I woke wanting to listen to Aretha. No big surprise there, though I haven’t been listening to my queen lately; it’s still too painful. What I really wanted to hear was new music by her, but this is no small feat when you’ve been obsessed with a now-deceased singer since you were a child.

I woke wanting to listen to Aretha. No big surprise there, though I haven’t been listening to my queen lately; it’s still too painful. What I really wanted to hear was new music by her, but this is no small feat when you’ve been obsessed with a now-deceased singer since you were a child.

It was a desire sparked by seeing Malcolm X at BAM last Saturday. It’d been so swampy that weekend, and R and I had been casting about for something to do that would diffuse the intense awkwardness of feeling like strangers after having been lovers for years and then not speaking for years after that. So it wasn’t just the prospect of seeing the Spike Lee biopic on a big screen that had dragged us three neighborhoods from our own as temperatures climbed into the 100s. We’d had to balance the prospect of sitting in pools of our drying sweat against the promise of a hefty distraction, and the latter had won.

The joint was packed, and not just because of that AC. Everyone in attendance was agog over the choreography and catharsis and craftsmanship and charisma and certitude. This was a 3.5-hour film, yet there was none of that BS chatter and smartphone-checking you find these days at a public screening. In the last 10 minutes, the late, great Ossie Davis delivered his eulogy for Malcolm, and all around me people sat silent except for the occasional nose-honking.

Over the credits sailed an Aretha recording I’d never heard before: “Someday We’ll All Be Free.”

Until the last credit R and I sat still. At the beginning of the film he’d reached for my hand and I’d been stiff, like a child afraid to disappoint a needy elder. Always sensitive to rejection, he’d dropped it after a bit and I’d forced myself not to soothe his ruffled feathers by reaching back. I’d promised myself I wouldn’t initiate any physical contact I didn’t desire. He’d done that enough for us both.

As the film progressed we’d held ourselves more and more separately, divided rather than united by the intensity of our reaction to this painful, potent film—one whose relevance, alas, was expanding every day. Ossie’s calm wisdom, Malcolm’s bold accounting, Aretha’s big voice. I wept over the elders we’d lost without anyone of their caliber taking their place, over the terrible legacy of American colonialism. R was weeping for reasons of his own—reasons I could guess at but were utterly his own.

Years before I’d blocked myself to his inner workings because comprehending them had threatened to erase my sense of self. It had taken me a long time to accept that he discerned me with a rare clarity, but mostly as something to plunder. Being mistreated by someone well-acquainted with my wounds–someone I’d believed in–is to date the worst pain I’ve experienced.

To be clear, we are all mistreated from time to time, just as we all mistreat others. It is intrinsic to this business of being alive and having needs like air and food and love and freedom. To pretend otherwise is to circumvent some of the best lessons life has to offer.

But by the time I walked away from R—or, rather, stopped chasing him down–I considered myself entirely broken. For whenever I had proved inconvenient—whenever I hadn’t kowtowed to his terms, acute sensitivities and yawning ego demands–he had made like a tree and got out of there. And when I had tried to stop him, he had turned cruel. Before we called it a day there was a miscarriage, humiliation, obfuscation, emotional and physical violence—all the damage that ensues when a girl attempts to draw blood out of a stone.

And always always money’s been central to our story.

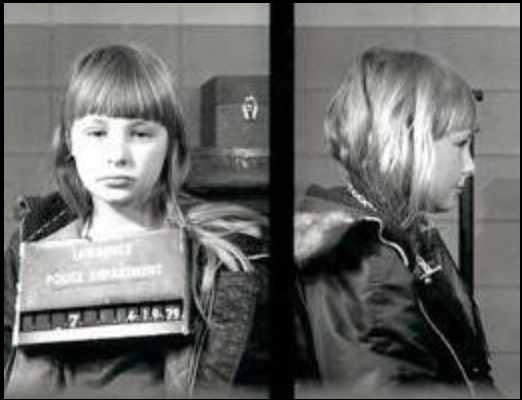

Why I stayed as long as I did has everything to do with the sort of time-travel I’ve written about before—namely, the gravitational pull of unconscious desires, of a hurt child too young to know from you-go-girl aphorisms. And I’d known R since I chronologically was that hurt child and he the hippest 11-year-old in town, rocking an MJ fro and bobbing on his toes with an extra sparkly syncopation. I’d been the friend of the daughter of his mother’s friend, a wayward waif avoiding her own home. That I was only 7 might’ve had something to do with my attraction to him. To a little girl with no brothers and a fixation on Daddy rather than Mommy, older boys represented pure manna.

