We Americans pretty much never shut up anymore. With all the technological advances of the last 20 years, there are virtually no moments left in which we have to sit and grapple with the sadness that can lurk in modern life. Only an increasingly rarified strain of cinema offers the stillness our days so sorely lack, and, at their best, such films allow us to channel ourselves with a quiet that we moviegoers crave more than we realize.

We Americans pretty much never shut up anymore. With all the technological advances of the last 20 years, there are virtually no moments left in which we have to sit and grapple with the sadness that can lurk in modern life. Only an increasingly rarified strain of cinema offers the stillness our days so sorely lack, and, at their best, such films allow us to channel ourselves with a quiet that we moviegoers crave more than we realize.

European filmmakers have always proved quite handy with quiescence; the confidence and depth it requires distinguishes such masters as Bergman, Fellini and Tati. Not surprisingly, Americans emulators have produced more varied results, as if we’re such a young nation that we’ve yet to stop fidgeting. (Woody Allen’s efforts in this area are especially awkward; his Bergman knockoffs are best forgotten.) Of today’s American directors, only Richard Linklater and Ira Sachs seem fully capable of burrowing into that cinematic silence which can yield old-soul lessons and pleasures, and I believe it’s no coincidence that their latest projects have proved the film events of the year so far. In “Boyhood,” Linklater slows us all down by making time itself his central character. Now, in “Love Is Strange,” Sachs has created a moving picture that looks and feels like a still life—a happier sort of “Scenes From a Marriage,” if that film were an enlivened oil painting featuring an older gay New York couple.

To be clear, “Love Is Strange” is an extraordinary achievement in the purest sense of the word extraordinary, for it transcends the ordinary by luxuriating in it with wonderfully oddball rhythms. It pauses at the moments in our lives that are rarely examined with any depth, and minimizes others that are typically embraced as grand occasions.

