This is the second and final installment of an essay that I began earlier this spring. It is a window into my book, to which I’ve been slowly returning as the world is too rapidly opening back up.

—————-

NYC has opened back up, and the smell of fresh paint suffuses every block, a top note to the concentration of garbage piling up on sidewalks, weed clouding every corner. For every person fleeing their Covid cave for fresher air and wider horizons, another is claiming a new base for big-city dreams, 16 months delayed.

NYC has opened back up, and the smell of fresh paint suffuses every block, a top note to the concentration of garbage piling up on sidewalks, weed clouding every corner. For every person fleeing their Covid cave for fresher air and wider horizons, another is claiming a new base for big-city dreams, 16 months delayed.

It all involves an awful lot of fresh paint.

Some associate this scent with toxicity—chemicals, ill health, colonization. For me, it’s a gateway to an autumn four decades ago, when Audre resurfaced and the world first opened up.

Really, it was simple. One day Audre called up, and the following Friday, without disclosing any of the long-awaited details of their conversation, my mother whisked Jennie and me into Cambridge, where Audre had rented a long apartment on a tree-lined block between Central and Inman Square. It didn’t occur to any of us to bring my father because he never strayed from his Friday routine: popcorn, tea, computer manuals, sports radio, and bed at 8:30. Of course now substitute poetry for manuals and 70s film for sports radio and my routine is not that far off, but back then his diurnal rhythms seemed the ultimate in passive domination.

———–

From the minute we stepped out of the car, a new joy flooded me–a sort of calm magic. Audre’s new place was rickety, with uneven wood floors, rusting fixtures, a long spindly corridor, and peeling paint. But the ceilings were high, the bathtub sprouted feet, and the open windows tall and wide. Best of all, the rooms were blissfully empty and bathed in sunlight. Drifting through each was seemingly the whole world. Odors from a nearby Italian bakery, Indian restaurant, West Indian storefront; the clatter of car and foot traffic and African pop and salsa and kids playing Double Dutch.

As I wandered through the apartment, freer to indulge my nosiness here than at Audre’s old house, the girls made a beeline for Jazzie’s bedroom and mysteriously shut the door. Later we would discover they’d scribbled J&J all over the walls in grand, grape-scented block letters. Shyness or overwhelm preventing them from a showier reunion, Sari and Audre immediately settled with coffee on the floor in the front room, legs tucked beneath them as they resumed their chatter as if it had never stopped.

Isaac stood in the doorway, clocking my investigations. Our height discrepancy was even greater now—I’d hit a serious growth spurt over the summer—but it only seemed to level our playing field. In the intervening months, he’d grown into himself. He seemed sturdier, with a center of gravity somehow closer to the ground. A forcefield.

Isaac stood in the doorway, clocking my investigations. Our height discrepancy was even greater now—I’d hit a serious growth spurt over the summer—but it only seemed to level our playing field. In the intervening months, he’d grown into himself. He seemed sturdier, with a center of gravity somehow closer to the ground. A forcefield.

Like Jazzy, he had long lashes and disproportionately large hands and feet for his solid, short body. I found him handsome, and worried that he knew I did.

“Are you still playing checkers?” I asked, and he smiled. “Now I play chess.”

Isaac was not easy but he was shrewd and quiet. I’d missed him more than I realized.

We wandered down to the kitchen, still full of boxes and bags, and I scrambled onto a fire escape next to the sink. On it I could see into other apartments and shared small backyards, people from all walks of life in their communal privacy, talking and eating and walking and grooving. I could even hear a turntable playing what I recognized as Otis Redding’s Dock of the Bay, a tesseract to a mysterious before-me dad perched on Boston’s Comm Ave, listening to what was then his favorite album. I breathed it all in, how gorgeously public everyone’s solitude was, how effortlessly time and space could be stacked.

Isaac climbed next to me and I registered the hot energy of his young-mannishness. Like me, he was not a very childlike child, and we were both tipping into an early puberty we might have agreed was a concept invented by grownups to diminish us had we discussed such things as hormones.

Together we watched the sun disappear behind the buildings.

I had a thousand questions but something in his stillness curtailed my chatter and so we sat silently, watching the backyard movie of all these free people, living out a dream of the 1960s that I hadn’t known had been bigger than my books. I had always liked Allston, where my godmother Miriam lived, but 1980 Cambridge with its polyglot of freaks and fanatics felt like somewhere your sharpest edges and biggest selves were barely enough in the very best of ways.