But too I’d loved R’s Victorian on the right side of the tracks. (I lived on the other side of the Mass Pike.) I admired its long, spindly staircases, its many stories, the stained glass and framed prints and books and sculptures. Without being able to put it into words, I recognized its groovy, unstudied grandeur. It was the same sort of space he occupied when we were reintroduced decades later–the sort of space I’d craved as much as him when we finally got together in our 40s.

Anyway, our five years of on-and-off had been a big ole mess, and the whole time he’d had an other lady—a very rich lady my age whom I called 2E because, as in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, she was in the business of financing R’s life while draining him of any creative integrity or motivation. R is a brilliantly talented musician–always has been, always will be–and the one thing 2E and I probably have in common is a deep reverence for that sort of creative beauty. Yet she managed to distract her pretty plaything with enough pretty playthings that he lost his way.

Whereas the biggest lesson I learned from our sordid affair was to love that beauty in myself with the constancy and transparency he denied me.

So yes. Eventually I peeled away from this triangle–one in which ostensibly I was the girlfriend but it was she who financed his dreams and she with whom he shacked up in palatial splendor while I scraped to hang onto my little rent-stabilized railroad. Sometimes while working out in our neighborhood park I’d look up at their second building—yes, building—the one she’d bought them after I’d been successfully banished. On an otherwise-perfect day bile would rise before I could om-shanthi it away.

Did she know about me? Not really.

Did I know what he was doing with her? Not really.

Did he lie? All the time, to everyone, even himself. It got so I didn’t believe him when he said he was going to the deli.

Do we all lie to ourselves? Absolutely. To stop lying is to live as a fully realized being.

Understand there were wonderful things between R and me. On my angriest day I’ve never been able to deny that fact. He was fine, in a long-muscled, big-dicked, 4D-features sort of way, and our bodies dug each other. He spoke Muppet and tesseracts equally fluently, and punned better than anyone I knew–a compliment, not a complaint. Too, he possessed a gentleness I’d coveted my entire life–soft voice, eyes, touch–and like me, he understood spirit, read all the time, loved the city as a jungle of human animals and the country as a metropolis of feathers, furs, moss. Finally and maybe most importantly we shared the intoxicating shorthand of people more intent on birthing art than replicating our genes. But he always was ungrounded, disconnected in a way that privileged his feelings and observations above all others. He could be precious in a millennial way long before millennials were an official thorn in Gen X’s side.

Before I fell for him as an adult, I’d roll my eyes as he shaggy-dogged the simplest stories. After, I’d listen with the intensity of a girl seeking clues on how she might secure lifelong tenure.

After a few years of us being apart I starting canoodling with other people again, and eventually fell in love with the Legend. And though the Legend and I were an unfathomably shitty couple–wouldn’t you know he and I just now ignored each other at the coffee shop?–I learned a lot about letting go and also about how I liked to fuck. Not to put too fine a point on it, but I experienced an abandon with him that I’d never before allowed myself, and it opened up a whole new world not just in terms of who, but how, I could want.

And then a few months ago, four years after we’d stopped interacting and six months after the Legend and I were really truly done, R started nipping at the edges of my consciousness. You know, the occasional social media like–what the New York Times insists on calling orbiting. Just like always, I slipped into the rhythm he introduced, liking things back with a very careful distribution. If not exactly titillated, I was curious, as much about how I’d changed as about his agenda.

And eventually we ran into each other, and were disappointed. Him because I talked about myself too myself and made fun of him too much, the way I’ve always done when defusing a wolf I didn’t think I could otherwise escape. Me because he took liberties to which he no longer had a right. Talked dirty, ogled, pawed at me a few times. It seemed he had no interest in how I was separate from how I could accommodate his desires–that even at 48 I was just a hoochie mama to this boy from the nicer part of town.

