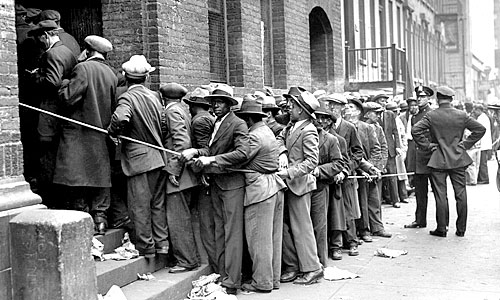

Bread line, 1932.

I live across the street from an elementary school.

Over the last 20 years, this has proven interesting for any number of reasons. When I was deciding whether I wanted children, the building loomed as a daily litmus test. Was I more charmed or irritated at the hours of 8am and 3pm, when I couldn’t walk a single step outside my door without tripping over a throng of grade schoolers? Did I find their neon-and-sparkle gear, their high-pitched cries and laughter, grating or poignant?

(From my child-free state, you may draw your own conclusion about my conclusion.)

On election days, sign-bearing advocates and impatient voters flock the block, adding an extra frisson to the air. And three-quarters of our neighborhood street parking usually is claimed by teachers—not that I’m complaining, of course. (Or I am, but don’t have a pot to piss in on this point.)

But now that school has been out of session since March, the building across the street has been repurposed as a food pantry, and most weekdays our neighborhood is colonized by long lines.

I’ve come to know the pantry’s administrators, have even helped out a bit, and what I’ve been learning about the “food-insecure” is that most of us have absolutely no idea who among us is really, really struggling. Especially now.

After three decades of living in this city, I recognize many of the pantry’s recipients, if only by face.

There are people whose struggles are visible, whether because they are mumbling the same phrase over and over or carrying their life’s possessions in garbage bags or flat-out wearing those bags. Then there are the baby-boomers with neatly pressed clothes and averted eyes, the old ladies wearing flowered house dresses and been-there-done-that jutting jaws. The green-haired punks who ride up on souped-up bikes, the hipsters sporting hemp backpacks, the young mothers with too-bright smiles and too-quiet children in strollers.

People of all ages, races, walks of life line up across the street, united only by the fact that they do not have enough food. By the fact that the other social services that should have been in place for a national disaster—the financial relief, the rent freezes, the affordable health care—are nowhere to be found.

So these people stand in downpours and in terrible heat, waiting for what by all rights should already be in their larder.

Upon returning from the Catskills last month, I realized that in my hasty departure I’d left behind my groceries. And that, for the first time in my life, I was so broke I myself might need to cross the street.

I wouldn’t have been ashamed to do it, but would have felt ridiculously guilty. That, with my excellent education and personal resources, I should not have reached that point. Which is to say: I would have felt as every other struggling American is made to feel. That my deficits stemmed from personal failures rather than public ones.

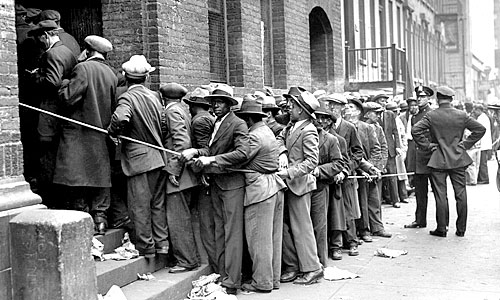

Black Panther Free Food Program recipients, 1968

Between kind donations and a new insurgence of clients, I circumvented the need for the pantry that week. But I know it’s there, and am both relieved that it is and sad that it has to be.

It’s 7:44 am as I write this, and mawing on oatmeal at my front window, I can see that across the street people are already stationing outside the pantry door. From my heart I send each and every one the hug I no longer can physically bestow.

These are not necessarily end times, but these are very hard times. The bad old days are here again, and the new dystopia is now.

Pray–and protest!–for us all.

Donate here to the NYC food bank. And if you like what you’re reading, donations are gratefully received on behalf of this blog as well.