away at the kitchen table of Miriam, still single and living in Allston—the two of them poking fun at the world while Sari basked in the heavenly smoke of Miriam’s cigarettes. (Bernie had made Sari quit when she got pregnant the first time.)

Probably any child would have felt it, not just high-strung me. But back then Sari also found a lot to appreciate in each day. Despite the imposing figure she cut, she was still the little girl who liked recess best, who fashioned small turnovers from her mom’s leftover dough, who doodled beautiful ladies in the margins of her notebooks, who admired yellow flowers poking through pavement cracks. Her domain, if you could call it that, consisted of the interstices of life, and she both relished and languished in every one she found. Her favorite moments of every week were the ones whiled away at the kitchen table of Miriam, still single and living in Allston—the two of them poking fun at the world while Sari basked in the heavenly smoke of Miriam’s cigarettes. (Bernie had made Sari quit when she got pregnant the first time.)

Now, with one child four months heavy in her womb and three-year-old me perched on the back of her bike, Sari cycled us down Watertown Street, the green and gold of the day flashing fast as we flew past the Italian section of our town with its appealing, jarring smells of raw garlic and pork and cheeses pouring out of all the mom and pop groceries. We pedaled past the school playground with its enormous slides and swings I couldn’t wait to one day mount, down to the Square where we caught a bus to Boston’s Downtown Crossing. As we neared the city, she began to hum at a low register. It sounded like a purr.

At the doctor’s I was pronounced a healthy child. 97 percent on the height chart–a fact sure to please five-foot-eight Bernie, who’d married six-foot-tall Sari at least partly to boost the height of his line. Only 40 percent on the weight chart: Eating already scared me.

As I chattered happily (I enjoy reading and writing! My cat is very important!), I was given two shots and one lollipop, and declared very brave and bright, two compliments I filed away to report to my daddy. (I knew my mother would not.) Dr. Kolodney might have cocked her brow at my mother’s apparent disengagement—Sari slumped against the wall, wincing at the garish colors of the pediatrician’s office, her lids lowered as if they could barely support the heavy Cleopatra lines painted upon them —but surely it was nothing a pediatrician had not seen before. Just maybe not in a Cambridge or Newton mom.

When we emerged it was midday.

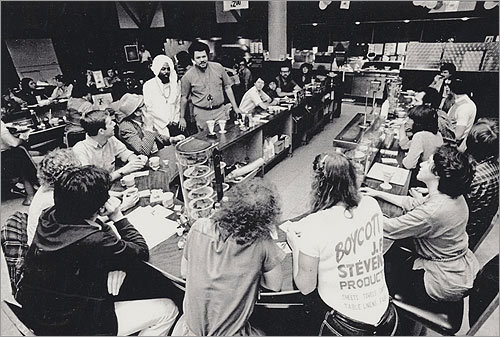

“Woolworths lunch counter,” she said, shoving the sandwiches she’d dutifully made that morning back in her big leather handbag. “It’s my birthday, and peanut butter and jelly on your birthday is for the birds.”

I’d never been to Woolworth’s before. We made our way through the first floor of the enormous five-and-dime, past the plastic flowers and boxes of crayons and construction paper and Whitman samplers to the stairs leading to the basement, where the lunch counter was located. The glamour of it all slayed me. I had so recently begun to read that words on the labels popped out at me as tantalizingly as the Crayola colors. Lozenge, Epsom, Tylenol. Jewels, all of them.

She settled me on a stool and then, when it became clear my head didn’t clear the counter, upon a booster seat that the long-faced line cook silently handed over. While we waited for menus, I looked around and she rattled through the Globe arts section that she pulled out of her purse.

She settled me on a stool and then, when it became clear my head didn’t clear the counter, upon a booster seat that the long-faced line cook silently handed over. While we waited for menus, I looked around and she rattled through the Globe arts section that she pulled out of her purse.

In those days a swath of middle-aged women—some no doubt younger than I am now—dressed like old ladies, all sticky caterpillar lashes and hot pink spots on their cheeks and plastic purple flowers festooning their hats and sensible overcoats. I ogled them sipping their milky teas and munching their greasy buns, and then swung back to regard my mother, her long legs dangling in 501s, her brown hair hanging halfway down the back of her ribbed turtleneck, her wide Sioux mouth pursed as she blew upon her eternal coffee, black and strong. My mom was pretty.

“You’re pretty,” I told her.

“Well,” she said, putting down her paper as the counterman finally handed us a menu. “Listen to you.” Ignoring his raised eyebrows, she passed it to me. She’d quickly adjusted to my being able to read and already had begun to hand over my storybooks at bedtime while she read her own book. “What do you want to eat?”

The only restaurant I’d ever visited before was McDonalds, where my mom and Miriam always bought me me a small hamburger and Coca-Cola without my having to ask, provided I not tell my father we’d gone out to eat. (He didn’t approve of the expenditure.) I’d never seen a menu before, and the options running down both sides—raspberry lime ricky, maple sundae, club sandwich, pastrami on rye, onion rings–overwhelmed me, as did the anxious buzz suddenly rising beneath the lunchroom’s clamour.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Maybe I’m not that hungry.”