When his mother had heard we’d gotten together as adults, she’d said, “She always seemed undomesticated.” And I had understood this was her genteel way of saying I was trash. Still, I’m not sure if I understood how thoroughly she’d dismissed me until he outright called me trash somewhere in our first year. It had been a fight in which I’d called him to the carpet about what exactly was happening in that 2E palace.

And of course I was undomesticated. My first shrink used to say I was raised by a pack of wolves, and she had not just been referring to the predatory adults in my life. She also was referring to my family’s physical havoc—that my sister and I had been the nasty kids in the neighborhood, the ones with dirty clothes and hair, the ones who smelled. The ones who couldn’t invite other kids to their house because it was just too filthy.

I had never confided in anyone that the reason I’d first opted to live by myself had been the disgust my lack of home training provoked in roommates. That I was forever breaking rules of hygiene I hadn’t known existed. But this had not meant I was trash so much as feral, a fact I’d only metabolized in the four years since I’d been with R, the same four years in which I’d learned to take good care of myself.

———

Our run-in had been, as I said, mutually unsatisfying, and yet I’d felt ashamed when he’d sent me packing that day—-politely and vaguely, as had always been his way unless I demanded clear-cut actions or responses. I’d said, “Don’t you think it’s funny to meet this way right after we started messaging?”

He’d responded, “It’s cuz I’ve been sending you sex vibes,” and it was as if he’d slapped me. It’s not that he had longed for my voice or insight or jokes or, Goddess help me, my radical empathy. It was my perpetually wet pussy he was angling for, and this pissed me and my pussy off.

Yet it was he who sent me packing, not because I’d been rude and selfish so much as because I wasn’t about to spread my legs on the expensive rug 2E no doubt had bought them. And because I still didn’t know I could leave of my own accord.

So now I suppose I need to be more honest about what I wanted from this man. Now is the time for ruthless self-accounting. For if I’ve ever been trashy, it was with him.

After years of meditating on that unfortunate term, one that’s been thrown at my clan my whole life because we’re racially mixed, economically disadvantaged, ill-kempt, I’ve decided that what “trashy” really means is “transactional.” To be trashy is to prioritize your basest needs above the welfare of others and to deliberately, consistently defy the social contract. To ignore your and others’ spiritual value. Which means that trashy humans can be found in every walk of life, while the word “trashy” is often erroneously deployed to mean “other” and, let’s face it, “poor.”

Before he and I got together, I was angling for a beautiful home and R had an ability to make things very beautiful when he wished. Demoralized by my approaching middle age, I was hoping to be admired with R’s magical specificity. And I was sick of taking care of myself. I was broke, you see, and R paid for everything when we went out and bought lavish presents to boot. I rationalized it by saying it was a trickle-down economy, since his money was really 2E’s, but that was stone-cold bullshit on my part.

For the record R was the last person I got with who paid my way, but pay my way he did. He even paid my utility bills and slipped me cold hard cash. In that way, I was behaving as the trash he and his family had declared me to be.

So I was hardly perfect in this scenario. Maybe not even likable. Certainly I didn’t give a hoot about 2E’s feelings, and unlike R I rarely BS myself about my shortcomings. I know I can be cheap, selfish, egotistical; that I make short-sighted choices about cash and can be crude and uncommunicative once someone has landed on my bad side.

And I never liked 2E. Long before we got together as a couple and for reasons I’ll never understand–probably the narcissistic desire to live at the center of a harem–R arranged for me to give her an intuition reading without letting me know who she was to him beforehand. In that context she was condescending and clueless in a way that only very rich, very sheltered people can be. To date she is one of the few clients to whom I took an instant dislike.

I’ve never taken a man from a woman I’ve liked and I’ve never stolen husbands or fathers but it took me a very long time to stop stealing men from women who threw me shade. 2E belonged to that category for sure.

