When I first came to Truro, it was only to be for a month. I had put the word out among my extended circle that I was looking to live in rural New England in September, and had rolled my eyes as I’d done so. Who’d be willing to lend me their empty house wily-nily for four weeks?

When I first came to Truro, it was only to be for a month. I had put the word out among my extended circle that I was looking to live in rural New England in September, and had rolled my eyes as I’d done so. Who’d be willing to lend me their empty house wily-nily for four weeks?

I had gall.

But as is often the case when change is necessary, that gall paid off. A friend from high school—someone I liked but had never known well—got in touch through Facebook, and next thing I knew Grace and I were hurtling to Truro in a car full of cat food, thin cotton dresses, and platform shoes.

That’s who I was on September 7. Tired eyes, disappointed smiles, trailing glamour like yesterday’s big idea. Grief-stricken about the hateful ignorance validated by the Trussian Oligarchy. Grief-stricken about who I no longer was.

I had no idea of what to expect as I drove away from Brooklyn, and neither did Katie, my high school acquaintance who had just availed me of her family summer home. I could have been a mistress of the darkest arts, set to plunder her clan’s precious resources. She could have been luring me into the real-life version of a very bad horror film. Instead, I walked into her safe haven in the woods, held by her generous good wishes and the most glorious beaches on the Northeast Corridor. And we entered into a friendship that has shown us all kinds of new horizons.

My goals, as I stated them to Katie, were threefold: to write 30,000 words of this story I wasn’t sure I could tell. To put a period on my runon sentence of a dalliance with a Williamsburg manic pixie dreamboy. And to “get back in my body,” a phrase that felt embarrassingly vague even as I uttered it.

I thought I meant “drop some weight.” Now I realize I meant: reenter the cycle of life. This I did.

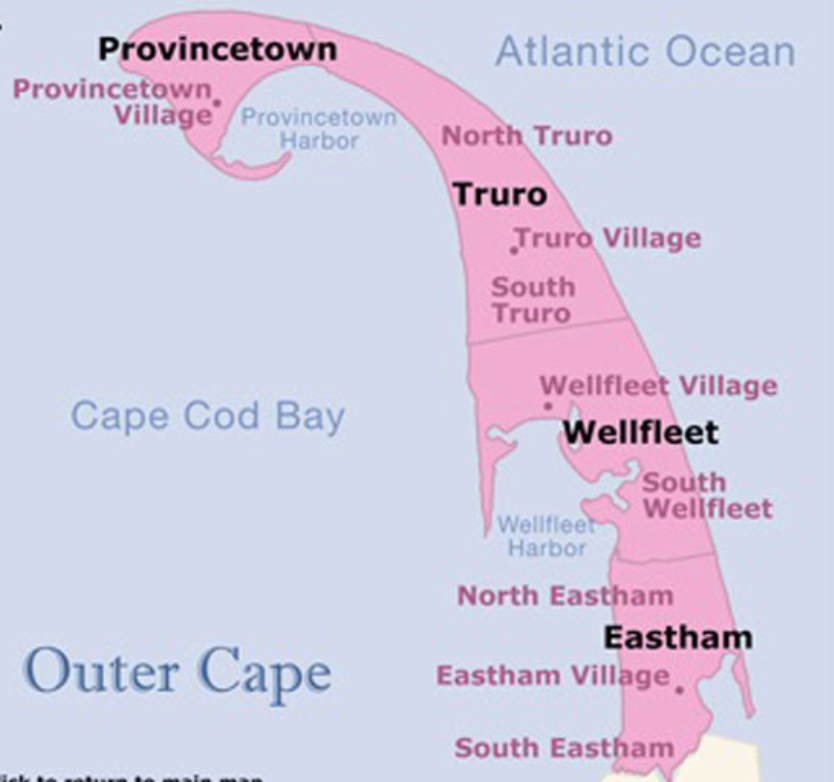

The first few weeks were splendid but terrifying. I’ve lived alone for most of my adult life, but alone on the Outer Cape off-season is a different level of solitude. It’s not just that I had to adjust to nature’s scope, to the reality that if I disappeared on a hike it might take days for anyone to notice. I also had to adjust to the volume of my thoughts untempered by the buzz of a million other human frequencies.

At first I just flitted around like a kid set loose in a candy shop. The house was lovely and well-appointed, with many large windows and a huge kitchen. The environs themselves were gorgeously varied—-woods, farmland, bogs, beaches I introduced myself to the spirits of the land, and watched as permakitten Grace did the same. I might have feared things that went bump in the night, but she instantly befriended them, racing around in the wee hours with a glee that cracked me up even as I wondered who she was meeting.

