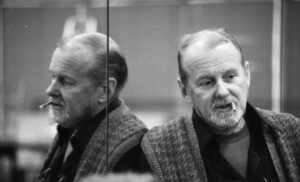

Every year as soon as daylight saving hits, I fall back into my Bob Fosse obsession. This month, in addition to mainlining his films, interviews, clips, I’m rereading Sam Wasson’s excellent Fosse biography and feeling new empathy for the dancer/choreographer/director’s struggles. Many, many people are boozers, pill poppers, cheaters, nihilists. What distinguished Fosse was the depth and charge of his creative solution to those shadows.* It’s a solution I crave.

In Fosse’s works flowed the brass tacks of vaudeville, the flourishes of the MGM musical, the liquid grace of jazz filtered through his uniquely from-the-hip economy. All of it—from the depressive cheer of “We Got the Pain” to the death drag of “All That Jazz”— paved the way for the 21st century’s “irony-is-the-new-black” ethos, eros, aesthetic. Every major icon of the last 50 years owes Fosse – from Michael Jackson to Liza to Madonna to Britney to Lady Gaga and even Beyoncé. Fashion would not be fashion without his exposed garter belts and fishnet stockings. The world is still catching up with his matter-of-fact-jack on sexuality and race.

Just look at this Little Prince (1974) scene, possibly Fosse’s last dance on film. The gloves, glasses, black ruffles, hip and neck swivels, pelvis thrusts, flexed fingers, shoulder shimmies, heel-to-toework is all so modern—so timeless, really. It’s Michael Jackson a decade later. Bojangles 50 years before. And something delightedly, self-consciously Fosse that will always charm us.

But while Bobby may have been a snake, an ouroboros he was not.  Through space and time, he continues to feed us. All autumn I’ve been seeking grace everywhere–film, faces, fashion, footwork (sadly, not fucking). Only Fosse–that ultimate F word–saves me from myself.

Through space and time, he continues to feed us. All autumn I’ve been seeking grace everywhere–film, faces, fashion, footwork (sadly, not fucking). Only Fosse–that ultimate F word–saves me from myself.

Through space and time, he continues to feed us. All autumn I’ve been seeking grace everywhere–film, faces, fashion, footwork (sadly, not fucking). Only Fosse–that ultimate F word–saves me from myself.

Through space and time, he continues to feed us. All autumn I’ve been seeking grace everywhere–film, faces, fashion, footwork (sadly, not fucking). Only Fosse–that ultimate F word–saves me from myself.—————————————-

*The downfall of most biopics is an overemphasis on the demons of seminal talents rather than their unique achievements.