I suppose I resented that she thought she could buy such a fine man. By then I was legitimately gaga for him–for his wit, charm, undeniable depth. It took me years to realize he wasn’t a prostitute so much as a pimp–pimping her out for juicy one-percenter cash and blanket adoration, me for a juicy pussetta and high-frequency mirror.

If he reads that last sentence–and chances are 50-50 he ever will–he’ll deem it as trashy as everything else about me. Certainly he’ll never consider its accuracy because to do so would rob him of his hold on whatever he has left.

——–

Before we parted ways after our run-in, R gave me a thick, conical rose quartz that looked a lot like a schlong. I probably should have refused it but accepted it with real interest, pretending not to hear him as he reminded me that his own schlong was far bigger. “I know your size preferences,” he’d said and I’d recoiled, not because it wasn’t true but because his gall was beyond the pale given how many times he’d disappeared after talking me into bed. How on earth could he think such familiarity appropriate?

Because he was outrageous, and because I’d allowed such transgressions before.

Later that night, I’d pulled out the dildo and tried to make myself cum while thinking of him. Instead images rose unbidden: him stranding me in a running car on a 90-degree day while I was on crutches and my groceries went bad in the trunk, him throwing a GPS at me while I was driving us on a highway, him dumping me and then registering the domain of lisarosman.com to build out a website without my consent, him telling me about the therapy he was doing with 2E like I’d have no feelings about him working on that relationship but not our own. His scent rose in my nostrils–not his flowery, natural cologne but the cumin rot that acccumulated when he didn’t wash for days on end.

I sighed, pulled out a dildo the Legend had left at my house, came in two seconds flat.

That should have been all the information that I needed, but apparently I am in remedial self-revelation and so spent two more days with him before arriving at the conclusion that my pussy had already drawn. A week after our initial disaster run-in, he more respectfully invited me to dinner, and like Charlie Brown with Lucy and the football, I said yes.

The dinner proved unexpectedly sweet. It was a very rainy night, and after wolfing delicious pasta, we sat with hands and limbs entwined beneath a store awning transformed into an incubation tank by the heavens opening all around us. There we talked as we’d never talked before. Not about our past–I had no interest in rehashing all that unhappiness–but about what we were looking for now. I was unusually gentle and he was unusually honest. We copped to our loneliness and fears and what we hoped to share with each other, and I suppose you could call the conversation a communion. We kissed for a while at my door as if we might, as had been proposed earlier in the evening, reinvent our wheel.

But all week my vagina, normally a veritable fountain, grew dryer and dryer, and eventually began to sting. I would have been worried except that being a witch means unheeded intuition bleeds onto the map of your body. This is true of most of us.

Thus were the events leading up to our watching Malcom X alone together in the dark.

Afterward he brought me to the Big House, what I’d always called the large building overlooking the park that 2E had bought them. It was the second building she’d bought them in our neighborhood, the first now housing the amorphous music business that had soaked up every bit of the energy he’d once channeled into actually making music.

I’d been curious about this space for years and also trepidatious. Afraid, I suppose, that I’d feel like the same dirty child who first darkened his door in the 1970s.

2E had one loft and he another in this brick cavern, which confirmed his claim that their romantic alliance had “evolved into business partners and best friends.” I never saw her space–that would have been too much–but his was in really bad shape, worse than my apartment ever got before I learned to clean up after myself. Dirty dishes and dirty surfaces and endless clutter and undraining sinks and—-well, no reason to say more.

I do not list this to be cruel, nor to crow. More to explain that I experienced the one set of emotions I never imagined R’s house would provoke in me: disgust and pity. This is one of the worst cocktails you can possibly feel about a suitor. Bad for him, too, since I’ve never been one to pity-fuck someone, though I’ve been attracted to people others have found pitiful from time to time.

Perhaps that explains what happened next, though it’s not the only reason. Stripped of the rain’s magic, we’d lacked a fluency with each other on any contemporary topic and I’d remained loathe to visit the past. Altogether I was finding him ponderous.

Say it Lisa. Say it.

I wasn’t attracted to him.

