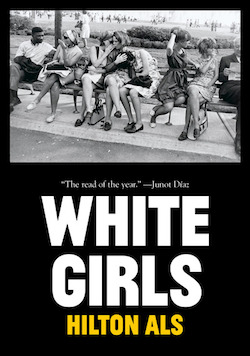

Ever since I divested myself of 90 percent of my books, I’ve been very selective about which ones I actually own. Typically these days I take them out of the library. The books that are sent to me for a gig go to Housing Works after I’m finished writing about them. But since finishing Hilton Als’ White Girls, I’ve been wanting to possess it. That is because I want it to possess me. I need to be able to hold it and write in it and embrace it as a magic talisman. What Als does in that book is treat other books, other subjects, other people as magic talismans. He weaves in and out of narrative and criticism and fiction and memoir and poetry and history to reach the heart of big ideas, and he does so with smoky, plummy eyes and smoky, plummy cardigans and smoky, plummy prose. He’s gay and far away in life (if not location) but I find myself in love with him the way I am with all souls that tender and brave-hearted. (They are rare, so rare.) He writes the way scientist-artists should, but rarely do. Edmund White does, and I like to own his books, as well. Ditto for Sherwood Anderson and Eve Babitz and Grace Paley and Marge Piercy and James Baldwin and Louisa May and Toni Morrison and E.B. White and James Joyce and Alice Walker and Pauline Kael and Leo Tolstoy and Grace Paley and Ellen Gilchrist and Adrienne Rich and, of course, Madeline L’Engle and M.F.K. Fisher.

Ever since I divested myself of 90 percent of my books, I’ve been very selective about which ones I actually own. Typically these days I take them out of the library. The books that are sent to me for a gig go to Housing Works after I’m finished writing about them. But since finishing Hilton Als’ White Girls, I’ve been wanting to possess it. That is because I want it to possess me. I need to be able to hold it and write in it and embrace it as a magic talisman. What Als does in that book is treat other books, other subjects, other people as magic talismans. He weaves in and out of narrative and criticism and fiction and memoir and poetry and history to reach the heart of big ideas, and he does so with smoky, plummy eyes and smoky, plummy cardigans and smoky, plummy prose. He’s gay and far away in life (if not location) but I find myself in love with him the way I am with all souls that tender and brave-hearted. (They are rare, so rare.) He writes the way scientist-artists should, but rarely do. Edmund White does, and I like to own his books, as well. Ditto for Sherwood Anderson and Eve Babitz and Grace Paley and Marge Piercy and James Baldwin and Louisa May and Toni Morrison and E.B. White and James Joyce and Alice Walker and Pauline Kael and Leo Tolstoy and Grace Paley and Ellen Gilchrist and Adrienne Rich and, of course, Madeline L’Engle and M.F.K. Fisher.

Sometimes when I am stuck I pull their books down from my shelves and copy out passages to channel their grace and diligence and brilliance in some small way. Sometimes I decorate the covers of their books as well. Winesburg, Ohio is featured prominently in my office with a wide stripe of glitter I applied one night when I was especially inspired.

Of course I understand how complicated the concept of “owning” is, especially when it comes to the work of a black author. But the fact remains that paying for a writer’s words is the most direct way I can honor them in our unhappily capitalistic society. (G-d knows I’m grateful when someone buys mine.) And I need to own White Girls because this fall I am seriously rolling up my sleeves to recommence my own book project.  I view a sacred item like Als’ work as a key to the gate I have trouble entering without permission. I have trouble entering it even with permission.

I view a sacred item like Als’ work as a key to the gate I have trouble entering without permission. I have trouble entering it even with permission.

I will be grateful to join in the conversation, regardless of where my words fall. I suppose I already am grateful, in some not-small way. But I would like to soar and strut and sway and spoon and shake, just like one of Als’ ladies. And for that I need his book, festooned with purple velvet and and purple feathers and purple pen, presiding over me from a special spot on my shelves that are so obviously altars.