“Fat chance,” she said. “I know how you work. I order something for me then you eat the whole thing.” She ordered me a grilled cheese, a hamburger for herself, and went back to her paper. I passed back the menu, and looked around some more.

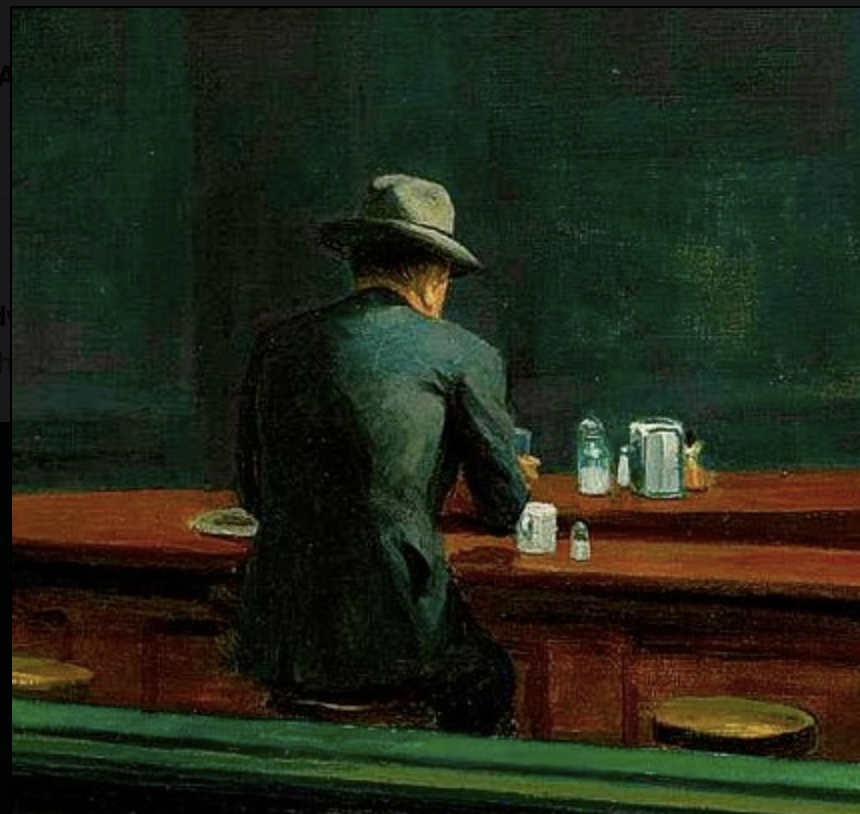

At the end of the counter sat an old man, thin and yellow. His white hair fell in shanks around his face, all brown spots and gums. With his shoulders stooped, he carefully raised his spoon from the bowl of soup he cradled, his hand shaking. Some of the soup ran down his chin onto his frayed jacket that I noticed were missing a few buttons.

“Why is that man alone?” I asked.

“Oh, you know,” my mom said without looking up. He did, though. Speaking up was something my father encouraged in his little charge, and I tended to pronounce my statements in a clear bell that Miriam and my mom mocked on their Saturday visits. Now the old man stared at me, hollow and sharp all at once. I’ve seen that look many times since: the hawkishness of those with nothing left to lose but their own shirt. But that was the first time I can remember.

I stared back and breathed fast. The daughter and wife who would no longer speak to him, the mama and daddy long dead, the small dark room with a bottle of something brown at a table and a transistor radio crackling. The odd jobs he could only sometimes do. The coins his trembling fingers could only sometimes pick up. The ocean of alonelonelyloneliness at the end and beginning of each day. The waves, yellow and thick, rising in him. The sharp sick crowding in from all sides. Trudging among people who only noticed him when they bumped into the old man walking too slow. I didn’t see it. I didn’t feel it. I was in it. He was right there inside me and I didn’t grasp it so much as was grasped.

It was too close and too much and nothing was safe and nothing was mine.

“Mama,” I said. Even at age 3 I rarely called her Mama. Sometimes I went ahead and called her Sari like my father did. She didn’t find it cute but never stopped me. Now the uncharacteristically babyish term didn’t prompt her to look up.

“Mama,” I said again. This time she sighed and snapped her paper shut. She knew what was upsetting me. I was not just my father’s child, after all. In her family such glimpses behind the veil were commonplace.

“But he’s all by himself,” I said. The old man was looking down at his soup again. I’d made him feel worse. I could feel that, too.

“Just eat your grilled cheese,” she said but tears had already ruined my sandwich and shirt.

“Oh Godfrey, Lisa,” she said. “What’re you gonna do?”

———————————–

Outside the sun burned unexpectedly bright, and the buildings and sidewalks shimmered in the mid-day heat, unusually strong for a Boston June day. “Let’s walk through the commons before we head back, shall we?” my mom said, and took my hand in her own, brown and strong. I walked on my tiptoes besides her. A fancy ballerina, almost as tall as her mother.