Why is that so hard to write? Because I’m more accustomed to getting rejected than doing the rejecting? Once upon a time I was considered a heartbreaker, though not of the sort that left anybody behind. More of the sort–and this is another way I was trashy–who strung men and sometimes women along while pursuing greener pastures.

If I’m being super honest, I’d considered R my karmic retribution for how badly I’d treated suitors before him. Perhaps this is why I forgot, if I’d ever known, that I had agency when it came to love and lust. My whole life, the only romantic and sexual choice I’d ever recognized had been the choice to let a person in. Some people I dated for years without ever really doing so. But once I fully cathected to a person, I assumed I’d be their slave for life.

It’s such an Abused Child thing to think.

It’s such an Abused Child thing to think.

So as R showed me around his dumptruck of a place–huge but pathologically disordered–I felt his shame and insecurity and it hurt me. Honest to goodness, I would have preferred he remain the perpetrator rather than feel this weak and impotent. Even as I type this, I do not view my empathy to be codependence. I se it as a residual of the merciful joy we fleetingly shared.

When I die the days we first spent as a couple may be what flash before my eyes. To date they are some of the few instances I felt truly loved and seen by someone about whom I absolutely felt the same. Yet as long as we’re alive the story continues, doesn’t it? This is why films based on people’s real lives are invariably disappointing. The arc of human life is redundant and messy–a shaggy, shaggy dog.

But beautiful when you’re in it.

—-

Anyway, as he struggled to produce a clean glass of water we were both magnificently uncomfortable.

All day he’d been pawing at me again, complimenting my appearance, interrupting me in a way that indicated he wasn’t listening except to assess whether his moves were landing. It occurred to me that, despite another promise I’d made myself, I was deluging him with unsolicited information about myself since he had not asked one question about me, only told me about himself while admiring my physical presence.

Once upon a time such wolfishness had worked, but no more. So I’d been edging away from him, flinching before some long-ago conditioning could suppress my distaste. It scared me that I couldn’t maintain what some part of me still viewed as “dating etiquette”; the 16-year-old runaway I carried was panicking that I wouldn’t be safe if I could no longer fake the funk. Which is sad, when you think about it, because a person has a right to respond any which way to uninvited physical contact. Except that if you’re a lamb in wolf’s clothing dealing with a wolf in lamb’s clothing, the boundaries grow super—well, super furry.

Maybe to avoid that platform bed looming accusingly in the center of his bachelor pad, he offered to show me his roof garden. I think that’s when my annoyance began to push to the surface. He actually said something like, “Isn’t it nice to look down on the whole neighborhood?”

And I didn’t say anything. Instead I pulled out my phone and asked if I could read something to him. It was a post I’d written about my grandfather and great-grandmother and loneliness in a crowd. Ostensibly I wanted to read it to R because there were relevant passages about connecting to people from a distance rather than up close, which is a quality he and I share.

But there was more to it, even if I didn’t acknowledge this at the time. I’d sensed he would react badly to anything about my family, and some part of me must have required that information. It’s just when you’re denying your intuition so strongly that your body is manufacturing physical symptoms to get through to you, you’re operating under the danger that your unconscious may seize the wheel completely.

So after showing him a photo of my grandfather Nathaniel with my great grandmother Rubenfire, I began to read the piece. And he stopped me immediately.

He was upset that I was talking about Rubenfire in his house, he said, and that I had showed him an image of her. He had felt victimized by my grandfather’s mother, it turned out.

This assertion made me apoplectic, and not just because he’d never have stood for it if I’d interrupted while he was sharing one of his compositions.

On the first weekend that we had gotten together—the weekend he officially ended it with 2E so he could be with me—my eldest goddaughter K and I had visited his family’s estate. They’d moved from our hometown to a posher region of Massachusetts, and as it was his birthday weekend and I’d been in town for Memorial Day Weekend anyway, I’d dropped by on his invitation. We’d feasted on wine and fruit salad while his mother had fixed me with that same, unfriendly regard she’d fixed on me years before. Afterward we’d all gone for what R later called the Godfather Walk–a reference to the stroll Michael Coreleone takes with Apollonia while her entire family trails behind them from a supervisory distance. There was a heavy pull in my pelvis, a rising awareness of his mouth, skin (soul). The urge to lean against him, to hook my arm into his, was powerful.

