Lately I’ve been walking right before bed–not just a few blocks, but miles and miles.

Lately I’ve been walking right before bed–not just a few blocks, but miles and miles.

I’ve always been a big walker; everyone in my family walks a lot. Even before I moved to NYC three decades ago, I walked everywhere—-through Boston and its surrounding towns and, later, through Philadelphia and its insufferable suburbs. People I haven’t seen in twenty years will message me: I saw your parents walking down Route 16, four miles from their house. Whenever I visit my grandparents’ Northern Massachusetts town, I run into elders who say: I remember them walking everywhere together.

The difference, not to put too fine a point on it, is I walk alone.

Walking is the best way to connect with a place. More than that, it’s the best way to connect with yourself–a moving meditation that’s free and requires zero coaching.

Walking helps me notice things. People, plants, my own thoughts. Often I can’t really tell what I’m thinking until I go for a good walk. If I’m stuck as a writer or as an intuitive reader, I take the problem for a walk. Usually I return home with greater resolve.

When I lived in Cape Cod for the second half of 2017—amazing that that was five years ago—I walked at least four hours a day. On the beaches, at sunrise and sunset, and through the woods on trails Thoreau himself had charted centuries before. That was when I got bolder about walking off beaten paths, not just figuratively. In the brambles of Truro and Welfleet I learned to orient myself using the position of the sun–to sharpen my senses enough to track the closest civilization.

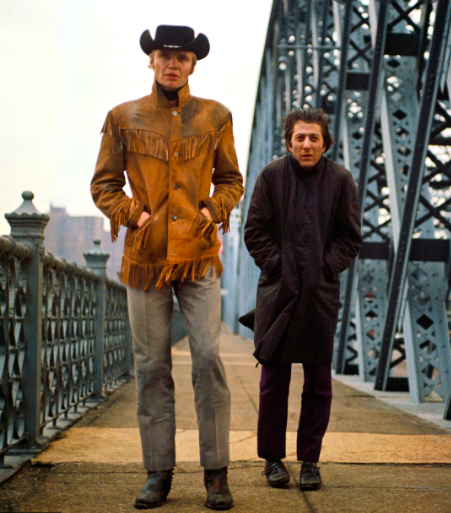

My favorite way to visit with someone has always been to go on a good walk, especially one with a destination. Nothing’s cozier than erranding with a friend–running to the butcher for her, the greenmarket for me while we figure out the world together. For years I was half in love with an Us Weekly coworker because he was willing to walk with me to Williamsburg from Midtown at the absurdly late hour our shifts ended. By now he’s blended in my memory with another tall, dark-haired drink of water I thought I fancied, but I can recall every detail of our thrilling march over the East River, our strides matched to one another’s, wind ruffling our hair, city lights unrolling beneath our feet like a red carpet announcing our arrival.

My last beau—the one I’ve been referring to as the Arsonist (previously Mr. Oyster, even more previously the love of my life)—rarely accompanied me on walks but we always had fun when he did. Everything a MGM musical as we sang and danced and swooned and spooned. The last time he really felt like my lover was an April afternoon when I lured him out of his studio for a coffee and we traipsed all over Greenpoint, the day suddenly warm and he too.

Which brings me back to my solitary evening walks. Or maybe…not just yet.

It took me a long time to view walking as a legitimate workout. For most of my life I worked out in gyms or studios, then walked for hours on city streets without validating it as additional exercise– often in heels, no less. Youth. I did yoga and pilates, danced, kick-boxed, weight-lifted, ran. And injured myself over and over. There’d always be a moment when I achieved what I viewed as perfect shape—and a next moment, when I’d rip open a tendon or throw my back or break a freaking toe. I’ve broken at least 32 bones in my body working out. (Yes, my eating disorder had something to do with that.)

Eventually, Leslie, my brilliant and patient body mechanics trainer, told me: “You know, the best exercise is just walking.”

Well, shit, I’d been doing that all along.

It took the pandemic for me to really take walking seriously, though. I couldn’t be confined to working out in my living room via Zoom and YouTube, and had long ago injured my back too badly to run. So I began tracking the exact mileage and pace of my walks, same as my father used to do for himself, my mother, and my sister. (Would have done for me had I tolerated his control.)

I stopped that mishegos as soon as it started. Walking had to be free in every sense of that word, a respite from rigor. More than that, it was high time I stopped equating self-worth with fitness levels. I gained ten pounds I’ll probably never shed, but got stronger and less accident-prone as I settled on walking at least three miles each day–three miles of fresh air and exploration and no screens. This I deemed necessary for my sanity.

Even while we were wearing masks outdoors, I slathered on lipstick before leaving the house, but now I swapped out my cute shoes for sneakers, something Leslie had been cajoling me to do for years. I made soundtracks for these journeys, just as I’d always made for working out, driving, fucking, falling in love, psyching myself up. But soon I realized there were much to be gained by simply listening to the world–to human conversations, bird calls, cricket chirps, the low thrum of the power grid keeping us afloat.

Until quarantine I’d sought nature everywhere but my own backyard, so even in those first terrifying weeks my rambles conferred new pleasures. I found a riverfront beach, smaller garden parks, pretty little floral enclaves that I never would have stumbled upon had I not made that deal with myself: three miles out of the house no matter the weather, no matter my mood.