A routine developed. On Fridays my mother would leave a plate for my father’s dinner–sandwiches and chips, usually, since he considered heating things up “cooking” and doggedly Did Not Cook. Around 6 she’d pile Jen and me into the Silver Bullet, a grey 1962 Plymouth purchased from money made from decorating birthday cakes in her uniquely art deco psychedelia.

The sun already setting green and gold on the Charles, we’d drive down Memorial Drive, Jen prattling to Mom, my arm trailing out the window as I watched people picnicking, biking, strolling on the river banks.

At Audre’s we’d order something from the places downstairs. Dahl and lamb tandoori. Schezwan chicken. Once we had jerk chicken, which I loved the most. My father didn’t do hot and spicy so the rest of us didn’t.

After dinner, the girls would work on an arts and craft projects on paper, not walls, and Audre, Sari, Isaac and I would work on the home repair project du jour. It was a tradition hatched from my mother’s insistence that we help Audre paint over the girls’ purple Js.

Once we’d finished that repair, Audre had conceded that, sure, the whole apartment could stand a fresh coat, and when that was done we refinished the floors and fixtures–sanding, polishing, humming. I couldn’t get over my mother’s eager efficiency, she who could leave unwashed dishes for weeks at a time and cat litter crunching beneath your feet in the kitchen without even noticing.

I was excited about the project as well–a novelty since we were assigned no chores at home. Jen and I got no allowance so it’s not like we were indentured servants, and I’m not convinced there was even money for an allowance until my father got tenure years later. But I knew the real reason my mother never roped her children into housework. She’d have to have a system in place–an empty sink in which to wash the dishes, a discipline to enforce, and our house was so catshit-strewn, spill-sticky, flies-buzzing dirty that sometimes I felt sick as soon as I returned from school. Housework when I tried to help was like band-aids over tumors, Syssyphean.

Sari said I was a snob and since I knew this to be true, I dropped the subject. I never felt sympathy for the mess in which she found herself, and not just because we were all drowning in it. Something wilier than abject despair and patriarchy-resistance lived in her failure to clear anything out. It was the same subversion that blocked her from parenting us beyond perfunctory babysitting. A stubborn futility I deeply feared.

Even Audre would gently bring up my smart-assery. When my shticks ran too long—what Sari called my “quiz kid bullshit”–Audre would say, “How about giving the grownups some airtime, fruit loop?” But just like when she put my sister in her place, you never got the sense she was harboring darker clouds beneath her words. In fact, I’d feel redeemed–more safely contained, somehow.

I was as glad as my mother to escape to to her home.

As fall dipped into winter, her apartment slowly filled with pieces from local second-hand shops and yard sales refined by she and my mother. Gone were the tweedy couches, the dark wood and leather of her Newton house. “I let him have everything,” I heard Audre tell my mother, like she was casually offering the last egg roll. “I had zero interest in another fight with that man.”

I thrilled with her use of the phrase “that man.” To reduce a father to a mere man felt enormous somehow, a wresting of power that had never before seemed possible and immediately made me feel guilty.

Sometimes we’d come into the city early enough to prowl the streets for African masks and baskets, stained glass that dappled geometric blocks on the newly polished floors, threadbare velvet chairs and wobbly bureaus and end tables. I loved these neighborhoods so much–bustling and full of what seemed like every conversation in the world. Afterward, Audre and my mother refinished everything in strong colors that sang when you entered the room. The result was like Audre herself: vibrant, but never loud.

Some nights the mothers would shoo Isaac and I away so they could engage in adult lady talk. We’d repair to his room, less Star Wars and more bookish than his old one. We had both recently finished the Great Brain books, and had begun reading sci-fi. Asimovs I pilfered from my grandmother. Bradbury his father guiltily bought him every other weekend. He was my first friend with whom I could read side by side and I loved it. To this day, an absorbed quiet is my favorite form of intimacy.

Isaac began teaching me chess, though I always lost. I had a limited capacity for long-term strategy. Sometimes we’d play while watching Dallas on the black and white he’d swiped from their father’s office. It was the only television in the apartment and was rarely turned on. Who shot JR indeed.

“You guys don’t have a radio,” I realized one night. “Actually, I do,” he said, and pulled a transistor out from under his bed. “I use it to listen to games, but my mother says she doesn’t like it always blaring now that she’s the man of the house.”

He turned on the AM station WILD, Boston’s only Black-owned radio station, and “Rapper’s Delight” was on like it always was that year. To impress him I stood up and started imitating moves we’d seen on Soul Train the spring before. I’d memorized almost the whole song; Isaac knew it all, of course.

Well I am Wonder Mike

And I’d like to say hello

To the black to the white to the red and brown to the purple and yellow…..