At first I just flitted around like a kid set loose in a candy shop. The house was lovely and well-appointed, with many large windows and a huge kitchen. The environs themselves were gorgeously varied—-woods, farmland, bogs, beaches I introduced myself to the spirits of the land, and watched as permakitten Grace did the same. I might have feared things that went bump in the night, but she instantly befriended them, racing around in the wee hours with a glee that cracked me up even as I wondered who she was meeting.

In September, many tourist staples remain open on the Outer Cape, and friends came up from Boston to sit on beaches and porches with me. I ate lobster rolls, went to harvest festivals, read books in the sun. In between all that heaven I faced my demons.

I’d cleared out my work schedule—not hard given how little outside employment I’ve had as this year has progressed—and set up a writing schedule instead. Get up at 5, write at least 700 words, hike in the afternoon.

It was idyllic, but not easy. I’ve wanted to write this book my whole life, but feared it wouldn’t find a home. More than that, I have feared exposure—not just to others, but to myself. I harbor a deep well of rage and sorrow no matter how much therapy I do. I feared unveiling it would tear me apart. I feared unveiling it would tear others apart.

But for a very long time this bildungsrosman has quietly held me hostage, and I’ve known one day I would write it, even if it meant unleashing my worst beasts along with it. That this darkness was necessary if I wished to excavate its power.

So after every other avenue in my life dried up, I finally began writing into this disenchanted forest.

At first, I wrote breezily—the cutesie family myths, essentially–and walked at most a mile on clearly delineated paths. But slowly this land worked its magic on me, and I deepened roots. I rose and slept with the sun, followed tidal and lunar paths. Tapped into bloodlines and wept often, danced too. I stopped Netflixing and started really listening to music for the first time in years, letting the shuffle gods decide what I should hear. Slim Harpo for when my father’s love of the blues informed my own. Kate Bush and her lilting underworld magic. Princie, Joni, Jill Scott, Stevie Wonder, Miles Davis, Erykah Badu. And Aretha, always Aretha–she who has raised me without meeting me once.

It seems no mistake that Katie’s deceased father was a composer of significant repute, for I felt his unruly creativity everywhere as music spilled through the house’s speakers. Onto the patio as I wrote in the morning. Into the back yard as the days’ shadows grew longer. He tapped his foot when I malingered, beamed me good will when I clicked into a flow.

It seems no mistake that Katie’s deceased father was a composer of significant repute, for I felt his unruly creativity everywhere as music spilled through the house’s speakers. Onto the patio as I wrote in the morning. Into the back yard as the days’ shadows grew longer. He tapped his foot when I malingered, beamed me good will when I clicked into a flow.

For as my time here lengthened–as I steeled my nerve and asked if one month could slip into two (and then…)–so did my writing sessions. At first, I had to set an alarm to sit with these stories for even 30 minutes at a time. But as this land held me closer, some days I didn’t dare stop working for hours at a time. I still didn’t know if anyone else would want to read this story but after a few weeks I knew I would. And that I had no business getting in its way as it poured through my fingers.

It’s no coincidence that my hikes grew more baroque as I dove deeper into my work. I found more out-of-the-way trails and dared to walk onto paths less clearly marked. All around me thrived a wilderness matching my own, and I thrilled at the bounty of its ordinary-extraordinary beauty. The lavender and yellow buds and bright green hillsgave way to fall’s oranges and golds, its denatured grasses, and I drank it all in. The hidden ponds. The heathered moors. The birch forests. The enchanted cottages.

I walked in Hurricane Jose. I walked on very hot days. I walked as the sun beat hastier retreats. I walked even when I felt cynical and stuck.

Especially then.

Something else happened as I delved into all that wilderness. I found allies. In the mornings, Katie and I would discuss our daily goals, and in the evenings would compare notes on our progress. It’s no coincidence she calls her coaching practice Modern Pilgrim, for she proved an ideal co-conspirator as I trekked where I’d not trekked before. We saw how her work and mine complemented each other, and began to make plans. One day she suggested I tell her when I went out on my hikes so she could ensure my return. Amazed I’d never thought of this, I felt emboldened to go further and further afield.

There in the middle of a glorious nowhere, I finally felt seen.

From Boston, Melina checked in regularly in her typical unassuming fashion. Her care packages, complete with soft warm socks and letters from my goddaughters, made me cry grateful tears. Rachel checked in most mornings, bathing me with the warmth she offers even when I’m at my prickliest, and I drank coffee from a big cup she thoughtfully provided. Others reached out, and from this place where I’d been laid open, I was able to shine them less qualified love and compassion. My friendships bloomed.