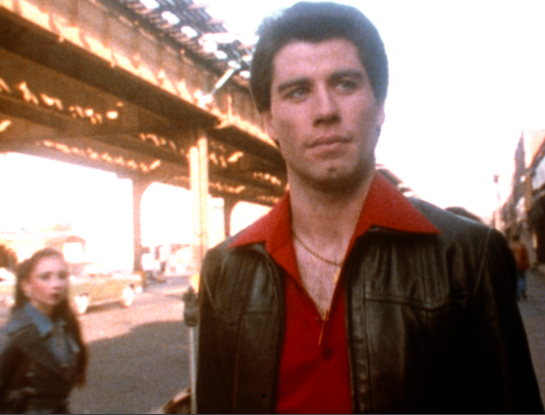

Since I was a kid I’ve been an around-the-way girl. Both my neighborhood of origin and the one where I settled as an adult are Italian-American–good groceries and charismatic men–and I’ve always befriended the older guys as well as their kids and grandkids. Most of the long-term female residents, too, though being a big Fellini blonde doesn’t endear me to every wife. Now I established that familiarity with local flora and fauna. I cultivated favorite bushes and trees and tracked their progress—buds, leaves, blooms, decay–just as I tracked neighbors’ births, weddings, illnesses, deaths. The cycle of life, plus the weather. This is what true New Yorkers clock as they rove around neighborhoods and each other.

As I rove I also clock the many changes in the neighborhood, new shrines to oat milk and natural wine as well as the countless sacrifices to grease lightening and gentrification and goddess know what else. And as I walk by the Arsonist’s big building overlooking the park or his four-story studio overlooking the river, I visit the dirty girl I’d been from the wrong side of the tracks of the town where his family resided in a posh four-story Victorian with stained glass and smart art. I try to will myself not to look in his windows but nearly always fail. Then I keep walking, and look for something else.

So I suppose I’m back to the walking alone part of this story. Because since he and I really called it a day—or, more accurately, since my Arsonist goggles were shattered once and for all —I feel the solitude of these walks more acutely than ever before. And yet I can’t bear to walk with anyone else. I’ve dropped off the face of the earth as far as many companions and colleagues are concerned because I can’t bear to make idle chitchat, can’t bear to listen mutely yet can’t bear to share my pain.

A split in your 50s has an entirely different quality than breakups when you’re younger. No one I meet now will ever know what I looked like before my waist thickened and tits and ass dropped, before I had to snip errant blond hairs from my chin and grey ones from my pussy, before I knew everyone’s tricks and didn’t have the heart to bombard them with my own.  No one I meet now will know what it was to walk with me when I turned every head on the street nor carried zero baggage but a purse.

No one I meet now will know what it was to walk with me when I turned every head on the street nor carried zero baggage but a purse.

Honestly, that may be for the better. But the thing is: I just don’t know where or even if I’ll be held again by someone I wish to hold me. I don’t know what I’m walking toward, and the bleak monotony of this fog is another good reason to keep to myself.

Still I walk because that’s what is coded in my genes and that’s what my heart needs. When I am restless, devastated, ecstatic, confused, I walk. And lately, I feel the pressure of those big emotions more intensely than ever–the pressure of embodiment itself. I’d thought my sensitivities might fade as I grew older– was even looking forward to that diminishment. But instead I register every inch of hurt and happiness, guilt and greed–mine and everyone else’s–and can dissociate from very little of this freight. My heart is open and my heart is broken.

Because now I register it all without the conviction that it carries clear-cut meaning, or at least meaning that human brains can extract. The more I professionally and personally work with the divine mystery, the more I grasp the great scope of what I don’t grasp, including the reality that my individual suffering and longing is as common as mud, not to mention that few paradoxes bear fruit. Some–most–simply exist, as ordinary and extraordinary as the sunrise.

I know I miss my man and I know he’s not my man, maybe never was. I know I miss my dad, my first walking partner, and know I wouldn’t have survived had I stayed in his sphere. I know I miss the kids I’ll never have, dreams I’ll never hatch, and know that doesn’t mean they were meant to be. I know I’m alienated and alienating and awful and alone and also as lovable as every other person I pass on the street. I know all this but that doesn’t mean I can contain it, even live with it as it wells up inside me, rising to a breaking point.

So I do my readings and reviews, keep my counsel. More and more eschew others’ company because, as I told an appalled friend the other day, “In this hallway I’m just not fit for social consumption.” I buy spring’s beautiful produce and produce beautiful spring meals.  I clean and meditate and pray and volunteer and pay bills and do all the other things that an adult person does to express care and compassion for themselves and the world at large. But still it rises—this longing, this loneliness, this massive malignant magnificent WTFery—and just as I should be finishing my day, just as I dry my last dish, brush my last tooth, send that last message, I surrender to the pull I’ve felt since I was a little girl. That whisper of the unknown, the promise and purr of something bigger than myself right outside the window.

I clean and meditate and pray and volunteer and pay bills and do all the other things that an adult person does to express care and compassion for themselves and the world at large. But still it rises—this longing, this loneliness, this massive malignant magnificent WTFery—and just as I should be finishing my day, just as I dry my last dish, brush my last tooth, send that last message, I surrender to the pull I’ve felt since I was a little girl. That whisper of the unknown, the promise and purr of something bigger than myself right outside the window.

So I strap on my sneakers and slip into a neighborhood transformed by the dark–cooler air, softer edges, everything and everyone turned inside out. I walk to tire myself out enough for sleep, to clear a landing for my dreams, to cool the desire that burns ceaselessly and now, maybe, senselessly. I walk to learn what comes next, and to release what was never mine in the first place. Mostly I walk toward the same indefinable, undetectable goalpost to which I’ve always strode. Only now I’m a ghost walking in her own footsteps. The most common magic: time, making strangers of us all.