Our sisters ran in the room and started dancing too, and Audre and Sari came in to see what the ruckus was about. Hot and funky, we kids danced like maniacs–crossing arms and kicking legs, spinning, doing the bump, the hustle, the Watusi, shaking our fingers in the air. Even serious Isaac was getting down. The grownups watched, eyes half closed as they leaned against the wall. “Well, okay,” said Audre finally.

This was the other difference about Audre’s new house. At my family’s, the tv was always on as well as the radio, even during dinner. Plus everybody always talking, shouting about what was in the paper, how many miles Bernie had run, what so and so had said to Sari, what song Jennie had learned in school. I blocked it all out with a book, at the kitchen table where we ate every meal and everywhere else, and went to great lengths to earn whatever wink my father threw my way.

At Audre’s such measures were unnecessary. Even my mother spoke with a greater economy and my sister rarely whined. Slowly my chatter was replaced with the bemused quiet Isaac wore so well.

Soon enough Audre started working as a nurse again. “That’s how my parents met each other,” Isaac said, and I pretended I hadn’t known. I wanted to hear what else he would say about them since he rarely brought up their marriage and, more thrillingly to me, their separation.

“She worked in the hospital where he was a resident.” The precision of his delivery suggested he’d been studying his parents’ story more than he’d let on. I nodded. Rather than pitying his plight, I envied the period on their sentence.

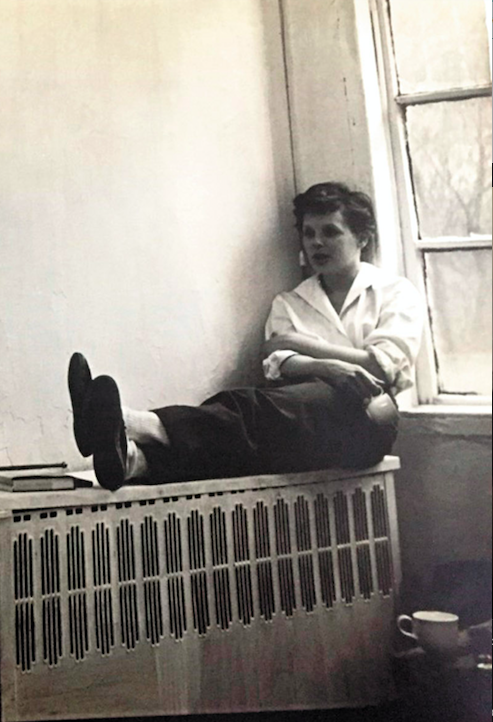

I didn’t think about kissing Isaac or even holding his hand. But I deeply admired his self-possession. More than that, I wanted to embody it, live inside it somehow. I even coveted his latchkey, which signified his independence as well as his mother’s. He seemed to have overnight achieved a burnished quality I felt unlikely to ever attain. You needed something to be liberated from, and at home I felt a baselessness that yawned as treacherously as a black hole.

One night, everyone else trooped outside to fetch dinner, but I begged off so I could finish the book I was reading. A few minutes after they left, the full extent of my solitude rushed in. I was, I knew, alone forever, lost in what I’d called the family feeling when I was younger. That sense of being nobody and nothing in the midst of others, of being unseen and unsafe, eternally unheld. I dropped my book and flattened against a wall, breathing breathing breathing in that fresh paint.

And it worked.

To this day, the smell of fresh paint, especially in the fall, fills me with a happy possibility. The sense that something broken can get fixed, that incremental work can amount to something, that anything broken can be built anew–a family without a dad, a mom who can’t TCB, a dream that just won’t die.

By the time I was twelve we didn’t go into the city much anymore; I was occupied with my preteen subterfuge and Sari was busy with that one paperback she never finished, book spine breaking as she laid it flat on her dirty kitchen table and stared out the window. The more Audre settled into her new life, the less my mother could find a foothold in it.

By the time I was twelve we didn’t go into the city much anymore; I was occupied with my preteen subterfuge and Sari was busy with that one paperback she never finished, book spine breaking as she laid it flat on her dirty kitchen table and stared out the window. The more Audre settled into her new life, the less my mother could find a foothold in it.

But that year, I listened with Adam to WILD, not top-40 WHTT as I did later with local kids whose kisses fell short of the ones he and I never shared. I dreamed city dreams–rainbow colors, stakes, stages on which to shine. Everybody burning differently, united by a ragged bravado, that dance of making it happen, captain. Consciously I didn’t know I was picking up a story my parents had put down, but I felt that pull not just out of the neighborhood but somewhere altogether fuller and finer. That city place, where even taking out the garbage had style and nothing to do with your family’s mess.

Where sweet, sweet solitude tapped into everything at once.