Woman, Take Care of Thyself

When I was a little girl, I didn’t dream of my wedding and my children. I dreamed of being a writer and having my own apartment in a city, with cute clothes and an even cuter cat. In my dream, I called the cat Aces and lived in Boston but, other than that, my inner nine-year-old now crows with delight over my lifestyle.

When I was a little girl, I didn’t dream of my wedding and my children. I dreamed of being a writer and having my own apartment in a city, with cute clothes and an even cuter cat. In my dream, I called the cat Aces and lived in Boston but, other than that, my inner nine-year-old now crows with delight over my lifestyle.

The irony is that it took me a long time to be on my own even though it was all I ever wanted. In my teens, twenties, and thirties I wrangled men (biological and otherwise) into handling problems like fixing the toilet and paying bills rather than learning to handle these problems myself. For the most part, I was endearing enough to find these men but too independent to keep them. My mother called this “acting out.” I called it “not being able to sell myself out.”

But I was selling myself out anyway.

It took me a long time to recognize that I had been trained to financially objectify men, just like they’d been trained to sexually objectify me. To recognize that most women were taught the same thing, even if they’d grown up in fine, free-to-be-you-and-me households. It took me a long time to arrive at the belief that I now hold adamantly: That able human beings over the age of 18 should take care of themselves.

Keep in mind that I am 100 percent of the belief that raising children is work. But I can no longer abide people who conflate love with not having to earn their keep. Whenever anyone says—inevitably with a misty look—“he just wants to take of me,” alarm bells go off in my head. Whenever anyone says, “I just want to get married and quit working,” I feel sick. It’s not just that there’s no such thing as a free lunch. It’s that there’s no such thing as an adult who does not take care of herself. Such a concept is a bigger oxymoron than military intelligence.

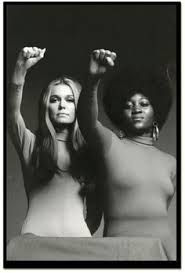

It is also disrespectful to our foremothers. They did not fight for our rights so that we could so casually squander them.  Only 150 years ago, married women were the possession of their husbands. Only a century ago, women could not vote. Only 50 years ago we did not control our own bodies. Even now women only make 77 cents on the dollar that men make, and it’s not helped by women who don’t push for fair wages since their partners really pay their way.

Only 150 years ago, married women were the possession of their husbands. Only a century ago, women could not vote. Only 50 years ago we did not control our own bodies. Even now women only make 77 cents on the dollar that men make, and it’s not helped by women who don’t push for fair wages since their partners really pay their way.

I believe in partnership, though for the most part it has not worked out for me. I believe in nurturance and appreciation and adoration and affection and even interdependence. I have friends and I have lovers, and I feel lucky about both facts. But I think this world would be a far better place if we all took care of ourselves and loved others for who they are rather than what they give us.

What Is Fixed Is Also Finite

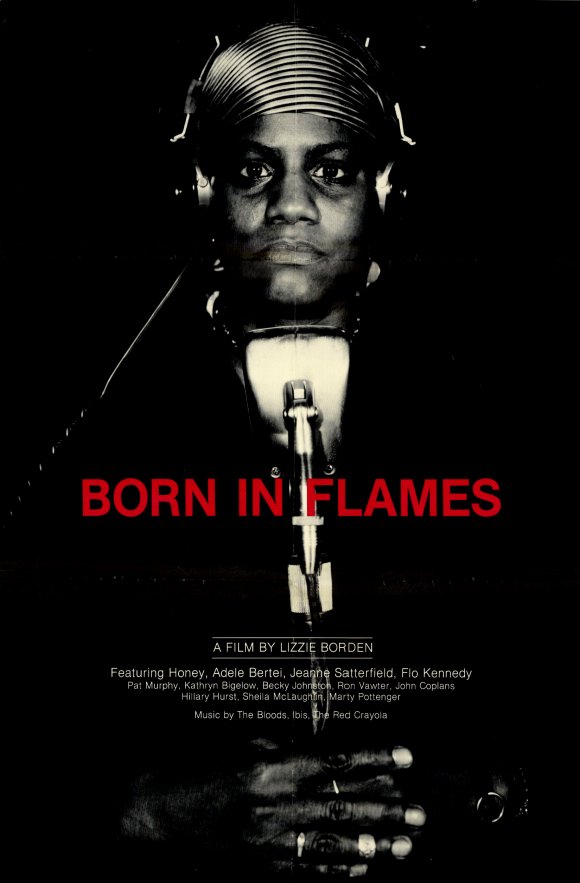

We are all prophets of this new age, and for those of us who would be safer in the sensibilities of racial separatism and martyrdom, well, if you can’t help us toward building this living church then step out of the way. Our fight will not end in terrorism and violence and it will begin in a celebration of the rights of alchemy: the transformation of shit into gold. –Lizzie Borden, “Born in Flames.”

We are all prophets of this new age, and for those of us who would be safer in the sensibilities of racial separatism and martyrdom, well, if you can’t help us toward building this living church then step out of the way. Our fight will not end in terrorism and violence and it will begin in a celebration of the rights of alchemy: the transformation of shit into gold. –Lizzie Borden, “Born in Flames.”

As a sorceress and as a critic I can tell you: This is the time of sweet, sweet change for us all. The blood moon eclipse started it, and only Hera knows where it will stop. Strap on your moon boots, pretties.

The Allegory of ‘Room’

To write about “Room,” the much-heralded adaptation of Emma Donoghue’s Man Booker Prize-nominated 2010 novel (she also penned the screenplay), is to write yourself into “Room” with nary a trap door in sight. This is not to say that the film is a black hole, though the effort to avoid spoilers is overwhelming. It’s that this story occupies a sort of fairy tale back room, where we forever are held hostage by the terror of Alice falling down the hole or of Rapunzel trapped in her tower room.

To write about “Room,” the much-heralded adaptation of Emma Donoghue’s Man Booker Prize-nominated 2010 novel (she also penned the screenplay), is to write yourself into “Room” with nary a trap door in sight. This is not to say that the film is a black hole, though the effort to avoid spoilers is overwhelming. It’s that this story occupies a sort of fairy tale back room, where we forever are held hostage by the terror of Alice falling down the hole or of Rapunzel trapped in her tower room.

The analogy of Rapunzel is more than apt, actually. “Room” is set in a 11-by-11-foot sealed, sound-proof garden shed called (of course) “Room,” in which a woman known only as Ma (Brie Larson) and her five-year-old son Jack (Jacob Tremblay) are confined. At first, we know very little. We don’t even know that Jack is a boy since he has long, long brown hair just like Ma. The two wake in the same bed, do their exercises, eat breakfast, and then pour over books together. Jack is fond of life in Room. We are introduced to his friends “lamp,” “blobby spoon,” and “rug,” and he and Ma stick to a routine in which they limit TV-watching time, take vitamins, and practice strict body and oral hygiene. But slowly we begin to grok the impossibility of their existence, especially when we realize Jack is still being breast-fed and visits “Wardrobe” every evening while an unseen man named Old Nick deactivates an alarm to enter Room and make a series of animal-like grunts. Slowly, the full horror of this situation dawns upon us: These two are prisoners, and Ma is being daily raped. Continue Reading →