Everyone present felt the glow between us.

As the sun began to drop my goddaughter and I left to visit Rubenfire’s grave for a ritual I had back then–a way of honoring the hard work, resourcefulness and sacrifices that had ensured her family’s survival. Which is to say, she’d been a prostitute and it had cost her.

On every graveside visit, I’d chat with Rubenfire before pouring out the booze she liked best. I’d thank her, catch her up like she was a living family member, and request her guidance in landing better gigs, making better connections, tackling obstacles–essentially in upholding our line. Afterward I’d experience good wind on my back, whether because she’d exerted her influence from the other side or because I’d sharpened my intent by naming it aloud.

This time I asked her to bring R and me together if the divine intelligence of the universe deemed it best.

That night the light fixture above my bed suddenly fell down, and K, R, and R’s sister reported being pulled out of their slumber by a presence they could not describe but could definitely sense. And the next morning, as R and I shared notes on what had occurred, I finally expressed my desire for him.

For months—years—he had been expressing his passion for me and I’d been fending off his advances since I was unwilling to serve as his side piece when 2E was on the other coast. Now I told him in no uncertain terms that of course I desired and adored him–that by then he was all I could think of–and that if he made himself genuinely available I would avail myself in turn.

For months—years—he had been expressing his passion for me and I’d been fending off his advances since I was unwilling to serve as his side piece when 2E was on the other coast. Now I told him in no uncertain terms that of course I desired and adored him–that by then he was all I could think of–and that if he made himself genuinely available I would avail myself in turn.

And so he leapt onto a plane and into our future. Flew across the country to end it with 2E, and then into my bed from which we did not emerge for three days.

I tell you we fucked so much I lost my ability to walk.

And for a few months after that—maybe only a few weeks—we lived in heaven. And then real life crashed through and I remembered the old joke–What do you call a musician without a girlfriend? Homeless!–and 2E and he began the process of getting what they both wanted. Really I had no chance though I didn’t realize that until years later. My most dangerous naivete has always been the assumption I could never be naïve.

God knows I was imperfect in other ways, too. It’ll never be a coincidence that I was as broke then as I am now.

So bad.

——–

So there we were last Saturday on the roof of the second place 2E bought him, the one I’d never visited since the purchase took place once I was safely out of the picture, and there he was chastising me for ushering Rubenfire’s energy into his home.

She had visited him at his parent’s home two years after that original visitiation, he said, annoyed that I did not remember.

He went on to say in the same injured tone that Rubenfire had arrived at his parents’ home while he was visiting–that she had shaken ceilings, slammed doors, messed with the light. That she had scared his niece and nephew.

And this is when I lost my temper, though I didn’t blow my lid as I had in the past.

Even I, a psychic, could not believe he was laying this event at my feet as if it were an indisputable fact. As if it were 100 percent true that my great grandmother had caused that disturbance—not some other set of circumstances or some other entity.

When I said this to him, he replied that he knew it was her because she was the only entity he had ever invited into his space. “Don’t you remember?” he said, and I could hear that familiar sanctimony creep into his voice. “I took vodka from my brother-in-law that I later had to replace so you could bring it to her grave?” I shook my head, thinking why would I remember this when I’ve been so busy trying to forget all the other shit you laid at my door?

Then I wondered anew why I was there, looking down at my beloved park from his Grand-Poobah perspective, and said pretty much the same thing aloud.

“I can’t believe you would bring a picture of her into my house,” he said. “She scared children,” he said again, as if it were his ultimate ace in the hole. Who could dispute the welfare of children?

I felt like laughing and also screaming. He was acting like it had been the Amityville Horror. Yet, in all the time I’d consulted my great-grandmother’s spirit—and years ago I’d let her rest so I could pursue adulthood on my own terms—I’d never known her to achieve that level of uninvited disturbance. And even if she had–

“I find it amazing you’re putting this on me and her,” I said. “That you don’t have the good grace to acknowledge that on the very off chance she actually did rock your house, she may have been responding to the fact that you strung me along for years.”