Modern Pilgrim surveying all she’s shared with me.

Soon, even on days when I did not tell people I was out on a hike, I felt their support and guidance. It shored me as I wrote into the hardest parts of my story as well. The prose deepened and, yes, darkened, and the path of my story began to reveal its entirety. Every day I sent pages to Beztie and every day she received them with her clear heart and wit. On days I was stuck she cheered me on no matter how bratty she found me.

Temperatures continued to drop, and on rainy days I prowled for a cold-weather wardrobe in thrift shops, not just to find bargains but to embrace the past of the region. The salty, sweet older women volunteering at these good-cause shops; the stories living in these velvet dresses, Harris tweed overcoats, hopeful berets: they all sparked my imagination like an attic I didn’t know I had. From Meg, I snagged a pair of silver wide-legged pants and a copper pleather skirt and then it was official: I’d morphed into the space crone of my dreams: swashbuckling, briney, otherworldly. A human time machine.

One morning, Katie and I were texting and she wrote “forest and foremost,” meaning “first and foremost.” The writer in me changed it to “first and forest,” and the phrase become our tagline.

It’s no coincidence I haven’t shaved my armpits or legs in months and months and months. That I’ve scarcely peed indoors since arriving here. That makeup and hair-brushing (hair-washing!) has seemed increasingly irrelevant. First you find the forest. Then you surrender to the forest. Finally you are the forest.

Forest I am, forest I be.

———————————————————————————————–

With November has come daylight savings time and freezing temperatures. The days are short and newly harsh. This land is almost abandoned, and I have not encountered another person on the beach in weeks. The stores and restaurants are mostly shuttered and locals feel newly licensed to speak their xenophobic truths. In short, my tenure here is drawing to a close. Yet I continue to write, and have finished a brutal, bright section I did not know this book needed when I first arrived.

Here I have had the space to find it.

On Thursday I went for a last walk in Bearberry Hill, my favorite spot in Truro. The entrance is opposite a site that once housed Thoreau, and the trail leads you past birch trees, mossy woods, cranberry bogs, and heart-stopping views before you slide down a big dune to Ballston Beach, where I’ve watched sunrises every morning.

As I’ve grown braver, I have explored more offshoots of this trail, and that day ventured further than I’d ever gone. After miles and miles, I ducked onto an overgrown path and, praying I wouldn’t forget my various twists and turns, kept going until I emerged at a very high clearing. Encircled by crimson trees and a thin line of ocean stood one very worn, very old bench. Wondering if it had been Thoreau’s, I sat down and bit into an apple from my pocket. Then I asked the sky, Will you show me where to go? and listened close.

thin line of ocean stood one very worn, very old bench. Wondering if it had been Thoreau’s, I sat down and bit into an apple from my pocket. Then I asked the sky, Will you show me where to go? and listened close.

In my question lay the answer.

A few hours later I slid triumphantly down the dune entrance to the beach. Covered in burrs and sand (ticks too, most likely), I ogled what stretched before me. The seaside colors had deepened into a dream palette: turquoise waves, cobalt sky, lilac horizon. Periwinkle crests, ivory sand. All of it eternal, ancient. Free.

The whole time here, I’ve been trying to formulate a prayer worthy of this sea. All my words have seemed like gimmicky affirmations, small potatoes.

That day, I finally figured out what to say. “I pray to be like you.”

I am fucking terrified about returning to Brooklyn—to a life that’s so much shabbier and more cluttered than I could see before. I’m afraid I won’t finish this book. I’m afraid I’ll sink back into dissociative despair. I’m afraid I won’t find the resources to fix everything that needs fixing.

But the world has changed, and me with it. While I’ve been away, the #metoo revolution has begun. Tuesday’s elections have suggested many Americans are finding their compass. I’ve written 50,000 words. The manic pixie dream boy has found a manic pixie dream girl, and in the sting of that discovery I have found oddly sweet relief. And I am no thinner but far more radiant. Months of farm food and good air and long hikes have strengthened my form. Gratitude has smoothed my edges. Love has filled my heart.

I have found oddly sweet relief. And I am no thinner but far more radiant. Months of farm food and good air and long hikes have strengthened my form. Gratitude has smoothed my edges. Love has filled my heart.

This is a phoenix-is-rising moment— a total post-traumatic growth opportunity—and I have new faith I’ll find my way. More than that, I know I won’t be alone as I do. Inside each of us shines a new sun as well as a dark forest. From sea to shining sea.