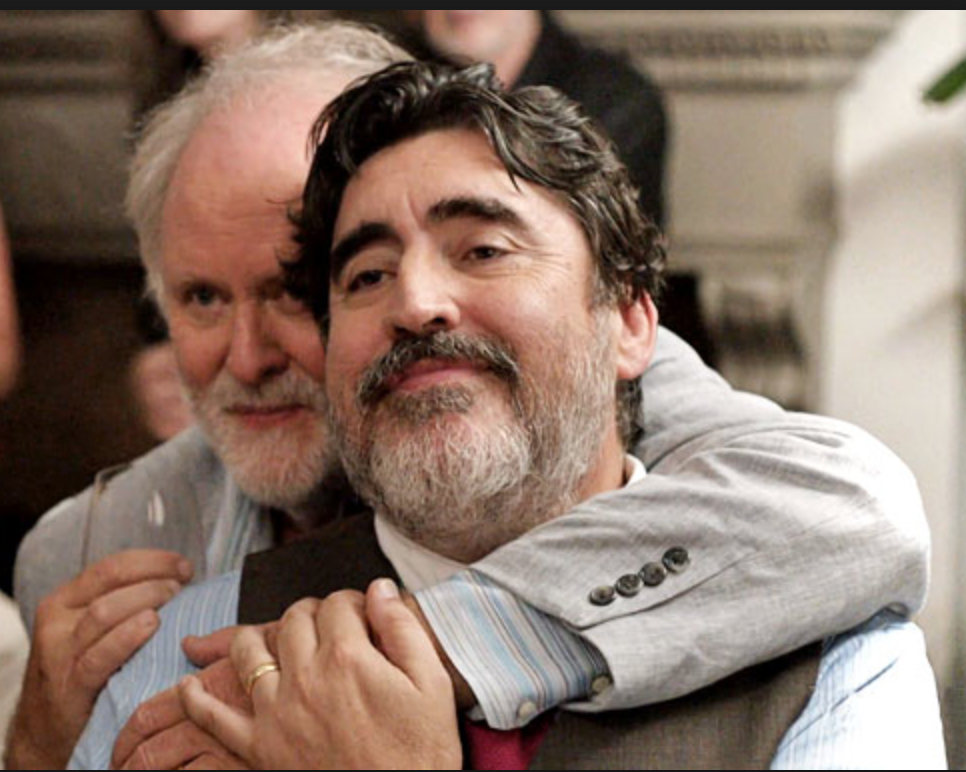

It begins, for example, with what would be the conclusion in most others: a wedding. After 39 years together, Ben (John Lithgow) and George (Alfred Molina) are taking advantage of New York’s new marriage laws and tying the knot. The ceremony itself is a quick, happy blur and then we perch along with the other attendees in Ben and George’s small, beautifully appointed living room for a party with cake, champagne, piano-playing, and the ardent testimonials that long-term love tends to inspire in others. It’s a lovely tableau.

Just as quickly, however, the story changes—and this transition elapses in front of us in a cascade that makes it difficult to gauge just how much time passes before our eyes. For though Ben and George have lived openly together for years, their official unification amounts to a betrayal of George’s contract with the Catholic school where he teaches music, and he is fired. (When his boss suggests the two pray together, George’s rebuke is mild: “I will pray by myself.”) Soon, the newly married couple can no longer afford their apartment, and, while George seeks new employment (the older Ben is well into his dotage), their friends and family step into the fold with the practical kindness that is a New York City staple. It is determined that George will live with Ted (Cheyenne Jackson) and Roberto (Manny Perez), the gay cops who live downstairs in their building, and Ben will move in with his filmmaker nephew Elliot (Darren Burrows) who lives in Brooklyn with his novelist wife Kate (the eternally, unshowily brilliant Marisa Tomei) and their unhappily bright son Joey (Charlie Tahan).

The fissures in these various platonic and romantic relationships are revealed in close quarters in a way that is never revealed in regular social congress, and Sachs does his normally skillful job of poking at the gap between our public and private selves, which only the people who love us most can tolerate. (All his films could be called “Love Is Strange.”) George’s need for quiet and solitude makes it difficult to tolerate the constant party that is Ted and Roberto’s household—he prefers Chopin to the steady drone of their video games—and Ben’s chatty warmth hardly melts the icy climes of Elliot’s homestead. Instead, Ben, a painter whose semi-success no doubt stemmed from his ability to break boundaries, reads as invasive to Kate and Elliot, who are already occupied with their largely unspoken battles about how to balance work and domestic responsibilities. The irony, of course, is that Ben must occasionally irritate quieter George as well, but rather than interrupt each others’ creative processes, the two seem to flourish together. A fascinating subtext about how the making of art—as well as art itself–fits into intimate relationships is always at hand here.

Scenes heat up leisurely and then linger, tensions widen rather than erupt, and questions arise that are never neatly answered. Nonetheless, a gist slowly, un-pedantically reveals itself: friendships become more precarious when we affect the matrices of each others’ lives. As these characters’ need for personal space becomes more desperate, we realize how contingent our own happiness is on it as well. (Really, this film is like a PSA for peace and quiet.)

When the film finally simmers to a climax, it does so gently. The stoic George breaks down when yet another party takes place at Ted and Roberto’s, and he bursts into Elliot’s household, so bereft that Kate puts the two of them together in a bunkbed for the night, sending her son to the couch. Molina and Lithgow are such tremendous actors—both are at the top of their craft right now—that they convey a not-so-tiny universe as they collapse into each other’s arms atop that tiny mattress. The comfort of their decades-old intimacy, the kind that is only truly accessed when they are together alone, underscores everything we too often forget about the rare and redemptive power of love, no matter what form it takes. (That Ben and George are gay seems less relevant than the fact that they are older, less affluent artists though the history of Stonewall and AIDS threads matter-of-factly through this narrative.)

It would make perfect sense for this film to conclude in that moment, but the ever-sly Sachs never quite lets anyone off the hook that way, including himself. Instead, he leaves us at a characteristically more forlorn and ambiguous juncture–one that poses much bigger questions about what really endures in our lives. Is it our art? Is it our love? One thing is for certain: only silence will outlive us all.

This review was originally published in Word and Film.