He recoiled, and said even more prissily that our relationship was a separate issue, and that if I wanted to discuss our past, we could do so another time, as we also could discuss his feelings about my practice.

You should have heard the audible quotation marks he placed around “practice.”

I saw he’d never take responsibility for his treatment of me, that he’d always warp the facts so he was a victim of me and my whore grandmother’s nasty pussy power, our unregulated voltage. I saw that this was probably the line he’d fed 2E so they could glide into a well-appointed sunset together. That to him I’d hardly been more than a red-lipsticked clarification device.

I saw that it didn’t matter anymore.

That even as he lived in a cesspool financed by this hapless rich lady he would unapologetically, unreflectively act like it was me and my line who were the the bad seeds, the child-molesters, the trash, while he and his family’s fahts smelled like roses–floated far above the madding park, as it it were.

The only way to prove him wrong would be to disengage quietly and completely. So I did something I have never done before, not with him, not with any other lover. I said goodbye, and left.

The only way to prove him wrong would be to disengage quietly and completely. So I did something I have never done before, not with him, not with any other lover. I said goodbye, and left.

As I descended his stairwell, I became very frightened. I understood I was changing my life in real time and paused. What if I left my keys there? Would I dare go back? More to the point, would I dare leave again if I did? With shaking hands I rifled through my bag while he stood silently behind me. Then my fingers connected with that reassuring metal, and I muttered thank you and opened the door. Now street-level, I said thank you again, and walked alone toward rooms of my own.

I couldn’t figure out why I was thanking him, but I meant it.

Really, I could just as easily have said sorry. For the ways I’d used him too—not only for his all-seeing gaze but for those many metaphorical free lunches, for the drama in which I’d participated to postpone tackling the creative and financial obstacles impeding me today.

But thanking him felt right. I was grateful for the window in which he’d gotten past himself to honor our connection, ten years ago and then again in this last week. I was grateful for the lessons I’d learned from his presence and absence, his generosity and parsimony.

I had told him I loved him on that rainy night, and knew as I marched across the park that this would always be true. But it was also true that I no longer desired him—that our dance had ended, at least for now, and that this was perhaps the saddest and most frustrating fact of them all.

——

I had never stopped wanting R, not even after amassing incontrovertible evidence that he wouldn’t come correct. I had not stopped wanting him even after I knew, as he’d demonstrated again, that he viewed himself as a delicate flower whose ecosystem was woefully endangered by my rough-trade Rosmania.

I had never stopped feeling like that sexy trashy girl who deserved to be toyed and trifled with, fucked and discarded, sidelined and backdoored. He had never stopped treated me like her, either.

I’d figured I’d stop letting him treat me that way, but I’d never figured there’d come a time when I didn’t find his reduction masquerading as seduction appealing.

I felt free, and frightened by that freedom. Because not caring enough to stay and fight—feeling drained of all that desire—did not register as a triumph so much as a roaring emptiness. A terrible lack of faith there’d ever be anything and anybody else.

Then I walked into the remains of the day, and smiled. Because once again my great-grandmother had moved me forward.

Then I walked into the remains of the day, and smiled. Because once again my great-grandmother had moved me forward.

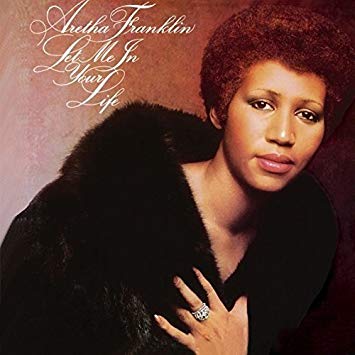

And when I woke today, I found an Aretha album I’d never heard before–Let Me In Your Life, if you can believe them apples. I listened as I lay on my clean rug, and listed all the debts I had to pay, fears I had to tackle, apologies I had to make. All the finish lines I had to cross to fully enter a new stage of life. Finally I felt quiet and cool enough to send R love.

So long as we remain open and self-reckoning, there’s always a new track to be found.