The wind still blew cool but as we crossed the street into the Commons we grew warmer and warmer, and soon I handed her my sweater. Two women sat cross-legged on a hill, strumming guitars together, their wide sleeves and long locks flowing in the breeze. Couples old and young walked arm in arm, and dogs ran off their leashes, squatting merrily in the grass. Even the car-honking sounded cheerful. My mother pointed out the flower beds lining the lawns, the great saturated pastels preening in the spotlight offered by the sudden summer: the violets, the peonies, the remaining lilacs.

“Just breathe,” she said and followed her own advice. “Don’t you feel like you could do anything on a day like today?”

I nodded. I had a feeling me talking would take the edge off her good mood, as it sometimes did, so I just squeezed her big, dry hand even tighter. We stopped at one of the many benches encircling the big fountains. “Take a load off,” my mom said, and lifted me up to sit beside her. Pigeons swooped around us, chortling at the good jokes they were making. I loved birds, just like my dad and grandpa did, and asked my mother if I could tear up the sandwiches in her purse for them. For a while she read her paper while I tossed out crumbs, admonishing the greediest pigeons without bothering to disguise my admiration of them. “You’re terrible,” I said joyfully, just like my mother did when my father did impressions of other faculty members.

I nodded. I had a feeling me talking would take the edge off her good mood, as it sometimes did, so I just squeezed her big, dry hand even tighter. We stopped at one of the many benches encircling the big fountains. “Take a load off,” my mom said, and lifted me up to sit beside her. Pigeons swooped around us, chortling at the good jokes they were making. I loved birds, just like my dad and grandpa did, and asked my mother if I could tear up the sandwiches in her purse for them. For a while she read her paper while I tossed out crumbs, admonishing the greediest pigeons without bothering to disguise my admiration of them. “You’re terrible,” I said joyfully, just like my mother did when my father did impressions of other faculty members.

“I’m thirsty,” I said eventually, and my mom boosted me up to the bubbler, which produced a pale-green stream that didn’t bother either of us. The cool of the water soothed the knot I was still carrying in my stomach, and after I wiped my face I leaned further back on the bench, my feet dangling halfway down while I watched some kids playing at one fountain’s edge.

Children intrigued me. The street my family lived on was actually a small highway that separated us from the rest of neighborhood. Because I spent most of my time around Bernie, Sari, and Miriam, or alone with my books and records and drawing materials, I took my verbal precociousness for granted. I only saw kids my age when one of my parents brought me down to the playground, which wasn’t that often. The result was other kids seemed halfway like dogs or cats to me. They garbled a nonsense that I couldn’t fathom, and I only understood them in the instinctive capacity that I understood the feelings of animals, trees, the lonely man at the lunch counter.

A big-limbed girl with purple barrettes that looked promisingly like candies suddenly wriggled free of her mother and jumped in the fountain, sweater and all. I watched nervously but her mom didn’t seem to mind. Soon kids followed suit while their mothers talked to each other, easy and slow.

I looked up at my mother and she shook her head. “Just what I need today,” she said. I nodded and stayed put, watching all those children muck about in the mist, the mysterious dark water pooling around their legs.

Suddenly, as if I were watching myself from far away, I leapt off the bench to join them. Once inside the spray, I could scarcely see anything but the sunshine cascading around me, rainbows in every waterdrop. I stamped in sheer exhilaration.

My mom looked up and, to my surprise, started to laugh, which emboldened me further. I jumped and splashed along with the others for what felt like hours, for once their mystifying lack of fluency not bothering me at all. Only when a cooler wind nudged a cloud in front of the sun and goose bumps formed on my arms did I climb out.

I ran back to my mother, soaked and shivering. “Oh, for Christ’s sake,” she said. “And here’s me with nothing to dry you. I’ll never hear the end of it if you catch a cold.”

I stood before her, sick with shame. We had a long way home, I knew, and I already felt clammy in a way I’d learned to dread. “I’m sorry, Mama.”

She looked at me, and in that moment I felt I was not just my father’s bright idea. Her face softened and she beamed that great, curvy smile that floored men and women alike. Lips and cheekbones, yes, but really it was those eyes, gold and grey and blue, lit up like Aladdin’s lamp, that made us all so eager to bathe in her gaze.

“Fuck it,” she said finally. “It’s my birthday.” Without another word, she led us across the Commons to Filene’s Basement, down two flights to the kids’ bins, where she pulled out a red and yellow cotton dress adorned with an interlocking lace bib.

“Do you like it?” she said, and I nodded vigorously. I’d never had a brand-new outfit before, let alone helped to pick one out. Until then it had been hand-me-down city, as my mother called it; my father saw no point in new kids clothes when my aunt handed down her three daughters’ things all the time. This dress looked exactly like the day in the park we’d just had: wonderful and unexpected. I loved it.

Sari brought it up to the register then, along with a pair of red patent-leather shoes (more beauty!) and red knee socks, and she counted out the exact change in singles and coins while the cashier tapped her foot impatiently.

On the bus home she told me, “If your father asks about the new dress, you tell him this year he bought your mother a birthday present.”